Judith Magyar Isaacson ’65, LL.D. ’94, dies at age 90

Educator, author, champion of equal opportunity for women, and a human-rights advocate whose passion was forged by her experiences in the Holocaust and by surviving the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Hessisch-Lichtenau concentration camps, Judith Magyar Isaacson ’65, LL.D. ’94, died on Nov. 10 at age 90.

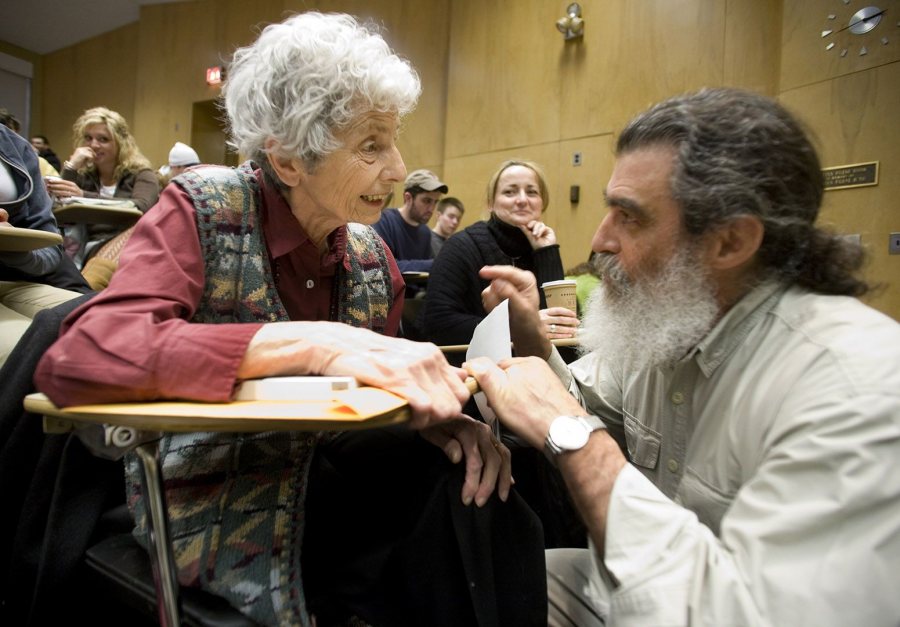

In 2006, Judith Magyar Isaacson ’65 signs her memoir “Seed of Sarah” after a class about the Holocaust taught by former Bates professor Steve Hochstadt. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics at Bates in 1965 and a master’s in mathematics at Bowdoin two years later. She taught math at Lewiston High School and then at Bates, where she became the dean of women in 1969 and dean of students in 1975. She retired in August 1978.

As dean, she was instrumental in ending the college’s unequal and antiquated codes of social conduct for men and women and in increasing extracurricular and athletic opportunities for female students.

In 1976, after discussing her Holocaust experiences with a group of students, Isaacson was moved to record those memories. Published in 1990, her memoir Seed of Sarah: Memoirs of a Survivor is an enduring inspiration of courage and resilience for young women and men.

‘Inextinguishable force of human worth’

Isaacson received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree at Commencement 1994, and the degree citation read, in part:

To remember vividly, so that none can forget — to say the unspeakable, so that all can hear — takes a voice of courage, power, and eloquence. Your strengths, Judith Isaacson, touch the lives of not only your family and your colleagues but those countless others who read in your personal and professional life the inextinguishable force of human worth.

For preserving, for giving testimony, for helping us to understand, and for the encouragement of conviction, we stand in admiration and resolve.

‘I fought pretty hard for women’

In 2004, Kirsten Terry Murphy ’07 wrote a story for The Bates Student about Isaacson’s induction into the Maine Women’s Hall of Fame.

Murphy wrote about Isaacson’s work as dean to dismantle the college’s notoriously unequal social rules that literally ran many pages for women and a few pages for men:

Isaacson could see that many of the codes of conduct at Bates were outdated, and quickly became an advocate for women’s rights at the school. She had children of her own in college at that point, and from their experiences she found that, comparatively, the policies at Bates were very different. “Young, 18-year-old women had far more freedoms at home than at Bates,” explained Isaacson….

Isaacson resolved other important complaints from students. One concerned the issue of parietals. Previously, men and women did not have permission to enter dorms of the opposite sex, but she changed campus-housing rules to allow visitations. Another problem surrounded sports. “I fought pretty hard for women to have athletic privileges,” she said.

Judith Isaacson talks with members of the Women’s Council in 1970, the start of changes that would make Bates social life more equal for women. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

‘How many times have I started anew?’

Isaacson retired from Bates in 1978. Shortly afterward, she wrote an essay about that final Commencement as dean of students and about her uncertain, but growing, idea of writing her memoirs, which would become Seed of Sarah.

The essay recalls the academic procession, led by President Hedley Reynolds, who

….carries his presidential paraphernalia with great dignity, his head held high, his steps springy. I am proud to be following just behind him, but still incredulous of my position. What right have I, the ultimate outsider, to be playing this venerable role?

My mind, that relentless time machine, projects a different image. Instead of stepping along the carpeted aisle in my academic gown, cap and hood, I see myself marching in a mile-long procession, at Auschwitz-Birkenau, stark naked….

This is my next-to-last official function at the College. After tomorrow’s Commencement, I’ll be embarking on a new venture, just like the seniors.

How many times have I started anew? I muse, as my eyes follow the members of the Class of 1977 making their solemn way to the front pews. How many different identities have I had?

Judit Magyar — a family name meaning Hungarian.

Jewish teenager under the Nazi regime.

Number 561.20578 in concentration camps.

Frau Hauptman, American captain’s wife in Germany.

Mrs. Irving Isaacson, lawyer’s wife in Lewiston, Maine.

Mom, to my children.

Judy, to my classmates.

Mrs. Isaacson, to my math students.

Dean Isaacson for the past eight years.

Will Grammi be next? Here is hoping.

Irving Isaacson ’36 and Judith Isaacson met after her liberation by American troops in 1945. Married on Dec. 24, 1945, they were photographed in 2000 by Phyllis Graber Jensen.

‘A warm and humorous optimist’

Historian Steve Hochstadt, a Holocaust scholar who taught at Bates from 1979 to 2006, had a long friendship with Isaacson that included a classroom relationship.

Each year that he taught his course on the Holocaust, she would visit.

“It’s very important for Holocaust students to meet a survivor,” said Hochstadt in 2006. “And Bates students get to see what kind of survivor Judith is: a warm and humorous optimist.”

Hochstadt tells the Portland Press Herald that Isaacson “was an extraordinarily joyous person who could tell you about very sad things that happened to her, her relatives and her friends, but who was able to retain joy in life.”

Hochstadt explains to the Sun Journal that Isaacson and Seed of Sarah expanded the narrative of the Holocaust to include women.

Speaking to 125 students in the Filene lecture hall, Hochstadt tells the Sun Journal, “she was so relaxed, so happy to be there, so confident.”

‘All who live, rejoice, rejoice’

Katalin Vecsey, a senior lecturer in the Bates theater department, was born in Hungary, as was Isaacson.

Isaacson, she said, became her “Hungarian mother in the United States.”

Seed of Sarah begins with this quote by a Hungarian poet, Endre Ady: “All who live, rejoice, rejoice.”

“I think that totally sums up her life,” Vecsey tells the Press Herald. “She really was so grateful to be alive and she shared that joy with everybody.”