‘Here be Bates’: A history lab puts the college on the map

Visiting Assistant Professor of History Katherine McDonough, left, and members of her “Innovations in Mapping” class conduct a triangulation exercise on the Historic Quad on May 6, 2016. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Justin Hoden ’18 has an important role to play in a class exercise — but he doesn’t know whether he’s still playing it.

His classmates are hundreds of feet away on the steps of Hathorn Hall, working with a surveyor’s compass, notebooks, pencils, and a high wooden table, called a plane table, covered with a sheet of paper.

Hoden of Bryn Mawr, Pa., has been assigned to stand at the edge of the Historic Quad near Campus Avenue and display what looks like a glorified yardstick. Which he’s been doing for a while, with no communication from the classmates.

As a huddle at the plane table starts to drag on, Hoden deserts his post and skateboards back to Hathorn and the group. It turns out that his classmates have indeed gotten the angle measurement they need, training the compass on Hoden and the stick — a surveying instrument called a stadia rod.

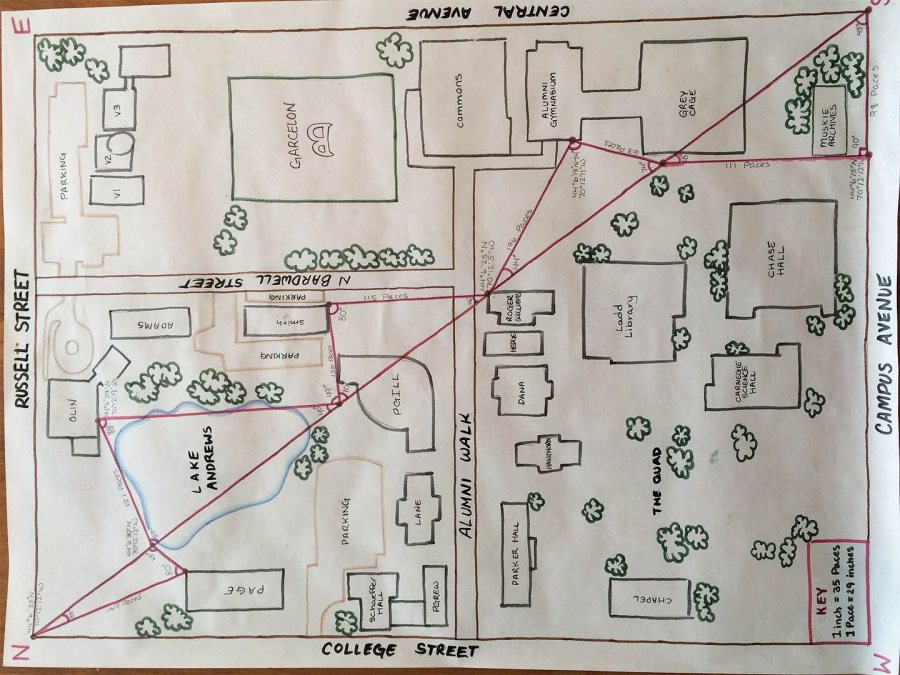

Triangulation in action: A map of the so-called Bates block by students in the Short Term course “Innovations in Mapping: From Paper to Pixels.”

“I had no idea they were done,” Hoden tells Katie McDonough, visiting assistant professor of history and leader of the Short Term course the students are taking. “How would you communicate with the other stations?”

Translation: How would 18th-century French mapmakers in the field have communicated over long distances? (They would have signaled with mirrors or fires, among other methods.) Hoden’s question exemplifies one of McDonough’s goals for the course, “Innovations in Mapping: From Paper to Pixels.”

The course looks at two eras when science enabled great leaps forward in mapmaking and navigation: the 1700s, specifically in France, and the last few decades up to the present day. And McDonough is making sure that her students are not only reading about mapmaking techniques: They’re practicing them, too.

!["The whole idea of using these ancient [mapmaking] methods is really interesting to me," said Justin Hoden '18, an avid sailor from Bryn Mawr, Pa. Hoden is holding a stadia rod, and Visiting Assistant Professor of History Katherine McDonough is in the background. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2016/05/160506_History_Mapping_0076-600x900.jpg)

“The whole idea of using these ancient [mapmaking] methods is really interesting to me,” says Justin Hoden ’18, an avid sailor from Bryn Mawr, Pa. Hoden is holding a stadia rod, and Visiting Assistant Professor of History Katherine McDonough is in the background.

(Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“This class is designed around recreating historical experiences as a learning device, a learning opportunity,” she says. “They’ll gain an understanding of what mapmaking was like, and some of the challenges,” like being abandoned on the edge of campus holding a conspicuous stadia rod.

“As far as I know, no one has done this with mapping.”

It’s easy to see why McDonough wants her students to know more about contemporary mapping technology. For myriad reasons, “the transition to digital mapping, and what that means for how we engage with maps as individuals or as societies, is really important,” she says.

“Where does the geographical information for Google Maps come from? What are we doing with it? And of course, then there are questions about the politics, the economics, and the cultural issues about how we’re using that information.” (To say nothing of the cognitive effects.)

But why 18th-century France? At that time, “France was the first country to do a systematic national survey based on geodetic science — that is, not just based on plane geometry but on knowledge of the size and shape of the Earth, which is a question they were grappling with at that time,” McDonough explains.

“It’s this interesting moment when mapping is very much becoming scientific, self-consciously so, which I think is a nice corollary to a lot of GIS” — geographic information science.

By comparing these two periods, she says, “one of the big questions we can think about is, Where does geographic information come from? And in the 18th century, it comes from fieldwork plus calculation.

“The French national survey is exciting because it’s one of the first surveys that combines topographical exploration of a real landscape — the kingdom of France — with groundbreaking mathematics on the size of the Earth.”

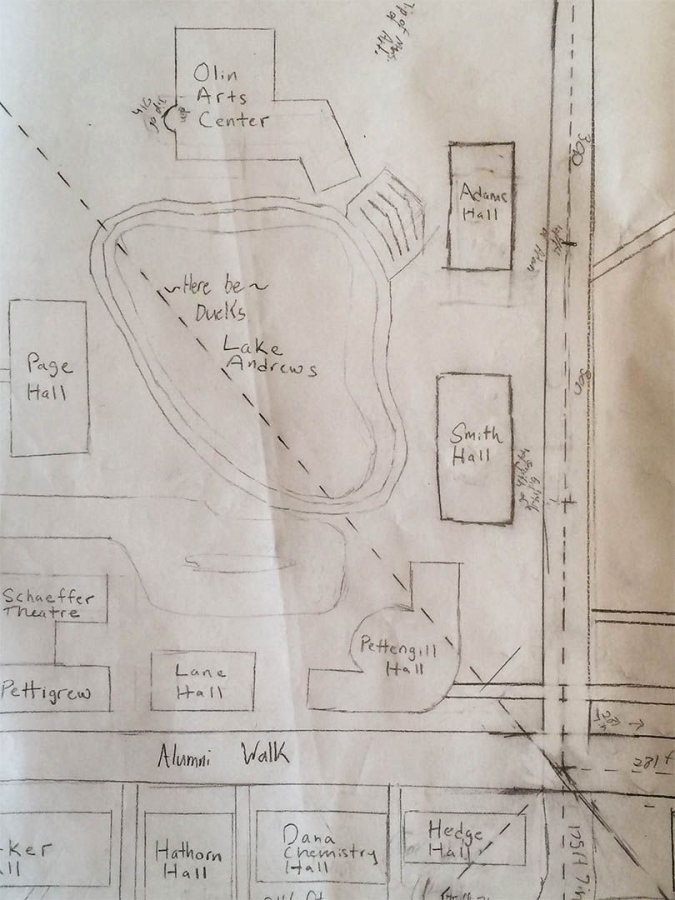

“Here be ducks”: Note the warning in this detail from a map of the Bates campus by students in the course “Innovations in Mapping: From Paper to Pixels.”

Labs in history courses are rare, but it was an “Innovations in Mapmaking” lab that brought the student surveyors onto the Quad on a sunny May 6.

They were assigned to learn a process called triangulation. It’s a term whose meaning can shift according to context (the political definition is especially fraught); but in mapmaking and surveying, it refers to the mathematical manipulation of triangles to create representations of a landscape.

The first thing the students did was measure the distance from the corner of Campus Avenue and College Street to Hathorn Hall. If you know the length of one side of a triangle and the values of its angles, you can use trigonometry to calculate the lengths of the other sides. That way you can plot out a triangle on a given piece of land, like the kingdom of France or the campus of Bates, and transfer it to your map.

Then, using a side of your first triangle as the base for a new one, and so on, you can use this process to subdivide the land into a chain of abutting triangles. The Innovations students divided the “Bates block,” the central section of campus bounded by four Lewiston streets, into four triangles, drawing diagonals from street corner to street corner.

Finally, the placement of triangles in relation to known latitude and longitude positions also enables the mapmaker to plot the locations of landmarks and situate them on the map. McDonough left it to her students to decide which landmarks to incorporate.

In fact, after providing technical instructions and setting goals, she left much of the decision-making to them as they proceeded. “The lab exercises in this course are different from what students might be used to in science labs,” she explains.

“I provide the students with a historical scenario, objectives, and basic methods. They recreate historical practices to work out the details of the methodology, collect data, and reflect on how this experience can impact our understanding of the past.”

It says something about the previous pace of technology that, to teach 18-century mapmaking techniques, McDonough was pleased to borrow mid-20th-century equipment, now retired, from the geology department. (Still, her students did use GPS on their cellphones to double-check their work, and McDonough also bought 300-foot DeWalt tape measures because historically accurate measuring chains are too expensive — “another 18th-century annoyance,” she says.)

A member of the “Innovations in Mapping” class, Haley Crim ’19 of Sandy Spring, Md., uses a surveyor’s compass to determine an angle during a triangulation exercise on May 6, 2016. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Tapping her own research into 18th-century French mapmaking, she created the mapping course for Bates. It has incorporated field trips (the Osher Map Library at the University of Southern Map being a standout), multiple opportunities to meet professionals in the field, and diverse lab projects, including support for energy-monitoring and waste-stream improvement projects undertaken by Bates’ sustainability manager, Tom Twist.

McDonough, who’s nearing the end of her yearlong Bates appointment, doubts she could put the course together at another institution. “I’ve never had this flexible format like Short Term,” she says.

With the course cross-listed in environmental studies, McDonough has been impressed by “the number of Bates students who are interested in environmental studies — and in environmental humanities,” she adds. “It’s been very exciting to work with a student population who has those interests, and I think that’s unique to Bates in some ways.”