When I ask about the weather, my smartphone chirps back an answer: “It doesn’t look so nice tomorrow.”

That’s doubly unsurprising. One, it’s February in Maine during a historic stretch of snowy weather. Two, a phone is supposed to answer questions.

But here’s a surprise. We tend to think that new ideas are the fuel for today’s technology. Yet voice recognition is one of the “many things that people have tried before that now work,” says Susan Dumais ’75, a Distinguished Scientist with Microsoft Research in Redmond, Wash.

A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering, Dumais visited campus in February as the College Key’s Distinguished Alumna in Residence, meeting with students and giving a talk on Feb. 1.

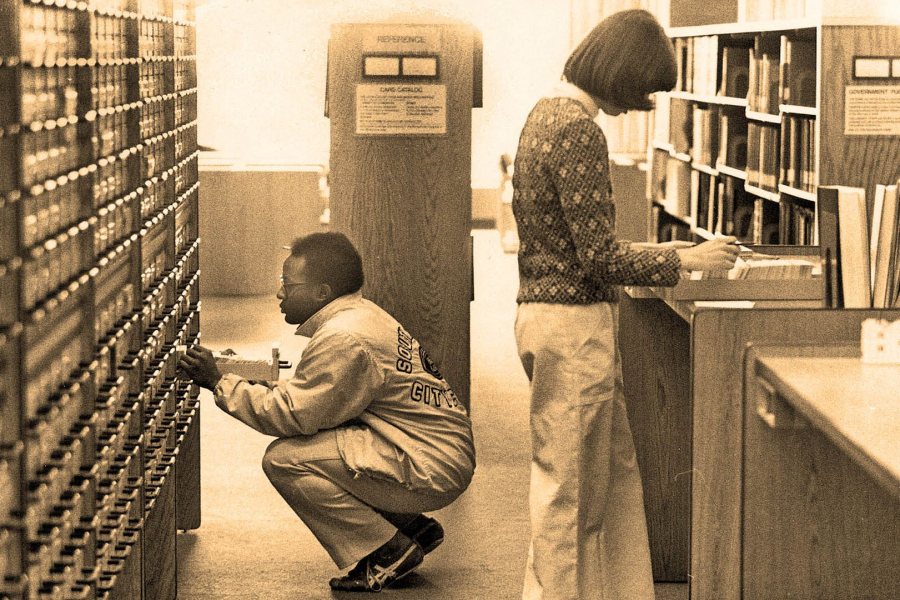

College Key Distinguished Alumna in Residence Susan Dumais ’75 gives a talk on Feb. 1 in the Olin Arts Center Concert Hall in front of an image showing a bygone way to retrieve information: the card catalog. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Back in the 1980s, when Dumais was at Bell Labs, one ongoing project was to get a computer to recognize correctly whether “yes” or “no” was answered to the question, “Will you accept this collect call?”

“Years and years and years of work went into that,” Dumais says. The project did succeed in the 1990s (though collect calls are going the way of the typewriter).

So, what makes today’s “new” technology possible? She points to better computational models, more computational horsepower, and access to much richer data.

In the case of voice recognition, it means access to vast amounts of spoken language with corresponding transcriptions, which makes it “easier to map various acoustic features to the resulting words,” she says.

“So when you search for ‘Who is the best teacher?’ the results include pages that use the word ‘professor’ even if they don’t use the word ‘teacher.'”

Another old idea whose time has come belongs to Dumais herself. In 1990 — way before Google or Bing — she and fellow researchers developed an information retrieval process known as “latent semantic indexing.” In recent years, LSI-related ideas have “been a big splash,” she says.

That’s because LSI enables search engines to retrieve the information that we’re actually looking for. “So when you search for ‘Who is the best teacher?’ the results include pages that use the word ‘professor’ even if they don’t use the word ‘teacher,’ ” Dumais explains.

Susan Dumais ’75 laughs with Professor Emeritus of Psychology John Kelsey before her talk on Feb. 1. Dumais first met Kelsey in the 1970s when she was a doctoral student at the University of Indiana, where he was starting his faculty career. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Simply put, LSI helps a search engine respond to queries by “discovering words that are semantically the same even though they aren’t literally the same,” she says.

The idea existed 25 years ago but “the time wasn’t right,” she says. Today, computers can swiftly learn these more nuanced word relationships thanks to the availability of much larger collections of text and more powerful computational resources.

Though advances in computing power are turning yesterday’s ideas into today’s tools, the demands of today’s tools are also keeping those ideas viable.

“How we use this technology — such as everyone carrying a smartphone — makes these ideas even more necessary now,” Dumais says.