Q&A: Margaret Creighton on power and resistance in the Rainbow City

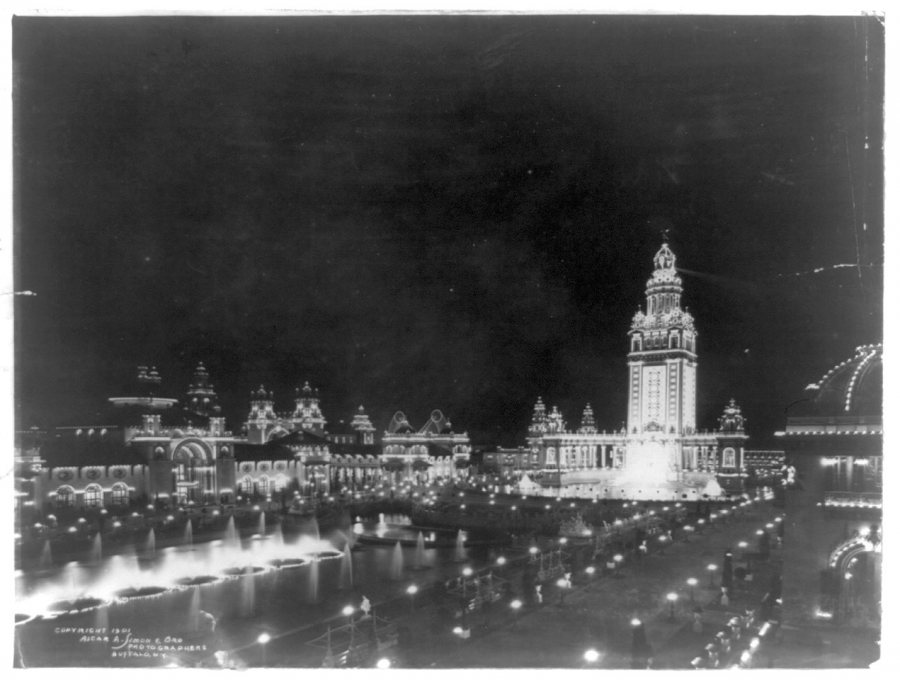

The Pan-American Exposition at night, illuminated by thousands and thousands of incandescent bulbs. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

In the late 1890s, against a backdrop of surging American wealth, industrial might, and self-confidence, the city leaders of Buffalo, N.Y., decided to make a play for national prominence by holding a world’s fair.

Buffalo’s Pan-American Exposition opened in May 1901, showcasing accomplishments of the Western Hemisphere with the U.S. as the putative standard bearer. Called the “Rainbow City” because of its colorful exhibition halls, the exposition also celebrated the still-novel capabilities of electricity, generated at Niagara Falls and powering stunning illumination displays.

Professor of History Margaret Creighton is the author of The Electrifying Fall of Rainbow City. (Will Ash)

The fair was the latest in a series of international expositions, beginning 50 years prior with London’s Great Exhibition, that used achievements in culture, trade, and especially technology to express national pride. More than pride, though, the Buffalo fair ended up exemplifying American hubris.

While a popular success, the fair was a financial failure. It was also an exercise in racism and other expressions of cultural arrogance that are repulsive by today’s standards. And the fair earned lasting infamy as the place where, in September 1901, a mentally ill anarchist named Leon Czolgosz assassinated U.S. President William McKinley.

A native Buffalonian, Professor of History Margaret Creighton tells the story of the fair in her latest book, The Electrifying Fall of Rainbow City: Spectacle and Assassination at the 1901 World’s Fair, published in October by W.W. Norton.

The book’s plot and characters could make a Robert Altman film — a cruel animal trainer, a woman who goes over the falls in a barrel, a little person who escapes her starring role in the fair to be with her lover. But in a conversation in December, Creighton made it clear that her real interest in the Pan-American Exposition is what it tells us about power and people who push back against it.

What were the claims to fame that Buffalo hoped to showcase?

Buffalo was the eighth-biggest U.S. city at the turn of the 20th century. It was the site of numerous railways, and boasted that 40 million people could reach the city in a day’s journey or less. It had state-of-the-art architecture, state-of-the-art asphalt streets, and magnificent electric lights powered by Niagara Falls.

Buffalo hoped that it would challenge Cleveland as an economic hub, and certainly hoped to establish itself as the second-biggest city in New York state. It also hoped to upstage Chicago — Chicago’s fair of 1893, the so-called White City, had been a hugely popular and masterful event.

President McKinley visited toward the end of the fair. What were the organizers’ hopes for the visit, and how did it play out?

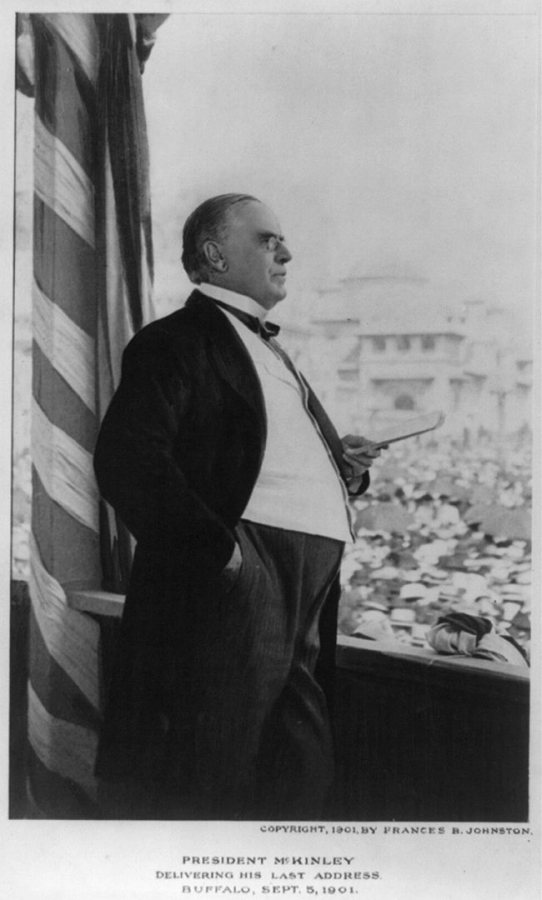

President William McKinley addresses the Pan-American Exposition on Sept. 5, 1901, the day before his assassination. (Frances B. Johnston/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

During the summer, Pan-American fair directors realized they weren’t attracting as many people as they would have liked. Chicago’s White City numbers seemed out of reach. But the Buffalonians knew that in September, things would turn around because McKinley and his ailing wife, Ida, were coming to town. They were sure this would reverse the revenue trend.

McKinley arrived on Sept. 4 and gave a huge speech on the Esplanade the next day, including the often-quoted words that world’s fairs were the “timekeepers of progress.” People flooded into Buffalo to see him.

Then, on his second day at the fair, he held a reception in the Temple of Music. Among the people in the receiving line was a young, white, clean-cut man who had his hand wrapped up in a handkerchief. The security guards, though, were focused on a tall African American man standing behind him. And so this guy slipped through the radar, pulled out a revolver and shot McKinley.

In a weird way, the organizers looked for a silver lining in the shooting.

This was a huge blow to Buffalo. They’d been pinning all their hopes on McKinley. So the city found itself deeply humiliated, and worried that this fair was now going to be an utter failure.

But then two to three days out, McKinley seemed to be recovering. Buffalo, in fact, had now accomplished a miracle: Its superb medical professionals had accomplished what few others had in cases like this, saving someone who had been shot in the abdomen.

So, in a flash, Buffalo recovered its pride and began to celebrate its achievement. City leaders imagined Buffalo would become the site of the temporary White House, and a site of national importance — so what they hadn’t been able to achieve through the fair, they now got to accomplish through the miracles of medicine.

And then eight days after the shooting, all of a sudden, McKinley began to fail. And within a matter of hours, he was dead. Now Buffalo not only had to suffer the death of McKinley in their magical land, but also the ignominy that was attached to their early boasting and overconfidence.

For the entire country, in fact, it was a moment of intense roller-coaster emotions.

How is Electrifying Fall a timely story?

The fair’s Temple of Music was the site of McKinley’s assassination. (C.D. Arnold/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

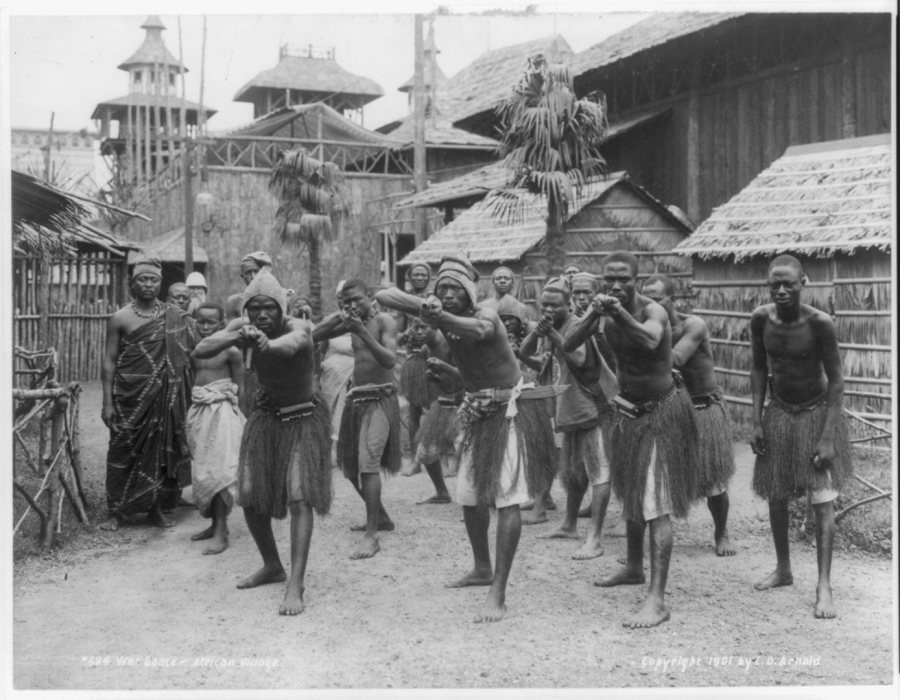

It’s all about arrogance, all about unjust power, all about the belief in American exceptionalism. Those are themes that are resonant today, obviously. The book also tells how the fair’s displays of white supremacy echoed the celebration of the subjugation of Niagara Falls and other “natural” elements.

But the book is also a narrative about those who resisted and attempted to subvert that power and that arrogance. For example, Native Americans and African Americans challenged demeaning representations on the fairgrounds in creative ways.

Speaking of power and arrogance, talk about Frank Bostock, who provided the fair’s animal show.

The self-proclaimed Animal King really saw himself as a match to the exhibits about cultural and economic power. He was all about commanding and controlling the animal world. He bragged about how, unlike African and Asian natives, he could go in and domesticate any animal he wanted. One of his signature acts was a lion trainer who sat in a rocking chair surrounded by 14 or 15 lions.

“War Dance — African Village.” The representation of Africans and African Americans at the world’s fair drew protests. (C.D. Arnold/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Bostock brought into Buffalo an elephant that he tamed, Jumbo II. At the end of the fair, he decided he was going to try to make money by electrocuting Jumbo II. By this time, of course, McKinley’s assassin, Leon Czolgosz, had been electrocuted. So electricity gets a double billing here: this miraculous wonder, and at the same time this killer technology. [Spoiler alert: Jumbo II lives.]

Bostock also dominated, or tried to dominate, a woman who is one of your key figures — Alice Cenda, aka Chiquita.

I wanted to talk about women in the book, and one of the individuals I focus on is a young Latina who was a little person from Mexico — although they billed her as Cuban. They made her the mascot of the fair, which is just telling in all sorts of different ways. At two feet tall, she resisted being treated as a child. She fell in love and escaped from her manager, and he kidnapped her again.

Why did you choose to write about the Rainbow City?

My book The Colors of Courage is about the Battle of Gettysburg and some of its forgotten stories, especially the roles African Americans and white women played in the battle. That was both a very local and a very national story, with a clear beginning and end.

My book The Colors of Courage is about the Battle of Gettysburg and some of its forgotten stories, especially the roles African Americans and white women played in the battle. That was both a very local and a very national story, with a clear beginning and end.

I’m increasingly drawn to writing narrative history, despite what I teach my Bates students about an explicit thesis and argument. So I was on the hunt for a similar event, something that might interest readers generally but was grounded in a specific locality.

I had assigned Eric Larsen’s wonderful book about Chicago and the World’s Fair, Devil in the White City, to some of my students and they loved it. So we talked about world’s fairs, and it occurred to me that I had actually grown up near the site of a world’s fair — which I had ignored for most of my life. But I thought I would go back to Buffalo and see what remained. It turned out the fairgrounds have pretty much disappeared, but written evidence remained in abundance.

How did producing this book affect your feelings about your hometown, which 30 or 40 years ago was suffering tough times like a lot of other industrial towns?

When I was growing up in Buffalo, the city was circling downward. Going back, though, was an eye-opener. Things are booming in western New York, and there’s a tremendous sense of optimism. And so I was pleased to be able to deliver a history that, while not necessarily a happy story, could contribute to a greater understanding of times past.