Religious studies professor Marcus Bruce ’77 began a recent interview about Benjamin Mays by noting a historic coincidence.

“Since we’re talking about Mays, I’d forgotten how significant this day is,” Bruce said.

The day was Dec. 5, the 61st anniversary of a seminal moment in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement: the start of the year-long Montgomery bus boycott, sparked by Rosa Parks’ arrest and famously led by the young Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

And at a pivotal moment in the boycott, Bruce says, “Mays was instrumental” in bolstering King’s confidence to continue his leadership.

Bruce should know: He’s the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies, and last fall he taught a course on Mays, the 20th-century civil rights leader, theologian, Morehouse College president, mentor to King, and 1920 Bates graduate.

How did Mays influence King during the boycott?

How did Mays influence King during the boycott?

Sixty-one years ago, in the summer of 1956, King had left Montgomery midway through the boycott, first to appear at Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., and then to visit his parents in Atlanta, where he learned that he would be arrested if he returned to Montgomery.

King’s father invited prominent African American leaders, including Mays, to the King home in Atlanta to help his son think through the consequences of staying in Atlanta rather than going back and being arrested.

Many in the group urged King to stay in Atlanta, but King said he would return to Montgomery. Silence followed, and his father burst into tears. At that moment, King later wrote, “I looked at Dr. Mays, one of the great influences in my life. Perhaps he had heard my unspoken plea. At any rate, he was soon defending my position strongly. Then others joined in supporting me.”

At a point critical to not just the boycott but to the movement itself, it was Mays’ voice and support that King felt.

Did you ever meet Mays?

I met Dr. Mays once when I was a student. I was a member of what was called the Afro-American Society at Bates. We were having a potluck meal in the bottom of Parker Hall, and he surprised us. He just appeared out of nowhere. I don’t know why he was on campus but he just spent time with us and it was really wonderful.

For a long time, many of us at Bates didn’t know much about him other than he was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s mentor. In the 1990s, a few of us — the late Bob Branham, Beckie Conrad ’82, and myself — traveled to the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University to look at Mays’ papers for the 1994 Symposium at Bates celebrating the centennial of his birth. I began to get a strong sense of Mays’ influence on American religious history and thought during that trip and the conference that followed.

When I look at Mays and think about his relevance or importance, I think it goes back to his phrase that “Bates didn’t emancipate me, but it did me the greater service of helping me to emancipate myself.” That’s what stands out.

For Mays, emancipating himself meant competing with and doing better than white students in his studies and activities. What do you take away from his focus on competition to prove his self-worth?

He wanted to lay to rest any doubts that he, or anyone else for that matter, might have about his intellectual ability. Mays was born and raised in a segregated society where the prevailing idea was that African Americans were intellectually inferior.

He wanted to prove to himself that he could hold his own in any educational context. He thought Bates was a place where he could do that — where he would be accepted but also where he could challenge himself and learn to overcome any anxieties or obstacles that might arise. And he did very well.

Do we know if that was a typical experience of Southern African Americans who went to Northern schools, to frame their goals in competitive terms?

Certainly, it was true of W.E.B. Du Bois, who was born in Great Barrington, Mass., yet earned a degree from Fisk University and then got a second B.A. at Harvard because he wanted to prove himself there — he wanted to see if he could hold his own.

There were a number of African Americans who did this, but quite often the schools they wanted to attend wouldn’t admit them. Individuals like Mays and Du Bois were determined to demonstrate their ability to succeed in any academic environment, again laying to rest for themselves and others the negative stereotypes and myths about the capabilities of African Americans.

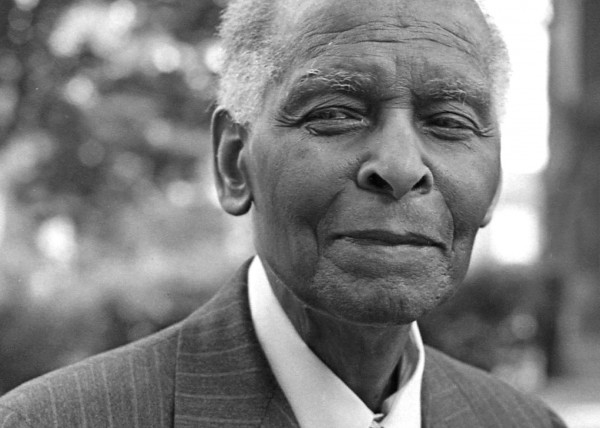

Benjamin Mays, Class of 1920, photographed in 1980 when he returned to Bates for his 60th Reunion. Photograph by Jim Daniels.

Mays begins his autobiography, Born to Rebel, at age 4 or 5 by describing his father being harassed by night riders. Instilled at an early age, that fear — of segregation, of the consequences of crossing the color line — was something that Mays fought against until his dying day.

For him, the color line wasn’t simply the cultural, social, or political practices of segregation. They were things that he didn’t want to internalize. He wanted to overcome them.

Since the presidential election, where are your students in their thinking?

They’re thinking about ways to remain engaged in the political process, ways to be heard. I keep holding up Mays as an example. I’ve said that Mays wasn’t able to vote until he was almost 52 years old. And from the moment he set out to get an education, Mays believed education would help liberate him from the fears and the normative ideas or practices around race and segregation.

Mays saw and experienced segregation in one form or another for his entire life. He was still preaching against different kinds of segregation until his dying day. So there’s this whole idea that you don’t give up the fight, that you never give up, that we’re always engaged in this struggle for emancipation.

So education still has the power to liberate students from fear?

That’s why Mays’ words are in our mission statement. We believe that education is emancipating. Mays looked at education as a way to liberate people from ignorance and fear and to help them to envision new possibilities for themselves and for society.

He said that he believed that everyone had something to give to humanity. And if they didn’t do the work that they were capable of, then that work wouldn’t get done.

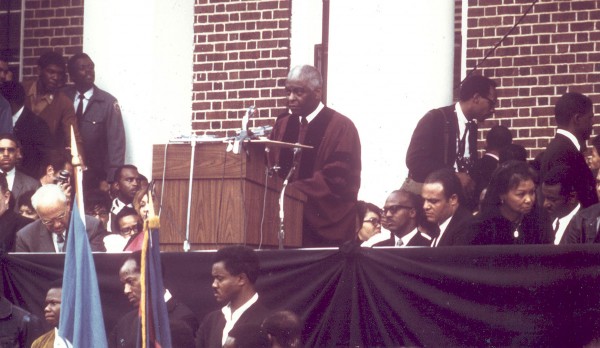

That connects to Mays’ eulogy for King, when he said that there’s no such thing as someone, like King, being “ahead of their time” because the time is “always ripe to do that which is right and that which needs to be done.”

We’re reading the eulogy now. I always think that’s so powerful, that he was able to say that, to have this vision of King as being “of his time” and speaking to his time in a very specific way. King seemed to view his life in the same way. He really does talk about being in this place at this moment.

Mays delivers the final eulogy for the slain Martin Luther King Jr. on April 9, 1968, at Morehouse College. Photograph courtesy of Howard University.

King also gives you a sense of his journey. At the time of the boycott, he talks about how his journey connected with the local leadership and action, with the discontent among people experiencing the injustices of segregation. And how there was power in one small, seemingly insignificant gesture by Rosa Parks of just sitting down — it wasn’t the first time — and how her being arrested connected with people and ignited something. All of this played a part in the emergence and organization of the Civil Rights movement.

To stay engaged in the process — that’s the challenge!

I think something like that is happening right now. People are being challenged to think: What does it mean to be an American citizen? What does it mean to be free? What involvement and what place do I have in the political process?

Your candidate may not have won but does that mean that you walk away from the process and leave the responsibility to someone else? Or is there work you can continue to do to promote your idea of what it means to be free or an American? To stay engaged in the process — that’s the challenge!

Free Will Baptists founded Bates. Is there something about how they interpreted their gospel and teachings that resembles what Mays and King were doing?

The Free Will Baptists’ social and political commitments — abolitionism, temperance, education — came from their religious convictions. They believed that it was their responsibility, their duty, to transform the world around them and to look at the Sermon on the Mount as their practical way: that you feed the hungry, you clothe the naked, you visit those who are in prison, and you take care of the homeless.

Mays, like King, believed and practiced a “social gospel” that applied to every aspect of individual’s life and involvement with others. If the gospel only meant something on Sunday mornings or in your private meditations, then that wasn’t really the gospel message. For Mays and Dr. King, the gospel had a social message, one of social reform, social change, and realizing the Kingdom of God in the world.

What should we know about Mays’ meeting with Mahatma Gandhi?

It shows that he was part of a small group of African American scholars and intellectuals who were looking at India’s struggle against imperialism and colonialism as a way to help their own strategies for addressing segregation in the U.S.

Mays engaged Gandhi around the whole question of nonviolent resistance. And when you see that happening in 1936, you see that he is thinking, “How can I use this same strategy, this same approach, in the U.S.?”

It also shows how he was becoming an international figure, too.

Was Mays ever criticized?

Sometimes people wonder just how involved he was in the civil rights movement. Well, he was very involved, educating the next generation of leaders, working behind the scenes, donating money, supporting the leadership and individuals within the movement, especially Dr. King and some others.

The only criticism that I do know of came later in the 1960s with a whole new generation of political activists. These were enormously important years in the consciousness of African Americans: black pride, Black Power, and a new kind of militant activism were emerging.

“Initially, my students just see Mays as someone ‘out there,'” says Marcus Bruce ’77, the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies. By the end of the course, they’ve begun to appreciate “the trials, tribulations, abuses he had to suffer.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Mays very firmly believed in the possibility of African Americans, but he wanted to go the route of education and help African Americans gain leadership positions in every field. Mays was seen by some younger activists as “old school” and out of step in this regard — as, on occasion, was King.

Recently I visited Paris and saw an exhibit called The Color Line at the Quai Branly Museum that looks at African American experience, from slavery to the Black Lives Matter movement, through the lens of art. When I came to the section on the 1960s, there were pictures of the Black Panthers, Angela Davis, and, in one glass case, Mays’ book Born to Rebel.

It struck me: Do they know the extent, intensity, and complexity of the differences and visions that existed between Mays’ and a new generation of African American activists? What we now celebrate as a period of rich diversity of ideas among African Americans was a painful and difficult period in Civil Rights history.

I have seen an interview with Mays where he talks about seeing the pro-KKK film Birth of a Nation in Lewiston, and afterward running back to campus because he feared for his safety.

He said it was the only time when he felt in danger in Lewiston. He felt real hostility and anger in that audience, and it frightened him. He saw the power of the medium to frighten people and generate mindless aggression and anger toward someone like him.

While he didn’t write specifically about Birth of a Nation, he wrote about another film, The Green Pastures, a popular Broadway musical in 1930 with an all-black cast that became a film with an all-black cast in 1936.

The movie depicts Bible stories through stereotypes of African Americans. It portrays God as a black man, “De Lawd,” speaking a black dialect — not correct or proper English speech — and scenarios that painted a quaint, folksy, stereotypically exaggerated image of African Americans and religious belief. Heaven is described as a fish fry.

Mays begins the book that is his dissertation, The Negro’s God: As Reflected in His Literature, by talking about The Green Pastures because he was bothered by the stereotypical depiction of how African Americans viewed God. He wanted his book to be a work of scholarship that recovered the richness and diversity of conceptions of African American ideas about God in their literature, in their scholarship, in their poetry.

Are there parts of Mays’ experience that don’t resonate with your students?

Many of my students raise questions about Mays’ particular attention to the role of race and gender in the education of young black men, especially the idea of Mays, when he was president of Morehouse, emphasizing the masculinity of young Morehouse men and their graduates.

I tell them that Mays taught the young African American men of Morehouse the “lessons” he had learned in his life and career, lessons in “how to be free in a segregated world,” how to define themselves by their “own terms in a world that offered no terms for their existence.”

Anna Marr ’17, an environmental studies major from Larchmont, N.Y., makes a point on Dec. 8 during the Benjamin Mays course taught by Marcus Bruce ’77, the Benjamin E. Mays Professor of Religious Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Initially, my students just see Mays as a prominent and successful African American who attended Bates. They’ve heard references to him at Bates but they don’t know him. By the end of the course, they’ve become more intimate with him and begun to appreciate the decisions and choices and the life he led, and the trials, tribulations, and abuses he had to suffer.

And they begin to understand why he designed the Morehouse educational experience in a particular way, always exhorting students to do their best, to be competitive, and to believe they were just as talented and deserving as everyone else in the world.

At weekly chapel gatherings, Mays would give Morehouse students a phrase or saying that they could hang on to — quotes that they would keep for the remainder of their lives, that would serve as principles that would guide them in any situation.

I tell my students about this practice and then ask them, “What guides you, what are your principles?” And I always emphasize that Mays is a fellow Bates College graduate. I say, “You can do as much, if not more, as Mays, a Bates graduate. What are you learning from your education? What are you taking away from your experience at Bates that will allow you to navigate the world and guide you through the rest of the world?”

What is another aspect of Mays that they might struggle with?

Sometimes Mays’ competitiveness, as you’ve described it, and his emphasis on always listing what he had achieved, is a bit off-putting to them. I had to learn to appreciate it myself. I thought, “Why does he keep listing this, that, and the other thing?” But I learned that it was a way for him to chart his course, assess his progress and to push himself to do even more.

Ben Coulibay ’17, a philosophy major from Philadelphia, joins the discussion on Dec. 8 during the Benjamin Mays course taught by Marcus Bruce ’77, the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The point is, he was always trying to see how far he had come and what he achieved. It wasn’t simply his ego. It was about, “How free am I? What have I done to improve the community, the nation and the world of which I am a part?” He did that by listing his accomplishments or what he had been able to achieve at Howard and Morehouse and throughout the course of his life and career.

So long before anybody appreciated him, Benjamin Mays appreciated himself.

This is a man who was the son of former slaves, and he wanted to remind people of the fact that he got a degree from Bates College, that he had earned a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, and that he was dean of the School of Religion at Howard University and president of Morehouse College for 27 years. He had come a long way and achieved a great deal!

So long before anybody appreciated him, Benjamin Mays appreciated himself. That is kind of amazing.

What’s the one thing we should know about Benjamin Mays?

He was a greater man and a greater individual than we know. He had a far greater and wider impact than we actually know.

Besides appreciating him as a writer — he wrote a weekly column for The Pittsburgh Courier, an influential African American newspaper, for years — and as a scholar, as someone involved in the Civil Rights movement, and as a mentor for King, he was also an international figure, too. This is a man who was part of YMCA International and the World Council of Churches. He met and worked with hundreds of leaders around the world and had leadership positions with various national and international organizations.

The other thing that strikes me is his ongoing struggle for emancipation. I started out with the phrase — “Bates didn’t emancipate me” — and then you look at what he meant by “emancipation,” and it’s ongoing.

When we think of “emancipation,” is it usually some 19th-century idea and event, the Emancipation Proclamation and a group of African Americans, some formerly enslaved, some free, who are struggling to define freedom for themselves and the country? No! The greatness of this country is that we keep defining “emancipation.”

The phrase that rings with me is Lincoln’s from the Gettysburg’s Address: “This nation shall have a new birth of freedom.” We tend to think that freedom was born a long time ago and it’s done. No! The process of defining freedom goes on.

Each Bates student — all of us here — is a new birth of freedom. Now are we going to articulate that? How are we going to do that? It’s not easy. It’s painful because somebody over there might think, “That’s a ridiculous idea.”

But that is part of the process. So that is what strikes me this year, that Mays represents a new birth of freedom and encourages all of us to work through our ideas and our practice of freedom.

Corrections to this story were published at 6 p.m. Jan. 6, 2017.