From Sunday evening’s interfaith service to Tuesday’s MLK Day Read-In at a local elementary school, immerse yourself in the images, ideas, and rhetoric of the Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration at Bates.

7:14 p.m. Jan. 15 — Peter J. Gomes Chapel

On Sunday evening, the Gospelaires a cappella group performs at the start of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Interfaith Service in the Gomes Chapel.

They sang “This Is My Song,” which includes these lines:

This is my home, the country where my heart is

Here are my hopes, my dreams, my sacred shrine.

But other hearts in other lands are beating,

With hopes and dreams as true and high as mine.

7:45 p.m. Jan. 15 — Peter J. Gomes Chapel

The Rev. Dr. Charles Howard, university chaplain at the University of Pennsylvania, delivers the sermon. He told a story about meeting the late Peter Gomes ’65, for whom the Bates chapel was named in 2012.

At the time, Howard had recently been appointed university chaplain at Penn, and he asked Gomes, the legendary Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial Church, for advice “for a rookie chaplain.”

Gomes said, “Always walk into the room as if you are the most important person there.”

Which got a laugh. But Gomes continued, “Always walk into the room as if you are the most important person there…because to God you are.”

In other words, as Howard told the gathering in Gomes Chapel, “there is something bigger on our side that won’t let us lose” in the work for social justice and fairness.

“Walk into 2017 as if you are the most important person in the room…because to God you are.”

9:34 a.m. Jan. 16 — Peter J. Gomes Chapel

Monday morning, a standing-room only crowd gathers in the Chapel to hear historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad deliver the MLK Day keynote.

In her welcome, President Clayton Spencer noted that “injustice and violence have been with us in this country since our founding. Our history cannot be told, though it often is, without the narratives of the slave trade, of slavery, of Jim Crow, and of the battles for civil rights, economic justice, and freedom from state violence.”

Martin Luther King Jr. Day, she said, “takes on this history in our chosen theme, ‘Reparations: Addressing Racial Injustices.'”

Because reparations “begin with acknowledgement,” she said, this year’s theme “challenges us to ask ourselves how we can move beyond the ‘fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity’ that Dr. King warned us of in 1967 — a fantasy that assumes American society is hospital to fair play and that steady progress toward racial harmony is inevitable.”

9:59 a.m. Jan. 16 — Peter J. Gomes Chapel

Muhammad delivers his address, “No Reparations Without Racial Education: Martin Luther King on the Tyranny of Ignorance.”

Muhammad reminded his Bates audience that understanding America’s history of racial injustice is the first step toward redressing that injustice.

“Since it is not OK to teach our children to deny the Jewish Holocaust, then why is it OK in far too many schools and homes to deny the centrality of slavery to the American story?” he wondered.

Later, Muhammad said:

Too often we treat history like it is an opinion. I’ve served on national and local committees to solve this problem or that, and I’ve watched educated people invoke their own experiences as historical proof.

We all have opinions, but we are not all historically literate, never mind fluent. The same problem of climate change denial holds in how most Americans think about our past — we at least give economists and environmentalists a chance to shake our beliefs. Historians, not so much.

10:31 a.m. Jan. 16 — Peter J. Gomes Chapel

After his talk, Muhammad greets Lewiston High School students who are members of the 21st Century Leadership Program.

Another stunning point made by Muhammad was that, in a sense, the Obama presidency closed the book on civil-rights era notions of progress.

With Obama, Americans were told how “racial representation and the content of one’s character are the perfect antidotes to racism.”

“But we were mistaken,” said Muhammad, who added:

The half-century-old rules and standard operating procedures for racial advancement are now obsolete. There is no racial barrier left to be broken. There is no office in the land blacks first can ascend — from mayors to governors to attorney generals, and now the presidency — that will serve as a magical platform for saving black or brown people and the soul of a nation from its racist past.

America’s institutions cannot be made over by simply dressing them up in more shades of brown and expecting a more just and equitable outcome. In this new era, the structures and the values of our institutions are the challenges we must now unflinchingly confront.

11:07 a.m. Jan. 16, Pettengill Classroom G52

Different day, same old ripoff.

The music industry’s longstanding agility in stealing from black artists was the topic of “A Cultural Debt,” led by Associate Professor of Music Dale Chapman, seen here speaking in front of a projected image of Count Basie and Benny Goodman.

It’s a sorry story that begins as far back as the 1840s and the minstrel shows in which white performers in blackface parodied African American performance. Citing Eric Lott’s 1993 study Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, Chapman pointed out that the minstrel shows constituted a kind of “politics of ridicule” that helped white working-class Americans keep black culture in its place.

White jazz musicians like Paul Whiteman aimed to “make a lady” out of black jazz for white audiences. Sun Records owner Sam Phillips, through white artists like Elvis Presley, took the other route and cashed in by bottling the vitality of black music for mainstream consumption.

Labels like Atlantic cheated African American hitmakers out of revenues from the sales and publishing of their music — but when rappers found success decades later by sampling older recordings, the industry turned the tables, so to speak, and hauled them into court for theft of intellectual property.

As the people in the classroom sang jazz riffs, tapped toes to Benny Goodman, and swayed heads to Ruth Brown, it was a living demonstration that the thieves at least had good taste.

As Chapman said, even as the white establishment seeks to co-opt black culture for profit or power, there is a fascination “and very real desire for the cultural and musical practices of African Americans that would renew itself again and again and again.”

Or, as Smokey Robinson said, sometimes the hunter gets captured by the game. — Doug Hubley

10:52 a.m. Jan. 16 — Hedge Hall Classroom 106

In a full Hedge Hall classroom, Associate Professor of History Joe Hall (right) introduces, from left, Esther Attean, Kathy Paul, and Penthea Burns, women at the forefront of efforts in Maine to confront, expose, and help to heal the harm done to Native American children by the state’s child welfare system.

“It has gone on for generations,” Hall said in his introduction to the session, co-organized by Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill. “But for all the importance of history, it is also incredibly important to recognize that these are not issues that have been forgotten. They are issues of the present.”

History was on the mind of Attean, a member of Maine’s Passamaquoddy Tribe, as she told the gathering how, as she grew up, “it was really easy to buy into the racist narrative that there’s something wrong with us.”

Since the 1800s, one thread of the narrative tried to persuade Maine’s Native Americans that they were poor parents. Why else would the children of Maine’s four Wabanaki tribes — the Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Micmac, and Maliseet — be taken into foster care at rates far higher than non-Native children?

But as a state-sponsored Truth and Reconciliation Commission found in 2015, the systemic practice reflected dire problems not with Native American families but with the state’s child welfare system, abuses that amounted to “cultural genocide.”

Attean and Burns spoke from their perspectives as co-directors of Maine-Wabanaki REACH, a program that grew out of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s work and now devotes itself to reconciliation, engagement, advocacy, change, and healing for Maine’s Wabanaki citizens, who number 8,000 today. Joining Attean and Burns was Kathy Paul, a Penobscot elder.

“We realized there was not a possibility of going forward until there was a common understanding of what had happened,” she said.

Back in 1978, the federal Indian Child Welfare Act was supposed to end the disproportionate rates at which states were removing Native American children from their traditional homes.

But years later in Maine, well-intentioned new policies and improved training still hadn’t gotten to the root of the problem: a racist culture within the state child-welfare establishment was “alive and well,” said Burns, but “never talked about” publicly.

“We realized there was not a possibility of going forward until there was a common understanding of what had happened,” she said.

In large part due to Attean and Burns’ advocacy, Maine established the landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the first of its kind in the U.S. to address Native child welfare.

Thanks to the commission’s work and other efforts, racist narratives against the Wabanaki are slowly being dismantled. “It’s liberating to know that there’s nothing wrong with us,” Attean said.

“Native American children are resilient” in the face of years of abuses by the state, said Attean. “But I don’t want them to have to be resilient. I want them to have a world where they can just be kids.” — H. Jay Burns

Screened during the session, this film documents the work of the Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

11:29 a.m. Jan. 16 — Ladd Library

In Ladd Library, children read books from the college’s Picture Book Project.

Founded by children’s book creator Anne Sibley O’Brien and Associate Professor of Psychology Krista Aronson, the Picture Book Project comprises books, published since 2002, featuring racially diverse characters.

Numbering 1,500 titles, “it is the only circulating library collection of its kind,” said Aronson.

At the start of the session, O’Brien read from Last Stop on Market Street, a 2016 Newbery Medal–winning book by Matt de la Peña.

As she read, the children listened for how the main character, an African American grandmother, acted as a “hero,” teaching her grandson how to see beauty in people and in the world that others might easily dismiss.

Then, the children chose and read stories from the collection. Afterwards, they drew pictures of themselves as a “hero” taking action with the characters in their story.

“These books illustrate actions and experiences that can easily be happening now,” said O’Brien. “Regardless of whether you are 5, 7, or 11, everybody can follow Martin Luther King’s footsteps by asking questions and giving back to our communities. We can all be ‘action heroes’ for social justice.”

Representing people of color in children’s literature is “valuable for many reasons,” said Aronson, not the least of which for how it supports literacy. “When children of color to see themselves depicted in books, they retain and recall more plot and character information because they feel connected.” — Sarah Rothmann ’19

2:22 p.m. Jan. 16 — Pettengill Hall Classroom G52

“This raised my awareness of what Division I athletes go through,” said Adedire Fakorede ’18 of Newark, N.J., shown speaking during the panel discussion on “Rethinking Reparations: Bending the Arc of Athletics Toward Justice.”

Joining Fakorede were, from left, Peter Lasagna, head coach of men’s lacrosse; Erica Rand, Whitehouse Professor of Art and Visual Culture; Gwen Lexow, Title IX officer; and Ameer Loggins, who is pursuing his doctorate in African diaspora studies at Berkeley.

The panel looked at how NCAA Division I athletes — especially football and basketball players, who are mostly African American — generate billions in revenue for their institutions, yet see little of it.

Panelists use the words “plantation” and “sharecropper” to describe the oppressive place of athletes in the Division I money machine.

“It’s a deeply regressive redistributive paradigm,” said moderator Chris Petrella ’06, a lecturer in American cultural studies at Bates. “Those who are creating the product — the laborers, the athletes — rarely see the fruits of their hard work.”

For many Division I athletes, academics often take a back seat, a fact not lost on Fakorede, an All-American thrower for Bates track and field and president of Bates Student Government.

At Bates, “I can focus on my course load and still perform at a high level athletically,” he said.

“My dad always instilled in me the importance of the brain. He’d say that your body gets old and wears out but you can always pick up a book,” Fakorede said.

In life, he added, “there’s much more potential in exercising my brain with the same rigor” that one might apply to sports. — Aaron Morse

2:44 p.m. Jan. 16 — Pettengill Hall Classroom G21

Organizers Allen Kendunga ’18 (standing) of Kigali, Rwanda, and Andrew Segal ’17 (left) of Glencoe, Ill., joined by Admission counselor Matt Williams (right), listen to a discussion during their session looking at Bates’ future through the lens of its past.

Earlier in the day, keynote speaker Khalil Mohammad had said it’s time we look at the history and character of our institutions, many of which were “built on the backs of the enslaved.”

During Kendunga and Segal’s session, the institutional character in question was Bates’.

While Bates was indeed founded by a radical abolitionist, Oren Cheney, it also benefited from slavery, said Segal, a religious studies major from Glencoe, Ill., because textile mill owner Benjamin Bates, for whom Bates is named, undoubtedly profited from Southern cotton.

After that history lesson, the organizers asked their audience a more forward-looking question about Bates’ character. If Bates in 1855 was a century ahead of its peers by being open to men and women and to all religions and races, what should Bates do today to stay ahead of its peers?

The audience offered ideas ranging from a required social-justice course and increased financial aid to stepped-up sustainability programs.

Having a progressive history doesn’t give Bates a lifetime pass, said Annakay Wright ’17, a women and gender studies major from Brooklyn, N.Y.

“Just because you have an alumnus like Benjamin Mays,” the great civil rights leader and 1920 Bates alumnus, “doesn’t make Bates like Benjamin Mays. Students have to participate” to effect institutional change.

In closing, Kendunga, a politics major from Kigali, Rwanda, thanked the group for creating a “comfortable space to discuss uncomfortable topics. That’s what it means to be progressive.” — H. Jay Burns

2:52 p.m. Jan. 16 — Commons Room 221

Gideon Ikpekaogu ‘17 of Lagos, Nigeria, engages in a key aspect of MLK Day: listening.

Ikpekaogu and fellow students of Professor of Latin American Studies Baltasar Fra-Molinero presented findings from their coursework about the division of race, socioeconomic status, drugs, land, and access to natural resources in Colombia.

“More than six million people, mainly from African descent, have been displaced in Colombia,” explained Madison Ekey ‘17 of Bozeman, Mont. “Multinational corporations are taking advantage of this crisis for resource extraction and profit.”

An audience member challenged that conclusion. “One cannot quantify who is to blame because the conflict is much more complicated.”

As the gathering broke into discussion groups, Ikpekaogu encouraged his group to strive for self-awareness.

“Whether it is known to ourselves or not, we all have an implicit self-bias,” said Ikpekaogu. “We need to break away from stereotypical ideas of black identity and focus on the need for equal civil rights and participation.” — Sarah Rothmann ’19

3:08 p.m. Jan. 16 — Pettengill Hall Classroom G10

In a session titled “Wada-yaal” — Somali for “co-existence” — musician Hadith Bani-Adam tells true stories through songs that promote peace and what he calls “deradicalization.”

Musician Hadith Bani-Adam performs during the MLK Day session:

Bani-Adam heard some of those stories while living in Kenya’s huge Dadaab refugee camp, whose threatened closure this year would send nearly 300,000 residents back to chaos in Somalia.

In a packed classroom, the soft-spoken Bani-Adam described his journey and philosophy — and he played his oud and sang, supported on percussion by Ness Smith-Davidoff and on viola by session host and faculty member Greg Boardman.

Bani-Adam’s songs professed affection for “Mama Africa” and lamented lovers separated when they left Dabaab. In “I Am Somali,” quick shifts among languages showed that Somali identity transcends national boundaries.

Living in the U.S. since 2016, Bani-Adam continues the peace activism that he brought from Somalia to Dabaab. A devout Muslim, he believes that people of faith who understand other religions are less susceptible to devils quoting scripture.

“Every community has black sheep [who] twist everything,” he said. “I’m going to untwist it with my music.” — Doug Hubley

3:30 p.m. Jan. 16 — Commons Room 226

Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill watches a video interview with author Ta-Nehisi Coates, seen on the monitor.

The session, co-organized by Hill, Associate Professor of Philosophy Susan Stark, and students, examined Coates’ 2014 article on reparations in The Atlantic.

3:52 p.m. Jan. 16 — Olin Arts Center Concert Hall

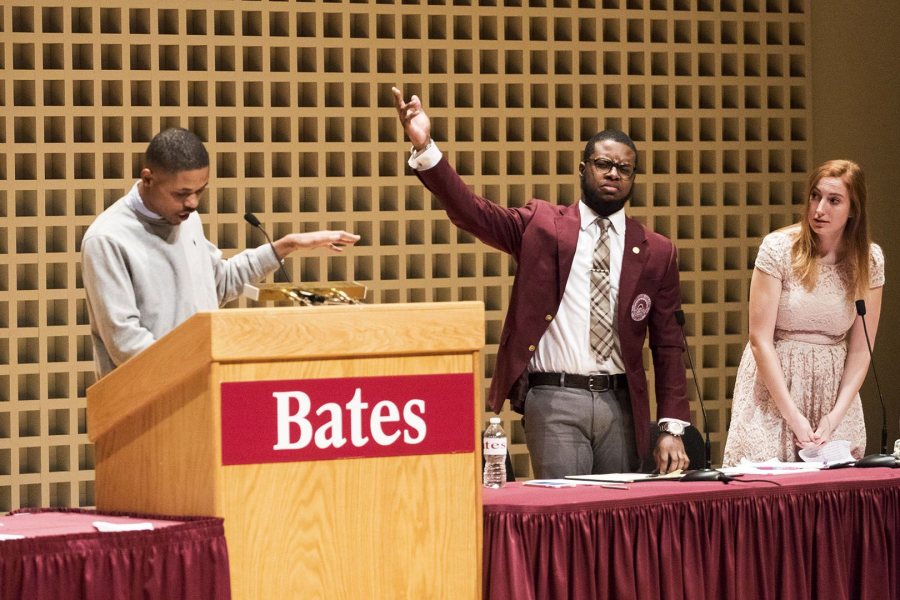

At the podium, Director of Debate Jan Hovden greets a packed Olin Arts Center Concert Hall for the annual Benjamin Elijah Mays Class of 1920 Debate, featuring debaters from Bates and Morehouse colleges.

This year, the debaters took on a topic that’s older than the New Deal.

That is, should we trust government programs to repair social ills? Or, in the context of reparations, should the government instead put money directly into the pockets of those who’ve been wronged?

That either/or was captured in the motion, “This House believes the state should exclusively focus on rectifying current inequalities to the exclusion of compensating for historical injustices.”

Tessa Holtzman ’17 of Bates, a politics major from Las Cruces, N.M., outlined the Government’s case to support “rectifying current inequalities” through targeted federal programs and government spending.

“The government should be driven by utilitarian needs,” she said. “The Government should not be based on morals and moral claims — which is what reparations are inherently — but on outcomes. We are able to get better outcomes because we are able to look at what communities specifically need and the inequalities they are facing.”

Not so fast, said Morehouse junior Mati Baker, an African American studies major from Baltimore. A utilitarian framework, he said, is “one that benefits the many with the least detriment to the few.” That’s the “same ideology that has enabled the majority to continue to promote policies that maintain white privilege.

“If we had had a government that was moral, we possibly would not have had the years of Jim Crow segregation that we are here talking about today.”

4:20 p.m. Jan. 16 — Olin Arts Center Concert Hall

Morehouse debater Sha’Heed Brooks, at the lectern, waves off a point-of-information request from Baker of Morehouse and Zoë Seaman-Grant ’17 of Bates.

Brooks, a sophomore philosophy major from Fayetteville, N.C., went on the offensive, attacking the Opposition’s case for reparations.

Reparations, he said, focuses “on past historical injustices to the exclusion of present inequalities.” And that would “only perpetuate a cycle of tragedy, oppression, and marginalization.”

Furthermore, he added, “their side never deals with mass incarceration. Their side never deals with police brutality in a way that we can only get when we focus on current inequalities that individuals face” through targeted federal programs.

Seaman-Grant took to the lectern to explain that reparations would, indeed, stop the cycle of oppression.

Reparations, she said, are “about how we give autonomy back to a community that has been denied it for centuries, through enslavement, through prisons, and through the denial of capital to black Americans, who were not given access to what was given to white veterans.”

The right approach, she continued, “is not by obscuring those past injustices but by acknowledging them, confronting them, and giving back the capital that was stolen. We think [African Americans] have a right to it because they have been so consistently denied freedom.

“And we need to do this now.”

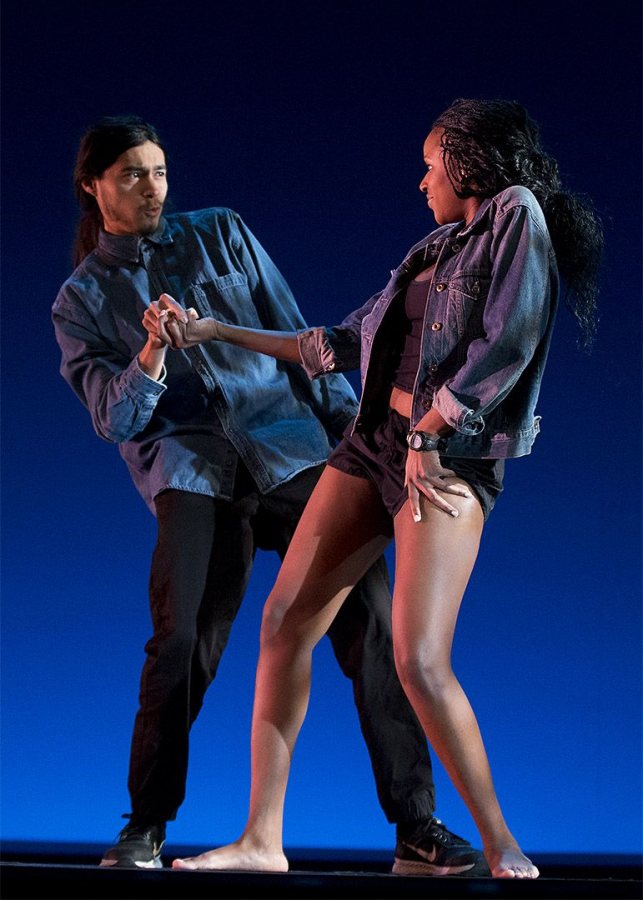

8:10 p.m. Jan. 16 — Olin Arts Center Concert Hall

Emilio Valadez ’18 of San Antonio, Texas, and Angie Kemfack ’19 of Missouri City, Texas, perform with Sankofa, a student group that performs an original production each year on the evening of MLK Day.

Sankofa explores the history and experiences of the African diaspora through performance, and this year’s show was titled Testimonies of Melanin Magic.

“The production was a means of voicing scenarios of common misconceptions of blackness and detailing how people representing the African diaspora cope with oppression,” said director Britiny Lee ’19 of Cleveland.

8:40 p.m. Jan. 16 — Olin Arts Center Concert Hall

Sankofa director Britiny Lee answers a question after the show. At left is assistant director Rakiya Mohamed ’18 of Auburn, Maine, one of last year’s co-directors.

It was an honor, Lee said, to develop the production and “let the rest of the Bates community in on issues we face that others may have been oblivious of.”

A lesson Lee wants to share is that “you can’t judge from the outside looking in, because everyone is unique and has something special to bring to the table. We must try to walk in one another’s shoes and try to understand before we shun.”

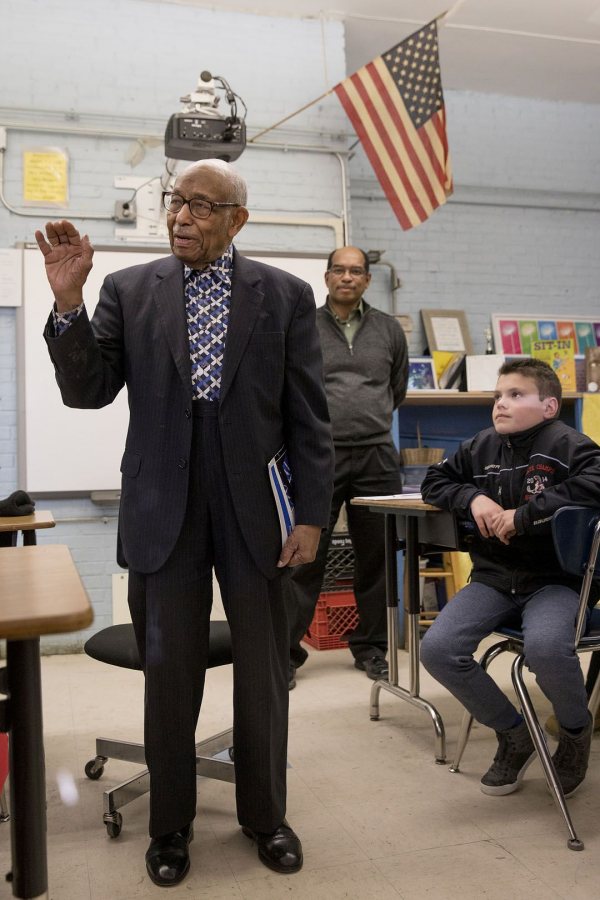

1:58 p.m. Jan. 17 — Martel Elementary School

As his son, Associate Dean of Students James F. Reese, listens proudly, the Rev. James F. Reese, age 93, tells sixth-graders at Martel Elementary School in Lewiston what it was like to meet Martin Luther King Jr. in 1960 and witness King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963.

While pastor of the First United Presbyterian Church at Knoxville College from 1959 to 1967, the elder Reese led sit-ins protesting Jim Crow laws and practices.

Reese’s visit was part of the school’s annual MLK Day Read-In.