Facts, firsts, and fictions from 150 (or more?) Commencements

The first Bates Commencement was in 1867, which makes the 2016 edition the 150th in college history. Or have there been more?

In the spirit of trying to make things count, here are 15-plus facts and stories from Bates Commencements.

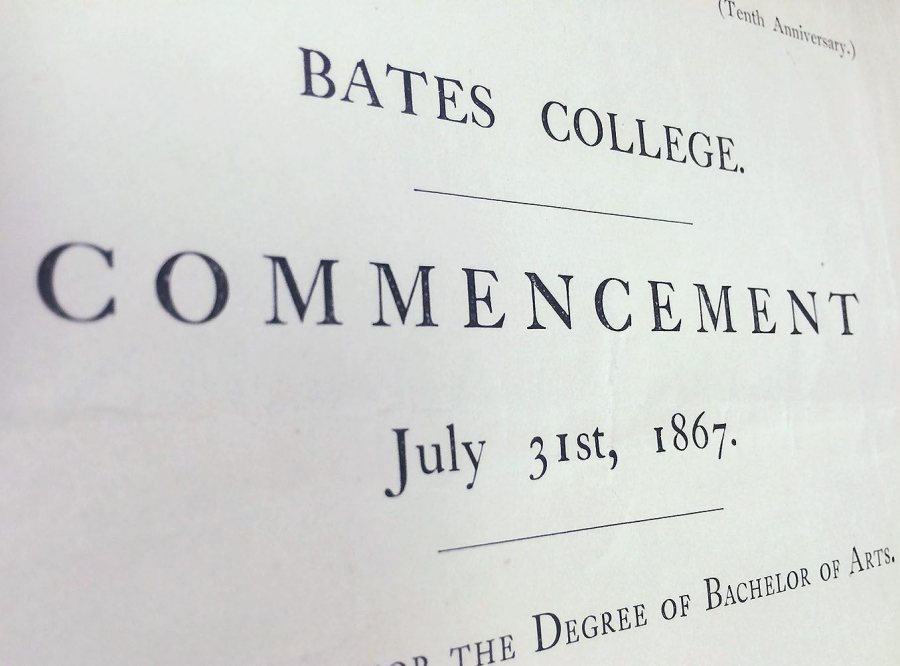

The first Commencement was on July 31, 1867

A detail of the cover of first Bates Commencement program, in 1867. The words “Tenth Anniversary” at upper right allude to the September 1857 opening of the Maine State Seminary, which became Bates. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Eight students received bachelor’s degrees at the first Bates Commencement, which was held at a Baptist church on Main Street in Lewiston.

Frank Sleeper, a senior from Lewiston, was the first speaker, delivering the Latin Salutatory, a graduation tradition of the day that Bates adopted for its ceremony.

The program titles his address Disquisitio Salutatoria, which “we could translate very loosely as ‘Opening Remarks,'” rather than ‘Address of Greeting,'” says Tom Hayward, lecturer emeritus in classical and medieval studies.

“You have labored to found a college which shall be an ornament to our state.”

Delivering his salutatory in the required Latin, Sleeper praised Bates president and founder Oren Cheney.

“Joyful indeed to you must be the day which brings to you the fruits of years of patient toil and sacrifice,” Sleeper said. “The faithfulness with which you have labored to found a college which shall be an ornament to our state is known to all, and as long as this institution shall exist so long will your name be remembered with blessings and honor.”

A featured Commencement speaker is a post-World War II phenomenon

Before World War II, the featured speakers at Commencement were students. The 1936 slate features talks on “The Juvenile Court,” “The Novelist Sits in Judgment,” “Creative Thought,” and “Stability in China.”

During the war, Bates was on an accelerated academic calendar so would confer some degrees at special convocations in fall and winter. Featured guests spoke at those gatherings, including Joseph Drew, the diplomat who had been interned by the Japanese at the start of the war, in January 1943.

The custom of having a featured speaker then took hold and has been a staple of Commencements in 1944.

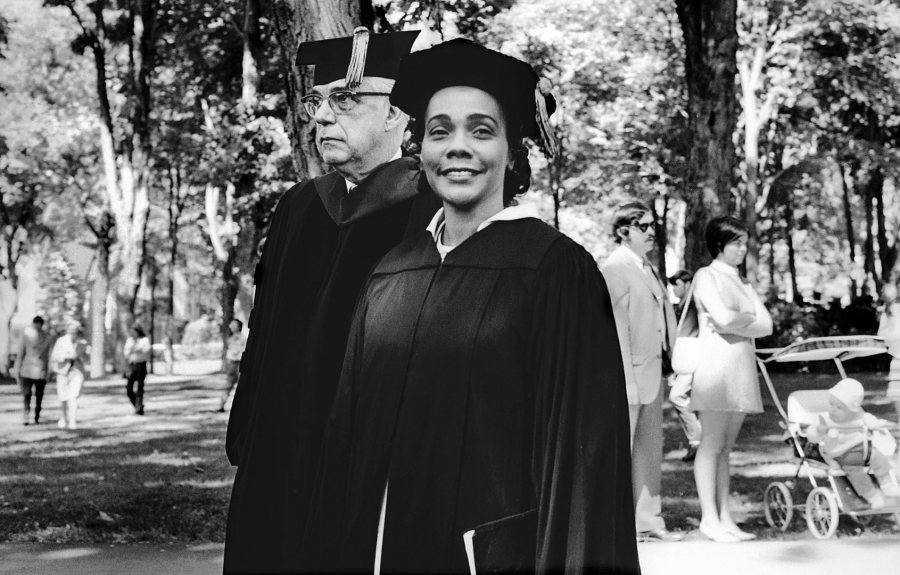

The first African American speaker at Commencement was Coretta Scott King

In her 1971 address, Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King Jr., assassinated three years before, delivered a blistering attack on violence, racism, and more in America.

She took on one of the most controversial issues of that year, the arrest and pending trial of activist Angela Davis on weapons charges.

Coretta Scott King marches in the 1971 academic procession at Commencement. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“While I sharply disagree with the politics of Miss Davis, I must say that if her blackness, her politics, and her womanhood are being judged, and not the crime, then all Americans will lose some of their liberties along with her.”

She also paid tribute to Benjamin Mays, Class of 1920.

“From the earliest days of the Struggle, until my husband’s last rites on the campus of Martin’s beloved Morehouse, Dr. Mays was at our side. The friendship, which he and my husband formed when Martin was a Morehouse student, grew, deepened, and ripened with the years….

“So I am happy this morning to be present at the alma mater of my friend and colleague. My happiness is doubled when I realize that in 1917, a period rife with the inherent inferiority of the black man and the inherent superiority of the white man, Bates College accepted a young black man from South Carolina and allowed that young man to emancipate himself and accept with dignity his own worth as a free man.

“I make bold to state that Dr. Mays is without a contemporary peer in the inspiration and motivation that he has given to thousands of young blacks, men in particular, in their quest for emancipation from the myths of racism.”

The first female graduate was Mary Wheelwright Mitchell, in 1869

Bates graduated its first woman, Mary Wheelwright Mitchell, at its third Commencement, in 1869. She was a determined student. Offered a scholarship, Mitchell turned it down: “I can take care of myself.”

While six women started as members of Bates’ first college class, none graduated until Mitchell, a fact that reflects how difficult it was for Bates founder Oren Cheney to turn radical theory into sustainable practice, as Tim Larson ’05 wrote in his honors thesis, “Faith by Their Works.”

Larson notes that Cheney “obviously saw Bates as a pioneer in breaking gender barriers in the field of higher education.”

Cheney also “accurately foresaw the future of American higher education in predicting that ‘all the colleges of our country will welcome women.’ This was a bold assertion to make when Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Dartmouth, Williams, Tufts, and all the other New England colleges were still closed to women.”

Nevertheless, Larson writes, the first female students “obviously faced prejudices, from their male counterparts and society in general,” that may have contributed to their leaving the college before graduation.

In the end, “despite hostility and some well-meaning paternalism by certain individuals, Bates was among the more progressive institutions in admitting women alongside men, when many other colleges refused to do so for another century.”

Years later, Bates granted degrees to two of the women, Francena Stanton Morrell and Sybil Chase Ballard: Morrell in 1931 and Ballard in 1932. Here’s a clip of Ballard, age 87, at Commencement 1934:

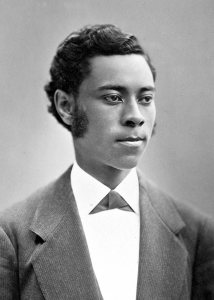

The first African American graduate was Henry Wilkins Chandler, in 1874

Henry Chandler, Class of 1874, was the college’s first African American graduate. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“The abolitionist ideals of Bates’ founder, Oren Cheney…were largely acted out as he recruited the earliest African American students for the school,” writes Larson in his honors thesis noted above.

Cheney’s recruitment included Henry Chandler, the first African American graduate of Bates, in 1874.

While six of the first nine African American students to attend Bates were former slaves, most recruited by founder Oren Cheney during and after the Civil War, Chandler was born free.

Ten years before Chandler’s graduation, Cheney had written in his diary about stopping in Bath, Maine, to see an African American acquaintance. Cheney recorded that the man’s “son and daughter will ‘go through’ the college.” That son was most likely Chandler.

After graduating from Bates in 1874, he studied law at Howard University, then practiced law in Florida; he also edited The Ocala Republican and The Plain Dealer newspapers.

In 1880, Chandler was elected to the Florida state senate and held office for two terms. He was also a state delegate to the Republican National Conventions.

Commencement and Reunion used to take place on the same weekend

The tradition of welcoming alumni back for Commencement had been formalized by the late 1890s, and by the 1930s, these class gatherings were their own thing.

And a big thing, as alumni built out the event known today as Reunion with dinners, class outings, presentations, and, of course, the popular Alumni Parade.

Long held during the same weekend, Commencement and Reunion were split around 1980.

Here’s the Class of 1914’s “Round Up” at the 1934 Alumni Parade at Commencement.

The U.S. Navy was part of the awarding of degrees during World War II

During World War II, Bates was on a 12-month schedule, and undergraduates could choose an accelerated program, so diplomas were awarded a few times a year (three times in 1943).

Also during the war, the Navy had 120,000 student sailors stationed at 131 U.S. colleges, including Bates, for officer training and accelerated college instruction.

In this clip, the sailors of the Bates V-12 program lead the way to the Oct. 24, 1943, convocation, where 13 students received bachelor’s degrees.

A Senior Speaker returned to Commencement in 2013

While student speakers were long the norm at Baccalaureate, the day before Commencement, students had not had a featured speaking role at graduation since the mid-1900s.

That changed in 2013 when Tommy Holmberg ’13 became the first Senior Speaker in the modern era.

The Commencement Concert was the “big event of the season” in the 1870s

Opera singer Madame Nordica, seen here in an undated photo, sang at the 1877 Commencement Concert. (George Grantham Bain Collection / Library of Congress Prints and Photographs)

In its early years, Bates “concentrated its musical efforts on the commencement concerts,” said the Lewiston Evening Journal in 1939, and the concerts became “the big musical and social event of the season for the Twin Cities.”

Some of the concerts were held at the new Music Hall on upper Lisbon Street, “the best opera house east of Boston,” according to one account. It’s now home to the district court.

By the mid 1870s, a Bates Commencement Concert could cost upwards of $1,200, the equivalent of about $21,000 today.

The 1877 concert brought “two of the most famous singers that New England has ever given the world,” according to the Journal.

One was opera singer Annie Louise Cary, a native of Wayne, Maine.

George Loring White, an 1876 graduate, recalled that “when Miss Cary sang ‘Coming thru the rye,’ smiles became distinctly audible all over the house. I felt like coming thru the rye myself.”

The second singer at that 1877 concert was the even more famous Lillian Norton, a native of Farmington, Maine, who would gain worldwide recognition as “Madame Nordica.”

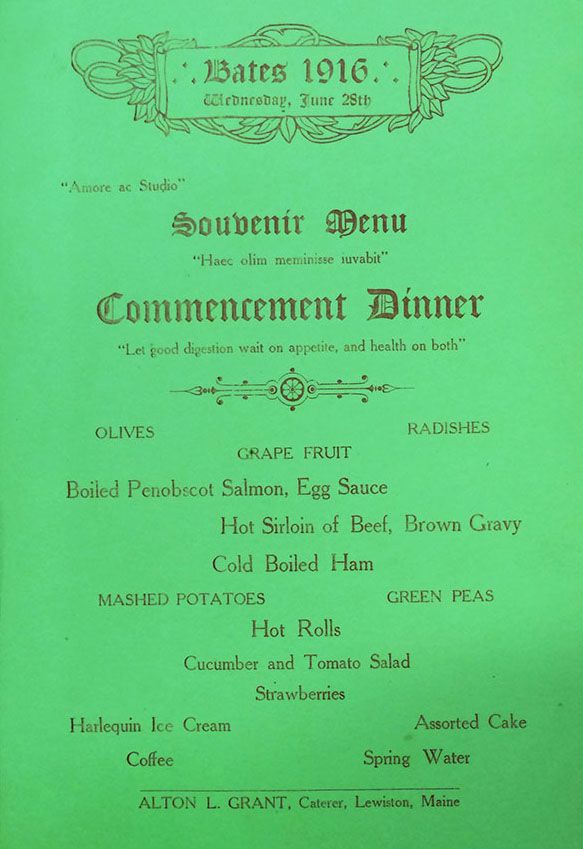

The Commencement Dinner was once catered by a well-known local name

In the early 1900s, the Commencement “Dinner” was not in the evening but right after graduation, at noon. This is the older use of the word, in the sense of the main meal of the day.

Note that the 1916 menu was catered by “Alton L. Grant.” His business became Grant & Grant Caterers, which became Grant’s Bakery on Sabattus Street, the go-to spot for parents sending sweets to their students.

Here’s a peek at this year’s spread, now known as the Commencement Luncheon:

- Summer slaw salad with lemon vinaigrette

- Cavatappi salad with sundried tomato basil and fresh spinach

- Edamame hummus with tortilla chips

- Lobster salad rolls

- Chicken salad rolls

- Olive oil and garlic roasted vegetable medley with portobello mushrooms, summer squash, and zucchini

- Sliced watermelon

- Cookies and brownies

- Italian ice

- Assorted beverages, including Summit Springs Water

The 2016 edition is actually the college’s 153rd Commencement

Strange, but true. In the mid-1960s, President Charles Phillips implemented an aggressive three-year graduation option. To make it work, he created a third academic term, which became Short Term.

By spring 1968, the first cohort of three-year grads was ready to graduate. On April 22, the college held a Commencement for its traditional four-year cohort. Then the three-year group graduated on June 28, after they had finished their final Short Term.

The same was true in 1969 (April 28 and July 4) and 1970 (April 20 and June 12).

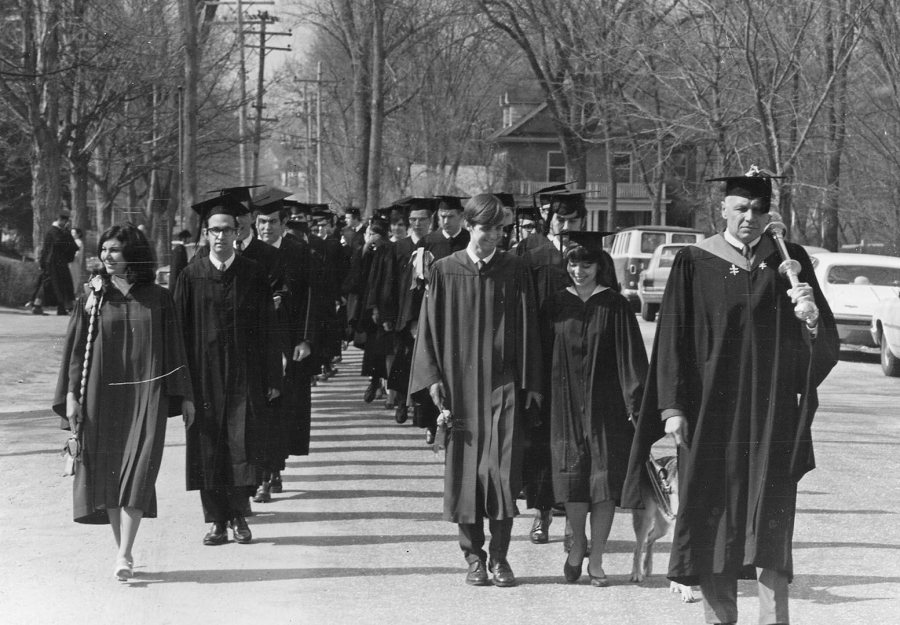

The academic procession in April 1969 for the first of two Commencements that year. This one was for four-year graduates; the second, for three-year grads, was on July 4. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

So unusual was the setup that when Bates, under President Hedley Reynolds, returned to a single-Commencement format in 1971, it was hailed by the Lewiston Sun Journal in its lead editorial. “The change is preferable to the confusing, double Commencements” of the past several years.

There have been seven locations for Bates Commencements

Until the Chapel was built in 1914, Bates held Commencements downtown at a Baptist church at the corner of Bates Street and Main Street, near where the venerable Sam’s Italian Restaurant is.

Here are all the venues:

- 1867 to 1913: Baptist church on Main Street (except in 1876)

- 1876: Lewiston City Hall

- 1914 to 1948: Gomes Chapel

- 1949 to 1966: Lewiston Armory on Central Street

- 1967: Alumni Gym

- 1968: Alumni Gym and Chapel

- 1969: Alumni Gym and Chapel

- 1970: Alumni Gym

- 1971 onward: Historic Quad in front of Coram Library (rain site: Merrill Gymnasium)

The first outdoor Commencement was in 1971

Alumni Gym was to be the site of the 1971 event, but lore tells us that students asked President Reynolds if it could be moved outdoors.

His assent is about the best “yes” a president has ever made.

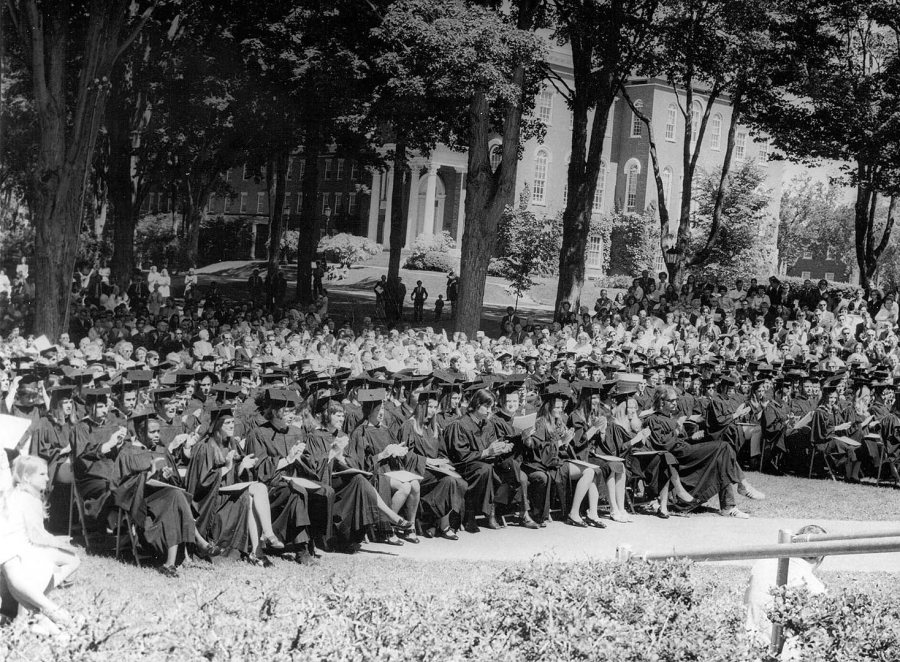

A scene from the first outdoor Bates Commencement, in 1971. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

In 1989, the late Peter Gomes ’65 praised the Bates Commencement tradition that had evolved under Reynolds. “When I took my degree, in 1965, [Commencement] was in the overheated and underventilated Lewiston Armory, a day or two after the circus had come and gone,” wrote Gomes.

Then came 1971, the start of the modern Commencement tradition, with the “bucolic setting of the Coram Quadrangle, the Portland Brass, the piper and the procession, and most of all the elegant austerity of the ceremony itself,” Gomes wrote.

“There is neither a wasted word nor gesture on Commencement Day. It is rich in its austerity….”

The Coram “stage” also used to host a Commencement play

In chronicling its design by New York City architects who had shaped the Broadway theater district, Phillips Professor of Art and Visual Culture Rebecca Corrie noted, “Is it any wonder that the facade of Coram has become such a perfect stage for the College’s most public and important ceremonies?”

For many years, the student theater group put on a Greek play as part of Commencement Weekend.

This clip shows the 1934 performance of Aristophanes’ The Birds, staged by the 4-A Players (now The Robinson Players). The play was chosen as part of that year’s celebration of the centennial of Jonathan Stanton, famed professor and ornithologist.

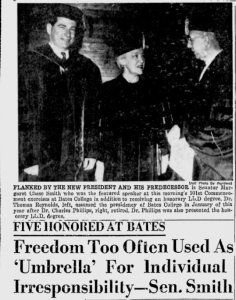

The first female Commencement speaker was U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith

In this clipping from the Lewiston Daily Sun, U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith is flanked by new Bates president Hedley Reynolds (left) and President Emeritus Charles Phillips at Commencement 1967.

U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith of Maine talked about pragmatism in her 1967 address, the first by a woman.

She defined pragmatism as exercising personal freedom without being responsible to society.

“There are two sides to this glorified modern pragmatism,” Smith said. One is the attitude that “I’ll get mine in whatever way I can,” while the other is “the creed of ‘not getting involved.'”

She concluded, “If our nation is to maintain the moral fibre that is necessary to the survival of our way of life, then we must reject the glorified pragmatists who advocate cutting corners, who preach the propaganda of expecting ‘something for nothing,’ who espouse the doctrine that the ‘end justifies the means,’ and who caution against ‘getting involved on matters of principle.'”

The mace joined the academic procession in 1949

As the senior member of the faculty, Phillips Professor of Economics Michael Murray will lead the 2016 Commencement academic procession.

At Commencement 1949, Professor of Biology William Sawyer, Class of 1913, holds newly given mace as its creator, Leverett Cutten, Class of 1904, and President Charles Phillips look on. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

The mace symbolizes academic authority — an understandable connection, since ancient warriors used maces to bash their foes. The Bates mace was fashioned by Leverett Cutten of the Class of 1904 and given to the college in 1949.

While many maces are topped with a crown, Cutten wanted his design to leave “no doubt about Bates College’s being in the state of Maine,” as he said in 1949, so he fabricated pine cones and tassels to form an arch to support the garnet that sits at the top.