“In the streets of Havana, I was able to feel that something was changing so rapidly,” says composer Hiroya Miura, who was a featured guest at a music festival in Cuba in November.

Against the long-advertised backdrop of totalitarian rule, cultural suppression, and economic deprivation, Miura also found a lively arts scene, a musical community hungry for fresh ideas — and, he says, a surprising optimism. The Cubans he met, he says, “seem so positive. They always have a way of spinning everything in a positive light.”

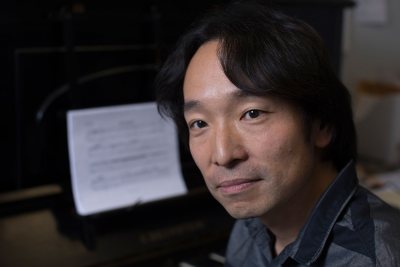

Hiroya Miura, associate professor of music st Bates, is shown in his Olin Arts Center office shortly before he attended a contemporary-music festival in Cuba. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

It was a momentous time to visit the island. Miura flew to Havana just five days after the November elections that cast doubt upon, among other things, the thaw in U.S.–Cuban relations that President Barack Obama helped bring about.

“Then six days after I came back,” Miura says, “Fidel Castro died.”

The occasion for Miura’s visit was the 29th annual Festival de Música Contemporánea de La Habana (Havana Contemporary Music Festival). He was one of four U.S.-based composers invited to the nine-day event as part of an artist delegation representing the American Composers Forum, an advocacy organization. It was just the second year that the ACF participated.

Also in the delegation was the New York City quintet Third Sound, which performed a concert of music by the four composers — Lembit Beecher, Pierre Lambert, and Wang Lu, in addition to Miura, who is an associate professor of music at Bates and conductor of the college orchestra.

The festival was a performance tour de force, with dozens of musicians offering two, sometimes three, concerts a day. Also on the program were panels, including one in which the ACF composers and two other musical groups from the U.S. advised young Cuban musicians on making things happen.

“Castro had very strict cultural policies, and for Cubans, contemporary music kind of stops around 1960–65,” Miura says. “So they are very eager to learn.

“I brought my CDs and scores, and you could really see their eyes light up, seeing these new pieces by living composers from here. During one of the workshops, we heard a demonstration by a new improvisation ensemble of young Cuban composers, and their sincerity for the exploration of new sound was quite moving.”

Hiroya Miura consults with Third Sound pianist Orion Weiss as four members of the ensemble rehearse Miura’s “Open Passage” in Havana. Also shown are flutist Sooyun Kim and cellist Michael Nicolas; out of the frame is violinist Adda Kridler. (Courtesy of Hiroya Miura)

The Miura work that Third Sound played at the festival’s Nov. 18 ACF concert was “Open Passage — In memoriam Andrew Svoboda.” Written in 2005 for alto flute, violin, cello, and piano, the piece is a tribute to a lost friend.

“He was a very young talented composer, and he just died all of a sudden of cardiac arrest at the age of 26,” says Miura. “It was a very emotional piece for me.

“Considering that writing and hearing the piece was a way of remembering my friend, and his father was a political dissident from communist Czechoslovakia in the 1960s, hearing the piece 10 years later in Havana felt strangely fitting.”

Miura adds, “My friend’s last name, Svoboda, means ‘freedom’ in Czech.”

From left: Patrick Castillo, composer and director of Third Sound; composers Wang Lu, Pierre Jalbert, Hiroya Miura, Tania León, and Lembit Beecher; International Contemporary Ensemble representatives Alice Teyssier and Ryan Muncy. León performed in her native Cuba for the first time in nearly 50 years at the festival. (Courtesy of Hiroya Miura)

A high point of Miura’s visit was the Fábrica de Arte Cubano — the Cuban Art Factory. Installed in a former power plant and olive oil factory, the F.A.C. is a sort of one-stop shop for hip-and-cool culture — music, dance, art, and more.

“It’s extremely vibrant, there are lots of young people, they stay open until like 3 in the morning, and they have live music playing throughout the night,” he explains.

“On multiple levels of galleries, dance floors, and bars, I was amazed by the people’s energy and free-spiritedness. These alternative and independent art and music scenes seemed to be starting as a hybrid between a state-run facility and private business in Havana — which is an incredible development considering the strict policies the government used to have.”

For Miura, some of the visual art that he saw offers an analogy for his admittedly brief exposure to social and cultural Havana. “You have a kind of 1920s communist futuristic design, on top of ’60s–’70s pop art, on top of Takashi Murakami,” the contemporary artist known for bringing Japanese “low culture” into high art.

“Everything is happening at the same time because the country has just opened up,” says the composer. New layers of cultural influence are accreting over the old ones fast, as if making up for lost time.

“It’s almost like an onion: You peel one layer and then there is something surprising that comes up. It’s not just a time capsule, but it’s like weird twists of time and space.”

Barack Obama’s outreach to the island after decades of political stalemate is still reverberating in the streets of Havana. “People are definitely excited about this,” says Miura (who was repeatedly asked by residents whether he voted for Donald Trump. But, living in the U.S. on a green card, this Japanese citizen can’t vote here.)

“It was clear that Obama was so loved by Cubans for opening up the relationship.”

He adds, “One thing that’s for sure, when I spoke with some Cubans there, is that they don’t know what kind of change is coming” post-Fidel. While the current leader, Raul Castro, is more open to a market economy, what that will look like going forward — “nobody seems to really know.”

“I’m really curious to see how Cuba is going to go culturally and politically,” Miura says. Hopefully accompanied by Bates students, he adds, “I would love to go back to witness that change.”