“Different art forms can speak to each other in powerful ways, and that’s always important to remember,” says photographer and studio art major Calvin Reedy ’17 of Wilton, Conn.

Reedy was reminded of this truth last fall, when he was starting to feel stuck as he made a series of group portraits for the 2017 Senior Thesis Exhibition. Pamela Johnson, an associate professor of art and visual culture who advises the senior studio art majors during the fall semester, helped shake him loose.

17 Senior Artists in 2017

View artwork and artists’ statements from the Senior Thesis Exhibition, showing at the Bates Museum of Art through May 27.

Johnson, says Reedy, showed him “a clipping of a New York Times photograph of dancers — they were moving together as their bodies were pressed up against each other — and she encouraged me to look at dance to see how bodies interact and move together.

“While it makes perfect sense, I hadn’t thought of that before because I was so focused on looking mainly at photography for inspiration.”

Bates’ senior exhibition is always a lively conversation among genres. But this year’s edition, which runs through May 27, is especially rich, with 17 artists represented.

“The show includes drawings, paintings, prints, collages, sculptures, photographs, and vessel-based ceramics, as well as variants that are somewhere in between some of those mediums,” says Robert Feintuch, senior lecturer in AVC and adviser to the artists in the winter semester.

Cash Hadean ’18 of New Orleans inspects a sculpture by Jose Herrera during the April 7 opening of the Senior Thesis Exhibition. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Of course, the senior show always provokes lively, and valuable, conversation among artists too, making the studio wing of the Olin Arts Center a happening place — especially as the exhibition opening draws near and the scramble to finish work is on.

This year, “we interacted with each other frequently by leaving studio doors open and asking that others look at what we were working on,” says Mary Grace Schwalbe of Concord, N.C., whose paintings and drawings challenge notions of feminine beauty.

“It was great that there were various mediums among us, because it exposed us to different ways of working and made us consider the different thought processes behind art making.”

Feintuch, says Reedy, “is great at identifying themes in our work, and identifying what works well so that we can have a cohesive body of work for the show.”

For the exhibiting artists, preparing for the show is a lesson in seeing the forest as well as the trees. “Preparing a body of work that was coherent forced me to place restrictions on my art-making process so that the pieces felt connected,” says Schwalbe.

“Working on individual pieces for classes in the past, I didn’t have to think about how what I was working on would interact with the other pieces I had produced, but this was obviously a huge consideration during thesis.”

A print by Jackson Whitehouse ’17 is displayed during the Senior Thesis Exhibition in the Museum of Art. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Feintuch, says Reedy, “is great at identifying themes in our work, and identifying what works well so that we can have a cohesive body of work for the show.” Under Feintuch’s guidance, Reedy worked to ensure that a video piece complemented his still images — “not only with the same visual aesthetic, but also with the same quietness and softness that comes through in the photographs.”

Carolina González Valencia, Mellon Diversity and Faculty Renewal Postdoctoral Fellow in AVC, suggested that Reedy branch out into video and consulted with him along the way.

“My photography led me to video work, and maybe that will one day lead to performance, installation, or something else.” Reedy says. “Experimenting with this new medium taught me that artists, like everyone else, are not just one thing.”

Meet the artists participating in the 2017 Senior Thesis Exhibition:

+Abigail Abbott

Abbott’s series of still-lifes of vases of dried sunflowers evolved last semester from the sketches of the flowers she completed every day for a month. Over time she introduced new variables to the subject — different vases, tables, backgrounds, and lighting. “With every painting I finished, I was able to see elements I could not see before,” Abbott says.

As she experimented with the elements of her paintings through the academic year, the resulting changes “offer a unique visual representation of my struggle and progress over time.” And, Abbott notes, she found herself “moving towards abstraction organically, without consciously deciding to.”

+Hanna Bayer

Bayer’s paintings are physically large to emphasize the confidence, strength, and pain that many women carry with them. Inspired by the energetic physicality of art by Oskar Kokoschka, Ernst Kirchner, and Egon Schiele, Bayer makes work that asks to be connected with and questioned at an intense emotional level.

“Women’s bodies and minds are often separated by politicians, the media, and businesses,” Bayer says. “The body is seen as a marketable and malleable object, and the mind, emotion, and humanity are discarded. By creating disjointed panels where the body and the head are not united, I hope to create an obvious tension that speaks to some of that.”

“They Don’t See Me” No. 3 (detail), oil and oil pastel on fragments of theater sets, by Hanna Bayer.

+Alyssa Dole

Dole wanted to make photographs of people and followed that interest to documentary photography and the work of artists like Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams. After a few months of photographing diverse people in different Lewiston neighborhoods, Dole realized she needed to focus her approach. Inspired by an image she made of a Somali shopkeeper, she decided to concentrate on the shops on Lisbon Street and their owners.

“Although I heard many interesting stories throughout this process, I decided that I would like my photographs to stand by themselves rather than be accompanied by text,” Dole says. “I hope that my images can tell a story on their own.”

+Thomas Garone

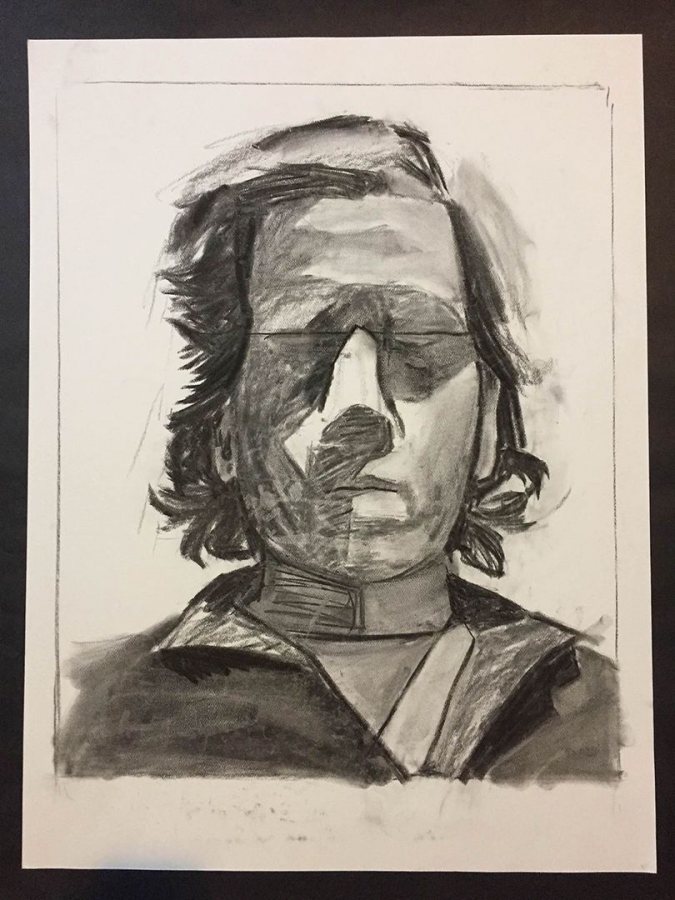

Garone has always gravitated to drawing, finding that the act of drawing “allows me to clear my mind and take some time for myself.” His preferred medium is charcoal, in part because it’s versatile and easy to revise — while allowing viewers access to the history of his revisions, in the form of previous marks that couldn’t be completely erased.

Garone maintains a looseness in his work that, he says, “reminds me to never take myself too seriously….I am not afraid to be critical about the work that I am doing.” Drawing “requires a lot of prior thinking, analysis, and a willingness to start over,” he says, “and by leaving evidence of my process it allows the viewers to see my struggle…making art.”

+Oskar Hall

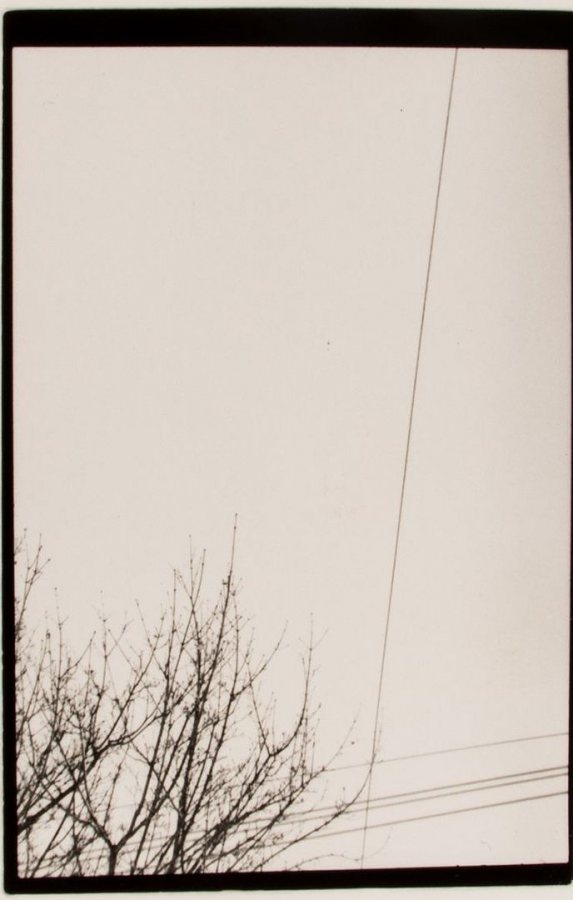

Hall shoots with an analog camera using black-and-white film. He says, “I want to return to photography’s roots, showing it as a physical process, something more than just a simple image.” His subject is utility cables, the telephone, television, and electrical wiring that’s ubiquitous in the streetscape.

Hall looks for “beauty and different forms in something that has become mundane in today’s world. There is something special about the graphic qualities of these tangled and sporadic wires.” While he conceives of his images as abstractions, Hall composes for the full frame and doesn’t apply any digital manipulation to his images. “I want to be intentional with each photograph I take and each print I make,” he says.

+Cuyler Hedlund

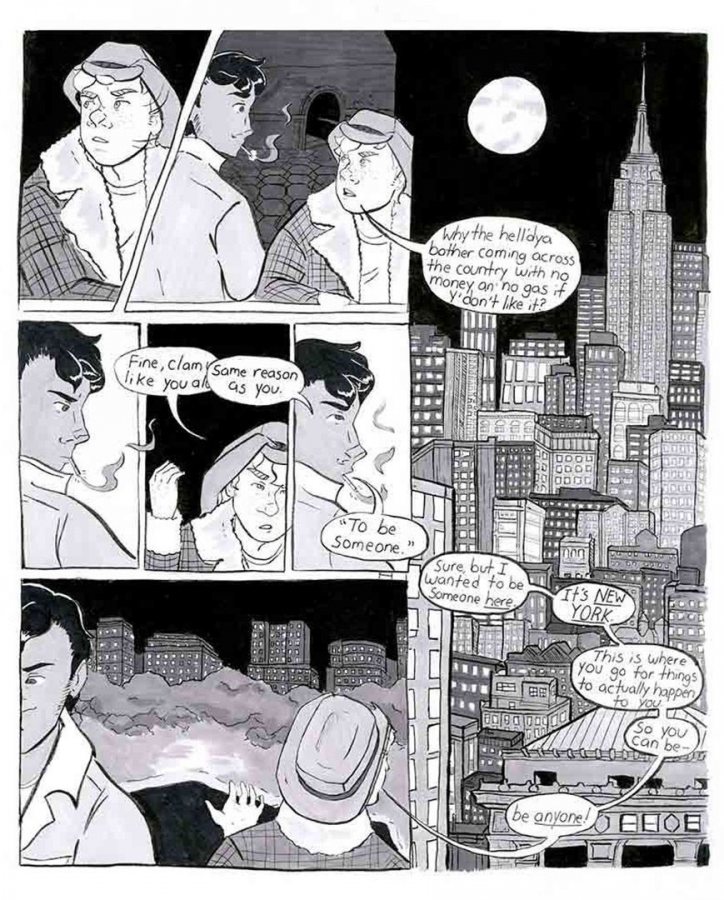

Hedlund made graphic-novel panels that both evoke and reconcile the deterioration and cultural vibrancy that defined New York City in the 1970s. Her protagonist is a stranger whose reactions to New York swing between extremes of infatuation and disgust. The graphic-novel medium, she believes, provides “an ideal marriage between visual and written communication,” Hedlund says. “I wanted to experiment with a medium that emphasized expression, body language, and backgrounds as integral to storytelling.”

She adds, “Working in stages of rough sketch to detailed sketch and then to inked page afforded me a sense of freedom to experiment and let the process of making marks inform the product.”

A selection from “The Only Living Boy in New York” by Cuyler Hedlund, in pen and permanent marker on Bristol board.

+Jose Herrera

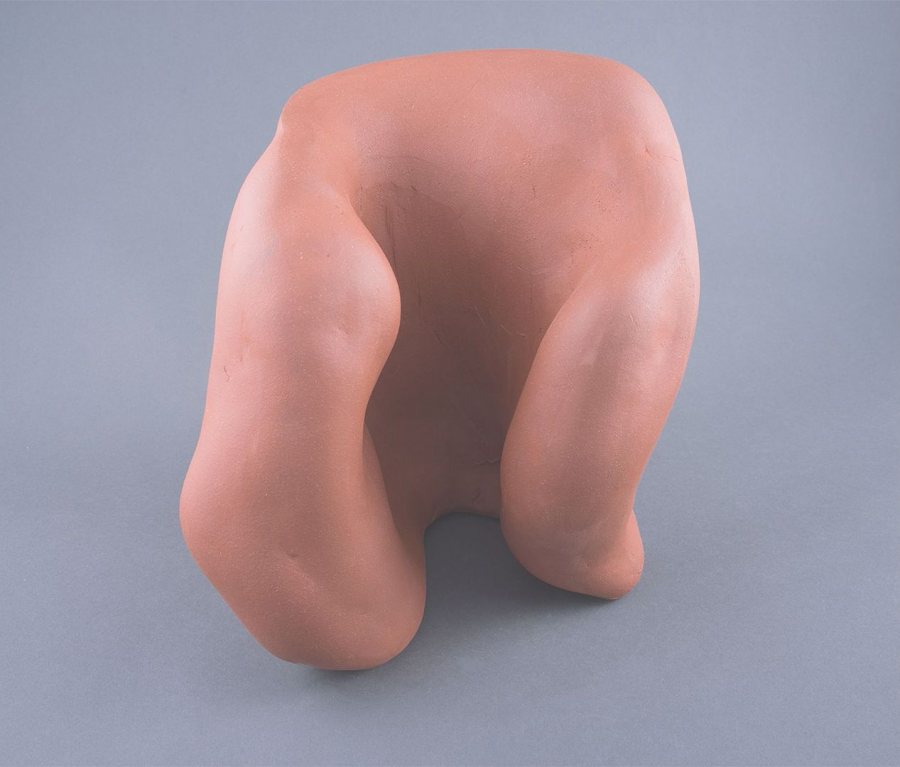

Herrera “came to art from a potter’s background: plates, cups, teapots, vases, and pitchers,” he says. In 2015, feeling constrained by the expressive conventions of functional pottery, he turned to making sculpture, adopting a minimalist approach.

More recently, he says, sculpture “has taught me that we understand the world through our bodies and as a result we usually bring bodily references to art. Making pieces that are “silent, sensual, active, united, and monumental,” Herrera embraces contradictions within the work. “Some of my pieces evoke stillness, while others evoke action, some share both qualities,” he says. “Some pieces are rough, while others appear to have a skin stretched over them. But they all are part of the same body of work.”

+Colin Moller

Moller’s frustration with the representational nature of photography inspired his thesis project. “Unlike in painting where you can construct non-referentially,” he says, “photography is limited to repurposing that which is already present in the world.”

Moller experimented with different approaches to making abstract photography until he recalled that “at its very essence, a photograph is simply a record of light”; unlike painting, where trying to represent light is a primary challenge, photography “enables the direct rendering of light.” Using a single source of light and various types of glass in stacked sequences, Moller created abstract compositions that he photographed.

+John Neufeld

Neufeld’s film photography turns away from today’s “enhanced, airbrushed, and heavily edited images” to emulate the “natural analog images of the past,” he says. “Photos without heavy manipulation are powerful because they are authentic and pure.” At the same time, though, Neufeld’s work “focuses on altering perception and creating the illusion of depth in a two-dimensional medium through the use of reflections.”

He adds, “I am inspired by Lee Friedlander. His images are full of information and demand the full attention of the viewer in order to understand what is going on in the photograph….Friedlander has shown me how an image can make people stop what they are doing and think.”

+Joan Oates

Oates says that color “is the driving factor in my current work. The complex relationships between different colors, shapes, and surfaces truly engage me.” She incorporates multiple canvases into a single piece and works quickly, applying large streaks of bright color with a palette knife. She typically works directly, reacting to the marks that she makes on the canvas, and often reworks her pieces intensively.

“I leave the work rough, exposed, and sometimes warped,” says Oates, who claims artists Gerhard Richter and especially Clyfford Still as inspirations. “But that is me inviting the viewer to see the physical work and, I hope, to experience some of the emotion I put into the paintings.”

+Deshun Peoples

Peoples makes functional porcelain whose colors, he explains, “are either pale and subtle or bright and bold.” His ceramics are inspired and influenced by the elegant, sophisticated, and timeless beauty of Chinese Song, Yuan and Qing Dynasty porcelains. Peoples believes that curves are essential to his art, explaining that curves “relate to how I see myself physically, and at its best, a beautiful pot with round, continuous curves is an extension of me.”

He adds, “I’m also interested in juxtaposing blocks of intense colors to create mosaic surfaces on my pots. When I use bright colors and non-traditional surface treatments, I’m trying to marry this source material to a more contemporary commercial ceramic industry.”

+Ashley Pollack

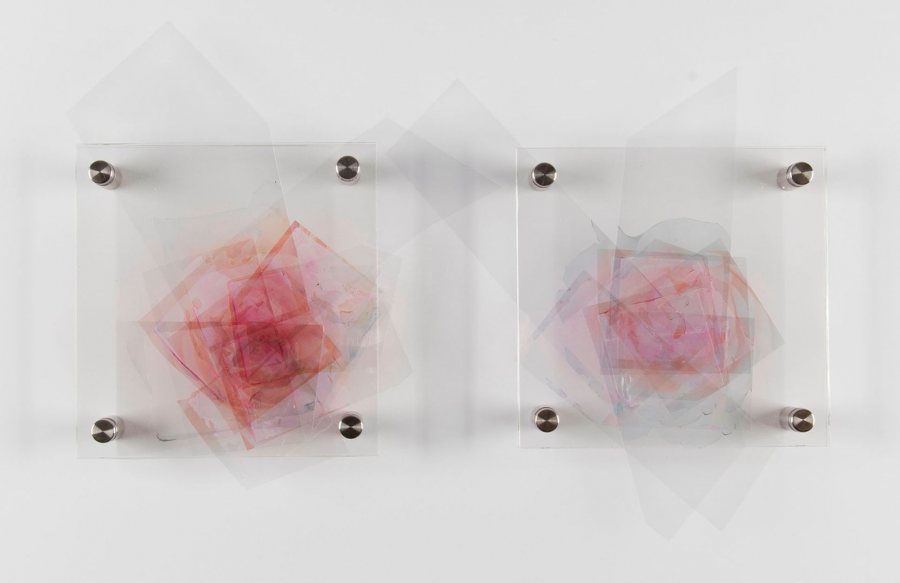

Pollack made collages from original photographs, inkjet-printed on transfer film — chosen for its “flexibility, color retention, and subtle but noticeable reflectivity,” she says — then she disassembled and reassembled them, and presented them on mounts including transparent acrylic sheets.

Working with flowers allowed her to explore a “dichotomy between a beauty informed by delicacy and the freakish quality that I associate strongly with orchids, but see in all flowers,” Pollack says. “When looking at my work, you are, invariably, also looking at yourself because of the reflectivity. I hope that this encourages viewers to have a personal and emotional response to their relationships with abstract ideas about the body, beauty and aversion.”

“Rosaceae,” a 2017 piece by Ashley Pollack, is a diptych made from inkjet prints on transparency film, acrylic sheets, and stainless steel standoffs.

+Calvin Reedy

Reedy received his first camera, a Polaroid, at the age of 5 as a gift from his father. “With that camera,” he says, “I grew up learning how to communicate through imagery.”

The purpose of this body of photographs, he explains, is “to counter America’s narrative about black men — a narrative that is hyper-masculine and untrue — and to also counter the images that dehumanize and perpetuate violence against the black body. My vision for this body of work is to re-contextualize, re-frame, and re-present notions of black masculinity.” Reedy seeks to rewrite the mainstream narrative of black masculinity through his depictions of “friendship, brotherhood, intimacy, and love.”

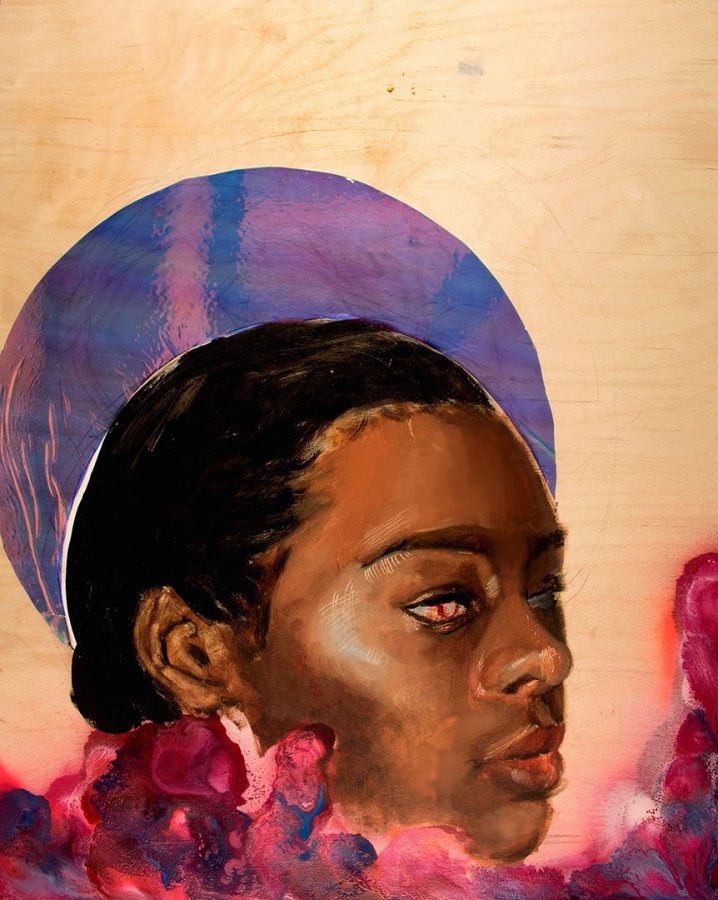

+Mary Grace Schwalbe

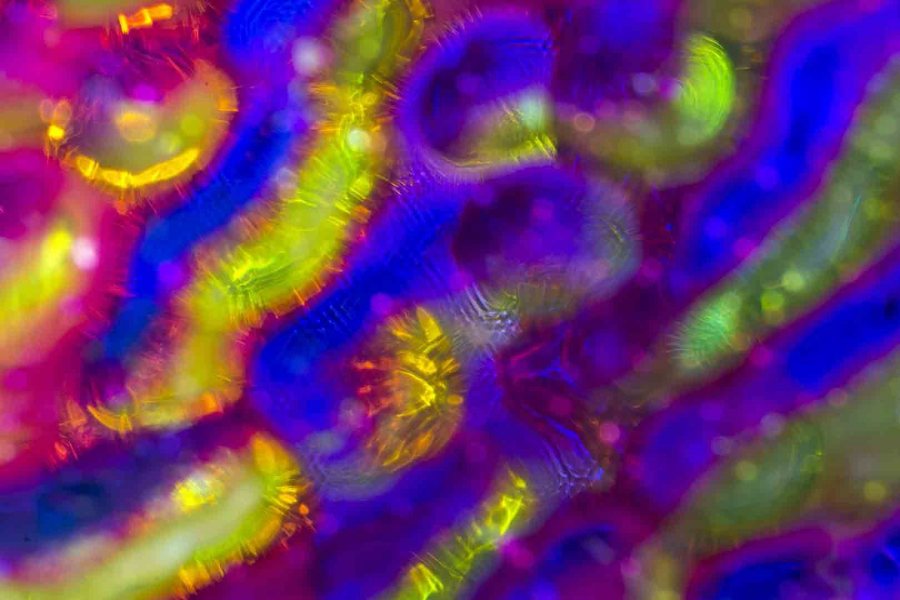

Schwalbe makes paintings and drawings that explore and challenge historical portrayals of beauty and womanhood. “Women are expected to suffer separately from men — and in silence,” she says. She employs bright, caustic colors and medical images — based on medical stock photos and slides of tissue samples or bacteria — to reveal the beauty in “what might initially be grotesque or horrifying.”

In short, Schwalbe wants to deepen her viewers’ conceptions of what “beautiful” may entail. “Beauty can often be aesthetic but it permeates deeply through the surface of its subject eliciting a feeling of both awe and fear,” she says. “To me, beauty is terrifying, powerful, and far beyond our control.”

“Fibrosis” is a 2017 image by Mary Grace Schwalbe in oil, spray paint, and dichroic film on birch panel.

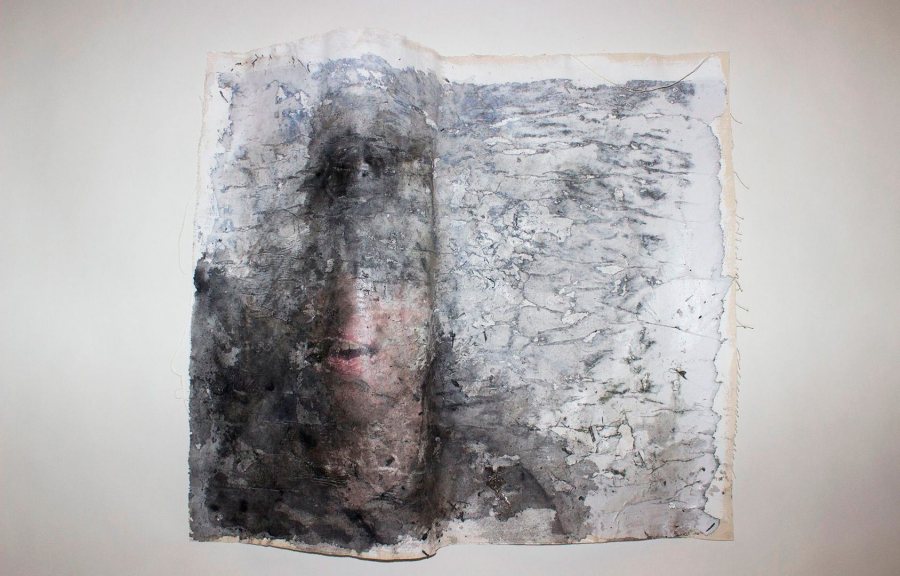

+Erin Shea

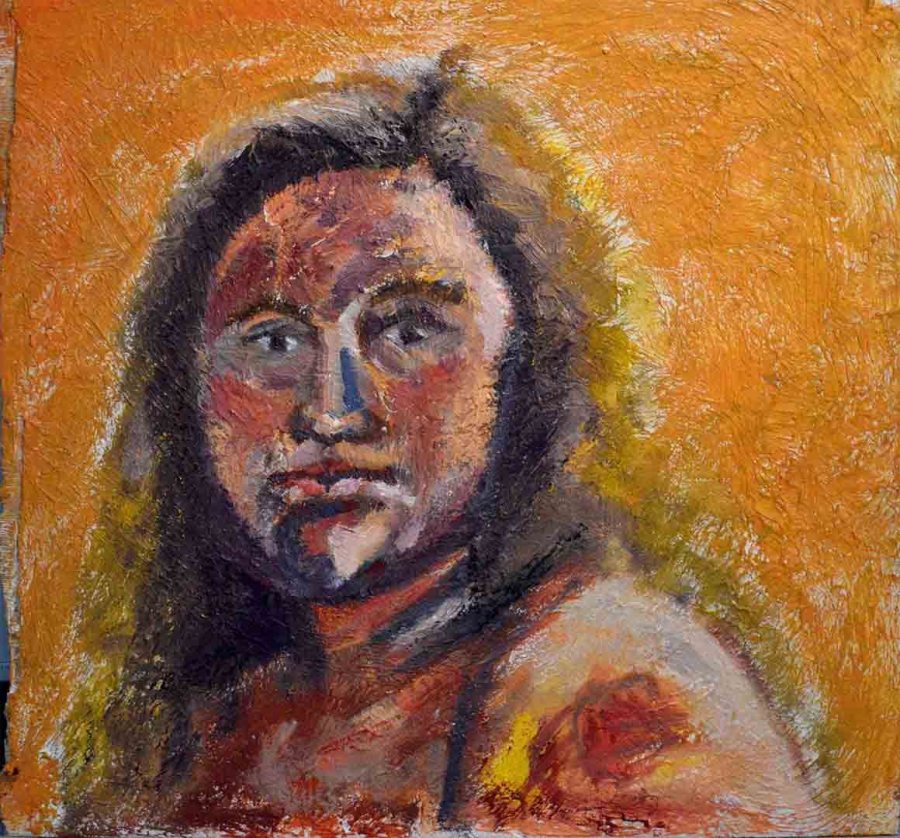

Shea paints portraits that seek to challenge the carefully curated, polished personas that people project on social media such as Facebook. “While people often display themselves in an idealistic way, that is not what is happening here,” she says. Using herself and her peers as subjects, she isolates “each individual from the outside world, trying to make very physical paintings that read as emotional objects.”

She transforms the two-dimensionality of a photograph into a physical three-dimensional object, and converts her subjects’ “faces and surface expressions so that they are no longer recognizable as individuals” — hoping to uncover the individual’s raw emotions and personality.

An untitled work from 2017 made by Erin Shea from collaged paper, transfer printing, watercolor, gesso, and varnish on canvas.

+Hannah Tardie

Tardie constructs sculptures that have a formal connection to the body. These connections that are established are due in large part to the materials that she uses such as women’s socks and tights. “I’m curious about the interaction between gender performance and body parts, and the connotation of body parts as gendered,” she says.

Tardie implies strictures of gender by manipulating or distorting her materials “to produce objects that read as exaggerated and even mutilated bodies.” She adds, “the success of the sculpture will be entirely dependent on viewers’ own bodily interactions with it . . . I want people to be aware of their bodies in space when they view the work.”

+Jackson Whitehouse

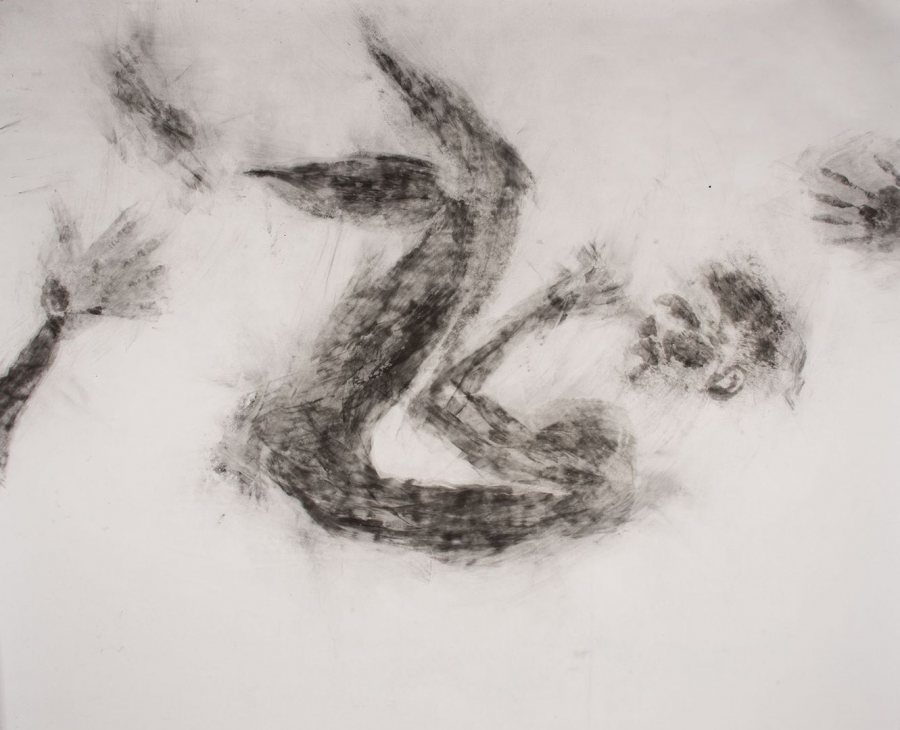

Whitehouse uses his body to make prints directly onto on paper. He prints with media such as charcoal powder and black skin-safe paint, as well as with vegetable oil, which changes the light-transmitting quality of the paper in affecting ways.

The prints are “my fear, my vulnerability, my body, and my shame, all represented outside myself,” he says. “The most successful prints look as if they were made effortlessly, and almost as if they occurred naturally on the paper, but the process of making them is always physically challenging,” he explains. “Since there is nearly no erasing the marks I make, the act of printing is high-stakes; one slip or accidental graze of my paint-covered hand and I have to start over from scratch.”