Bates has announced faculty promotions, including tenure awards and full professorships, effective for the 2017–18 academic year.

“Our newly tenured and promoted faculty are exemplars of the scholar-teacher-mentor ideal,” said Matthew Auer, vice president for academic affairs and dean of the faculty. “They are leaders in their disciplines, deeply engaged in our community, and focused on the success of their students with sincerity and purpose.”

Recommended by the faculty’s Committee on Personnel and approved by the Bates College Board of Trustees, the promotions have been awarded to faculty members in the fields of education, French and francophone studies, history, neuroscience, politics, and psychology.

Meet the seven newly promoted professors, learn their research fields, and discover why they teach:

Promotions to associate professor with tenure

+Jason Castro

Department: Neuroscience

Appointment year: 2012

Doctoral institution: University of Pittsburgh

Fields of research: Sensory systems, olfaction, electrophysiology, neuro-informatics

Why I teach:

I really feel like I’m in the presence of a profound but knowable mystery when I think about the brain and behavior. Teaching is basically my way of connecting with kindred spirits over these things.

I love the hard work of trying to understand things clearly and the challenge of reducing ideas to their essentials so they can be shared honestly and critically. I can’t think of anything more rewarding than knowing that I’ve inspired someone to also find these pursuits valuable. I get to try my hand at this every day, in the company of students who are kind, generous, and brilliant.

Jason Castro has been promoted to associate professor of neuroscience at Bates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

+Caroline Shaw

Department: History

Year of appointment: 2010

Doctoral institution: University of California, Berkeley

Fields of research: Histories of Britain and Europe in the world, in particular histories of modern rights, liberalism, and humanitarianism through the lenses of slavery and abolition, refugee crises, and personal reputation

Why I teach:

One of my beloved mentors, now passed away, insisted that to engage with ideas and to really study the past, one has to do so in conversation and, preferably, over a meal. She had a way of making even the most stressful of moments in a graduate student’s life — studying for comprehensive exams — engaging and, dare I say it, fun.

As a researcher, writer, and student, I can get lost in the detail, often happily. But it is in sharing that work and in investigating the voices of the past with others that I gain better perspective. Teaching is for me an extension of that process and a way of enabling my students to do the same.

Caroline Shaw has been promoted to associate professor of history at Bates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

+Mara Tieken

Department: Education

Year of appointment: 2011

Doctoral institution: Harvard University

Fields of research: Rural education, college access and persistence, community organizing, race and class in rural communities

Why I teach:

I have always been a teacher. I have taught pre-schoolers, elementary schoolers, middle schoolers, graduate students, adults seeking their GED, and now, undergraduates. I don’t think I could not teach.

I love teaching. I love the challenge of figuring how to make a difficult, abstract concept — like school funding or critical race theory — accessible and relevant. I love the relationships that emerge from wandering together into new territory and unexplored topics. I love the anger students feel towards the world’s educational injustices and their passion for doing something about those injustices. Teaching keeps me engaged and hopeful.

The opportunity to teach is a privilege, and I feel very lucky to teach at Bates.

Mara Tieken has been promoted to associate professor of education at Bates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Promotions to full professor

+Áslaug Ásgeirsdóttir

Department: Politics

Year of appointment: 2001

Doctoral institution: Washington University

Fields of research: Conflict and cooperation over fisheries, ocean governance, settlement of maritime boundaries, climate change and oceans, marine spatial planning, Law of the Sea

Why I teach:

At Bates, I have the privilege to teach students who are curious about the world around them and who are willing to take classes covering topics they do not know much about. Ocean governance is one such class. Studying the ocean and its management allows students to explore the complexity of governance in all its messiness.

My favorite moment is always when they realize that no one policy works for everyone, and that grappling with how to fairly distribute common-pool resources is difficult and time-consuming. Given that most of the students know little about the challenges facing our oceans before they sign up, I find that they are freer to think creatively about the link between politics and economics, peoples and oceans, fairness and future challenges.

Áslaug Ásgeirsdóttir has been promoted to professor of politics at Bates. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

+Helen Boucher

Department: Psychology

Year of appointment: 2005

Doctoral institution: University of California, Berkeley

Fields of research: Self-concept, self-esteem, self-regulation, social psychology, cultural psychology, positive psychology

Why I teach:

One of my great joys of teaching psychology is to get students thinking about how psychological concepts and findings operate in their daily lives. So much of what we do is governed by habit and a lack of reflection, but psychology offers students a wonderful opportunity to carefully and critically think about the causes and consequences of their own and others’ behavior.

I love it when we are discussing some psychological theory and I look around and see the knowing nods, smiles, and exchanged glances that signal that sense of “Ah yes, that has happened to me, too.”

One of my other great joys is guiding students as they use their own research to contribute to psychological knowledge. This can be a frustrating struggle at times as students gain expertise and offer, at first, tentative hypotheses. But it is truly exhilarating to see them gain confidence not only in what they have learned but also in acknowledging what they still don’t know about their topic.

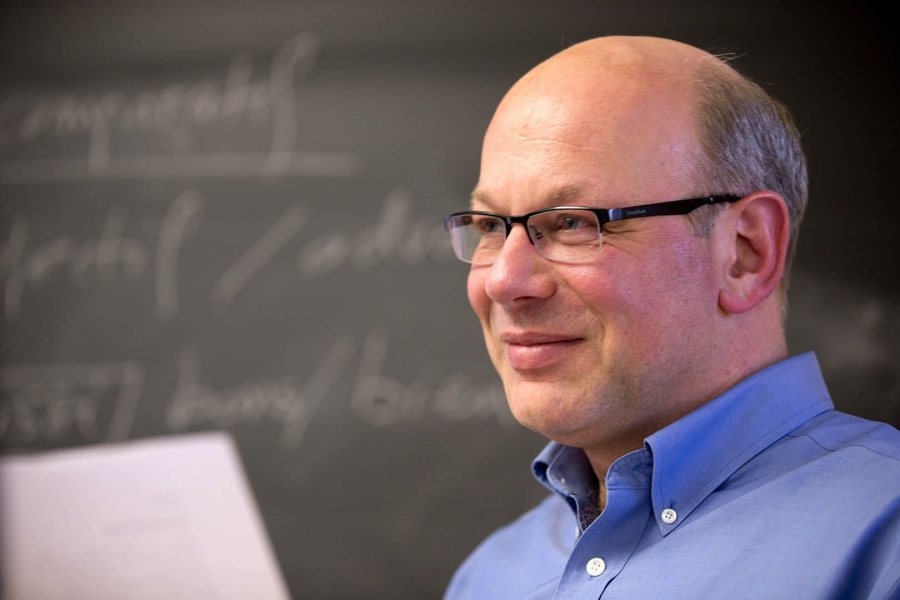

+Alex Dauge-Roth

Department: French and Francophone Studies

Year of appointment: 2005

Doctoral institution: University of Michigan

Fields of research: Literary and cinematic representation of violence, genocide studies, AIDS literature, autobiography and testimony as genre, identity politics and immigration

Why I teach:

If learning and speaking a foreign language already represents a first departure from one’s original identity and a step toward others, the intellectual journey I invite my students to take is not only linguistic.

My courses favor works from authors, filmmakers, and characters who come from cultural and existential backgrounds that differ from my own and those of my students. They introduce a diverse spectrum of values, norms, expectations, and trajectories that challenge how we think about identity and define forms of social belonging.

With my students, as we study the historical and cultural diversity of the francophone world, we engage with others’ worldviews to understand how others shape and transform the complex fabric of a given society.

This critical analysis fosters multiple viewpoints, challenges assumptions, and purposefully connects analytical thinking with life experiences and ethical choices for all of us — and it drives my teaching.

Alex Dauge-Roth has been promoted to professor of French and francophone studies at Bates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

+Karen Melvin

Department: History

Doctoral institution: University of California, Berkeley

Year of appointment: 2005

Fields of research: Colonial Mexico, early modern Catholic world, history of religion, urban history

Why I teach:

I see teaching as a collaborative effort to better understand the world. The study of history gives depth to our current set of affairs, helping us see how we got here, who we have been, and, with any luck, a sense of why this particular present might have emerged from that past.

At the same time, history also allows us glimpses, however fleeting, of worlds different from, and perhaps completely unconnected to, our own. Delving into these strange places and taking seriously the task of understanding how people who lived in other times and places saw their world helps us manage our own complicated and culturally plural world.

More specifically, I teach Latin American history because I want students to discover the region’s wide range of histories and cultures. Too often what we see and hear about these peoples and places is shaped by images and rhetoric that come out of political debate or sensationalist media accounts rather than informed study.