Bates College’s distinctive Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance — in lieu of classes, a day of workshops and discussions with expert guests, all highlighted by a college gathering and keynote — owes much of its character to cataclysmic, yet coincident, world events 25 years ago.

That would be the beginning of the Persian Gulf War on Jan. 16, 1991, the U.S.’s first major armed conflict in a generation. Occurring in the world’s most volatile region, the outbreak of war rocked the Bates community in the days leading up to MLK Day, Jan. 21.

Students, particularly, were a mess.

Writing in The Bates Student, Steve Hochstadt, then a Bates history professor and, since 2006, professor of history at Illinois College, described a “depressed and disoriented” student body with an intense “hunger for information” (this was pre-Internet, remember).

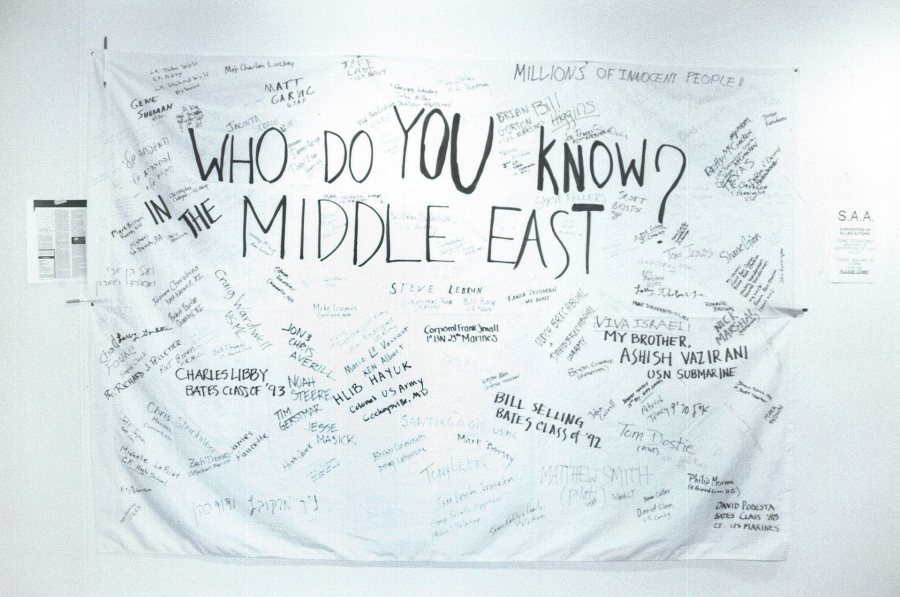

Following the start of the Persian Gulf War in January 1991, a sheet hangs, likely in Chase Hall, offering community members the chance to write the names of people they know in the Middle East. (Bates Communications)

The Bates faculty moved quickly to help students make sense of the chaos, a desire springing from their core mission as educators. “We felt we had the pulse of the student body,” Hochstadt wrote.

“As educators, we have a fundamental responsibility to continue educating,” said then-Dean of the College James Carignan ’61, who died in 2011.

Two key figures in the development of the college’s MLK Day tradition, Marcus Bruce ’77 (left) and James Reese, listen to the 2015 MLK Day keynote address. Bruce is the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies, and Reese is an associate dean of students. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In a special meeting on Jan. 18, the faculty voted to cancel classes on MLK Day, Monday, Jan. 21, “in honor of and to reflect upon Dr. King’s contributions to world peace, and to reflect upon the issues of peace and justice in the Middle East,” in the words of religion professor Marcus Bruce ’77.

Carl Benton Straub, then dean of the faculty, proposed an all-college convocation to begin the day’s programming. An ad-hoc faculty committee planned a series of events, discussions, and workshops, many of which would use Martin Luther King’s life and legacy as a means to understand the myriad issues at play.

Among the topics were “Is This a Just War?” “The Science and Technology of War,” and “The Mideast War and Jews in America.”

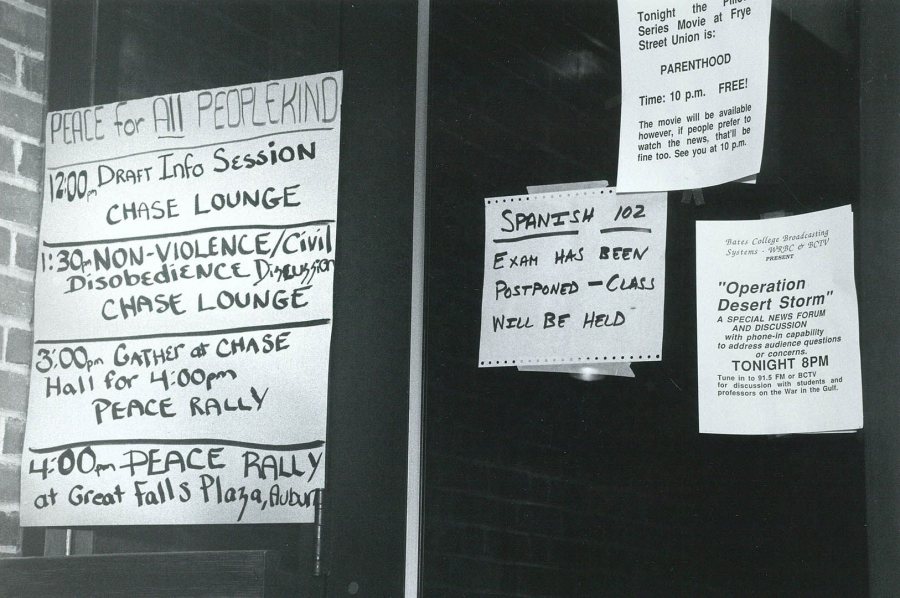

Flyers and messages during the Persian Gulf War hang, likely outside Ladd library, including one about the movie “Parenthood” being shown at Frye Street Union, noting that “if people prefer to watch the news, that’ll be fine too.” (Bates Communications)

Bruce is now the college’s Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies. As educators, he says today, “we are always engaging our students” in both the “practice and cultivation of freedom and conscience.”

Twenty-five years ago, he adds, the coincident timing of the Gulf War and MLK Day created the ultimate teachable moment, giving the Bates community the chance to reflect on “what it meant to practice freedom and conscience in that specific moment, to pause and allow students to breathe and consider their response to events.”

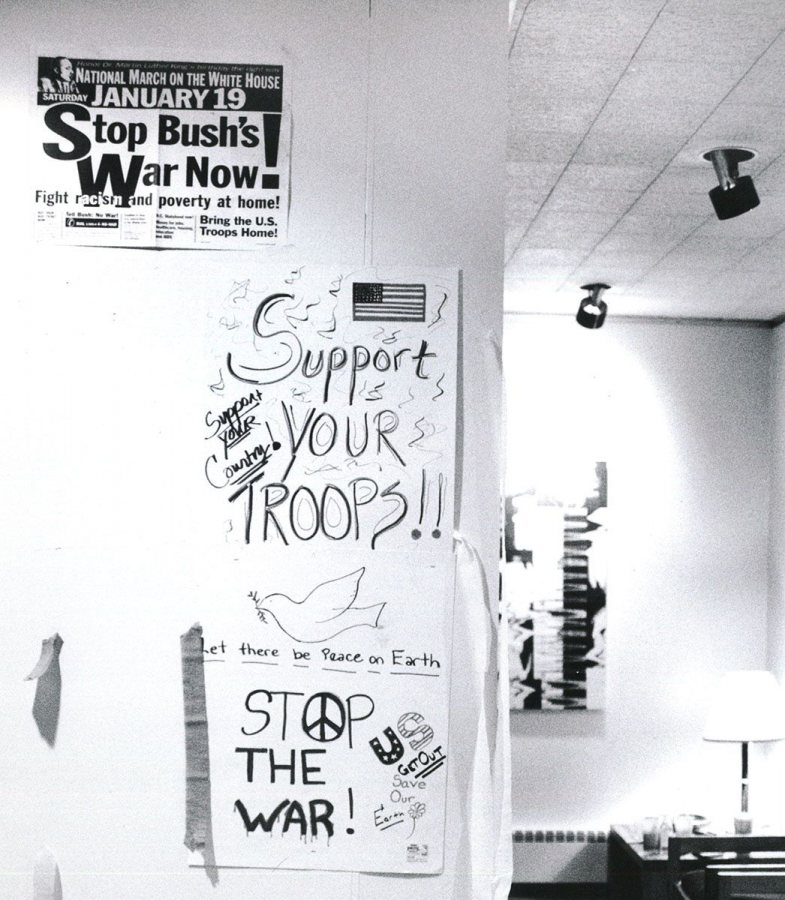

During the Persian Gulf War, the slogan “support the troops” emerged alongside anti-war messages, like these, likely in Chase Hall Gallery. (Bates Communications)

Donald Harward was in his second year as Bates president. In his first year, 1990, he had led Bates in elevating its MLK Day observance with a weeklong program called “Raise Every Voice.”

That program built on an already long tradition of MLK Day observances at Bates created in large part by Carignan and James Reese, then, as today, a dean in Student Affairs and an active member of the college’s MLK Day Planning Committee.

Recalling the events of 1991, Reese talks about the “ominous” feeling on campus in the days leading up to the war, and how the more politically minded students had asked their professors whether cancelling classes would be possible. “Their suggestions and the momentous momentum shown by the faculty were striking and memorable,” he says.

A peace protest passes by Chase Hall in the days following the start of the Persian Gulf War in January 1991. (Bates Communications)

In 1991, against the backdrop of the faculty’s nearly unprecedented vote to cancel classes, Harward opened the all-college convocation and set the tone both for that day and for many future observances of King’s birthday at Bates.

Extraordinary events affecting moral and political life, Harward said, demand equally exceptional responses.

“Not to pause and to assist student understanding of these events, their causes, and their implications, would, in the judgment of the faculty, be a failure to meet an extraordinary student need,” he said.

He added:

Seventy-five years ago, Benjamin E. Mays ’20 sat where you sit, his intellectual and moral resources shaped by his teachers and his colleagues here at Bates. His commitment to the cathedral of ideas, and the primacy of respect for human worth, were carried to his student, Martin Luther King Jr., whose own life and commitment we honor as a nation today.

In his articulation of the principles of nonviolence, Dr. King called for the development of the technologies of peace; he asked that its roots and causes be studied; he challenged us to work at making peace. Nonviolence, he argued, was the application of ethics to worldly politics….

“The easy, empty rhetoric of slogans and jingoism will not help.”

We are connected — teachers, students, Dr. Mays, Dr. King — and the realities that we must confront are connected — peace and war, justice and inequalities, human worth and human suffering.

Restructuring the educational events of this particular day, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, in the context of the realities of the Middle East is, in the judgment of the faculty, an educational opportunity which can make clear such connectedness….

[The topics discussed today] are consistent with the insistence that the context, the attitude, and the justification of our efforts be that the nature of this community is to be an arena for the examination and the conflict of ideas and values. The easy, empty rhetoric of slogans and jingoism will not help.

If there is a metaphor of healing and comfort within a community, the balm for that healing is that our connectedness is strengthened by attention to our individual, moral, and intellectual independence, and by the encouragement provided here.