MLK Day keynote: Acts of racial progress can ‘sow seeds of regression’

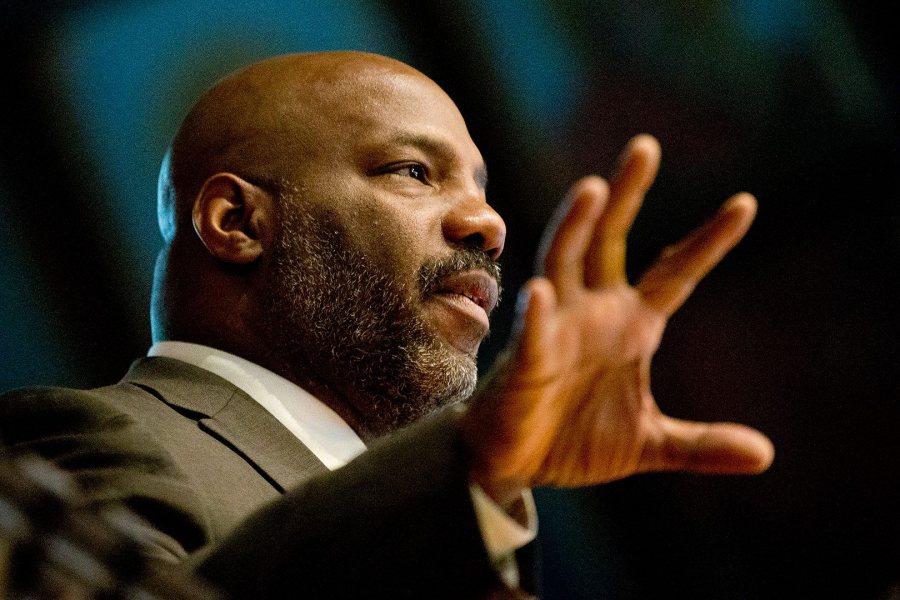

William Jelani Cobb gives the 2016 Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote address in the Gomes Chapel at Bates on Jan. 21. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

When 39 percent of white voters cast their ballots for an African American presidential candidate in 2008, people “thought it was a tremendous amount of racial progress,” historian William Jelani Cobb told a Bates College audience on Jan. 18, Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Barack Obama’s landmark victory was even deemed the start of a “post-racial” era in the U.S.

But, Cobb continued, “African Americans have been voting for candidates who did not share our race” for 135 years, since the 15th Amendment to the Constitution assured their right to vote. “And no one ever said, ‘Oh, African Americans are post-racial.’

“But when 40 percent of white people did, it was like, ‘OK, we’re done.'”

A staff writer for The New Yorker and a history professor and director of the Africana Studies Institute at the University of Connecticut, Cobb made that ironic point during his keynote address for Bates’ MLK Day observances.

Titled The Half-Life of Freedom, the talk was a trenchant argument for the centrality of race to our history — despite a prevailing view that race, as Cobb put it, is just “a side dish to the main course.”

Cobb’s talk came early in a packed schedule of MLK Day activities at Bates. Speaking to a near-capacity crowd in the Peter J. Gomes Chapel, Cobb shared the pulpit with U.S. Sen. Angus King, Bates President Clayton Spencer, and other members of the college community.

“If ever Martin Luther King Day were important for us as a day for community learning and reflection, it is now, in this moment,” Spencer said in her welcome. “And our topic today, ‘Mass Incarceration and Black Citizenship,’ could not be more timely.”

Elucidating the theme, she cited Michelle Alexander, whose book The New Jim Crow argues that the mass incarceration of young African American men is “simply the latest move in a highly adaptive system of racial exclusion that extends back to the earliest history of the nation.”

In an era when race has ostensibly ceased to be a basis for the denial of rights, “instead, we target people of color, label them as criminals, and then feel justified in pushing them, systematically and irrevocably, to the margins of society,” Spencer said.

High-profile instances of police violence against blacks and of prejudice on campuses from Yale to the University of Missouri have been a wake-up call. “These past two years, in particular, have been a time when many of us who like to think of ourselves as progressive on issues of race have gone to school on the question of structural racism,” Spencer said, “and how it continues to manifest itself in systematic, insidious, and relentless ways.

Sen. King offered a tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. that linked the Battle of Gettysburg and the 1963 March on Washington (which Angus King, then a college sophomore, observed from the vantage point of a tree near the Lincoln Memorial).

In linking the 1963 march and the 1863 battle, King quoted Joshua Chamberlain, whose leadership of Maine troops at Little Round Top was decisive. “Generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field to ponder and dream; and lo, the shadow of a mighty presence will wrap them in its bosom and the power of the vision shall pass into their souls.”

Associate Professor of History Joseph Hall introduced Cobb. “Read some of his work,” Hall urged the crowd. “Dr. Cobb explores how the phenomena of a moment have pedigrees that are decades or even centuries old.”

Cobb took a metaphor from Thomas Levenson’s recent history The Hunt for Vulcan, the story of how the traditional Newtonian view of physics was disrupted by the advent of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. There were discrepancies in the motions of celestial bodies, Cobb said, that Newton’s laws couldn’t explain but Einstein’s theory could.

According to Einstein, phenomena like gravity and time “are all relative, and we can only understand the existence of one body by understanding its relationship to another.”

So it is with the perception and the reality of the American political system. That system, Cobb explained, is traditionally seen as a historic break from millennia of tyranny, a realization “of the Enlightenment idea that all humans are educable, that they have equality, that they’re born with inherent inalienable rights.”

But, as with Newton’s vs. Einstein’s physics, there are phenomena in American history and culture that this idealistic view can’t explain. “You wind up with those same kinds of nagging inconsistencies that people experienced,” said Cobb, “as they were trying to apply Newton’s ideas to the celestial motion of bodies in the universe.

Visiting speaker William Jelani Cobb, at left, meets Evan Molinari ’16 of Milwaukie, Ore., who told Cobb about his senior honors history thesis on Paul Robeson and Jackie Robinson. In the background is Rakiya Mohamed ’18 of Auburn, Maine. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“And so race has deformed democracy in the same ways that gravity deforms space and time. And unless we understand individuals in relation to other individuals, we cannot understand the way that our society operates today.”

While many would like to believe that race is “a side dish to the main course of American history,” it’s really central to that history, even embedded in a Constitution that assigned each African American man three-fifths the value of a white man.

In one especially sobering example, Cobb mentioned how an early draft of the Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson, deplored the Crown’s involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade — but that condemnation was expunged from the final draft to placate slaveholders in the South.

Cobb drew a gasp from the audience when he continued, “Every Fourth of July, as we recognize the nation’s independence, we also recognize the anniversary of black humanity being copy-edited out of the final document.”

“When we look at the history of states, race confronts us everywhere,” Cobb continued — from Florida, seized by Andrew Jackson from the Spanish so that escaped slaves from the United States couldn’t take refuge there, to Maine, admitted to the Union as a free state to counterbalance adding the slave state of Missouri.

And remember the Alamo: Settlers seized Texas from Mexico in part because the Mexicans, who were offering free land to white farmers, prohibited slavery.

Homing in on Bates’ theme for the holiday, Cobb presented some of his most important revelations, involving two of the amendments to the Constitution that were passed after the Civil War to redress injustices embedded in the original document.

Jelani Cobb addresses a near-capacity Gomes Chapel on Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2016. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

“Sometimes,” he said, “within actual progress there are the seeds of regression.” For example, the 13th Amendment eradicated slavery — “except for individuals duly convicted of a crime,” Cobb explained.

“So it is no coincidence that in the wake of Emancipation, Southern economies began to rely increasingly on the labors of people who were incarcerated,” he said. “The legacy is very clear.

“We can see in places like Parchman Farm, in Mississippi, which started out as a slave plantation and then became a prison. There were people who lived on Parchman Farm as slaves, were emancipated, and then came back to Parchman Farm as prisoners.”

Cobb devoted a few minutes to Maine Gov. Paul LePage’s Jan. 6 racially charged comments about the nicknames and dating behavior of people who come to Maine to sell drugs — specifically, the remark that “half the time [dealers] impregnate a young white girl before they leave.”

LePage, said Cobb, “echoed an idea that is tremendously dangerous in American history, and that is that we have to protect white women from the menace of black men.” How dangerous? Dylann Roof, a white man accused of shooting nine African Americans to death in a South Carolina church last June, cited the need to protect white women from black men among his motivations.

Cobb said, “We should be disturbed by the fact that these ideas share the same provenance, that they come from the same place. We should be concerned about what these ideas have been used to justify.”