Monuments to Confederate leaders celebrate white supremacy and should be removed from public spaces, participants in a Bates panel agreed Monday night.

But removing such monuments would mean little without an understanding of why they were created, how racism persists today, and how to move forward.

“The value of history in relation to these debates is just as much about absence as it is about presence,” said Andrew Baker, a lecturer in history and Mellon Diversity and Faculty Renewal Postdoctoral Fellow.

The panel discussion, which filled a room in Pettengill Hall, was held to shed light on issues of white supremacy and Confederate monuments in the wake of violence in Charlottesville, Va. It was sponsored by the Department of History and the Office of Equity and Diversity and moderated by Christopher Petrella ’06, lecturer in humanities and associate director of programs at the OED.

Extra chairs were needed for Bates community members who attended “Responding to Charlottesville: Historical Perspectives,” a panel discussion on fighting racism, Confederate monuments, and activism in academics. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

The wide-ranging discussion encompassed the historical and geographic context of Confederate monuments and the intersection of anti-racist activism and academia, as well as issues of activism on social media and the role of violence in protests.

Baker said focusing only on Confederate monuments risks forgetting that racism and white supremacy were not unique to the South in the 19th century. In fact, monuments to Confederate leaders were erected in the early 20th century, partly in reaction to an emerging civil rights movement.

For their part, Northerners were complicit in advancing white supremacy, both before and after the Civil War, Baker said. For example, 20th-century historians whose work sought to legitimize the idea that slavery was positive and black suffrage negative were not primarily from Southern institutions, he said.

Racism has “always been a part of America itself, and so that touches all of us,” said Lecturer in History Andrew Baker. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

It is important, therefore, not only to remove Confederate monuments, but to look at history closer to home, Baker said — at, for example, Benjamin Bates, who made his fortune in Maine selling clothing made from slave-grown cotton and later gave some of that fortune to namesake Bates College.

People who live anywhere with a difficult racial history “generally like to say that it belonged to a different time,” Baker said. “I think we need to address that lie head on and recognize that these problems are everywhere, it’s always been a part of America itself, and so that touches all of us.”

Creating and focusing on Confederate monuments, added history department chair Margaret Creighton, meant that other stories from the Civil War are left behind. She recalled how, during fieldwork in Gettysburg, Pa., she and her students met an African American woman whose ancestors had lived in the town during the Civil War and either suffered under or fought against Confederate soldiers.

Professor of History Margaret Creighton said the presence of Confederate monuments ignores other people’s stories from the Civil War. “Their history was never written.” (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“We can talk all we want about the issue of erasing monuments, but there are many people for whom monuments were never built,” Creighton said. “Their history was never written. Filmmakers never made a documentary about them.”

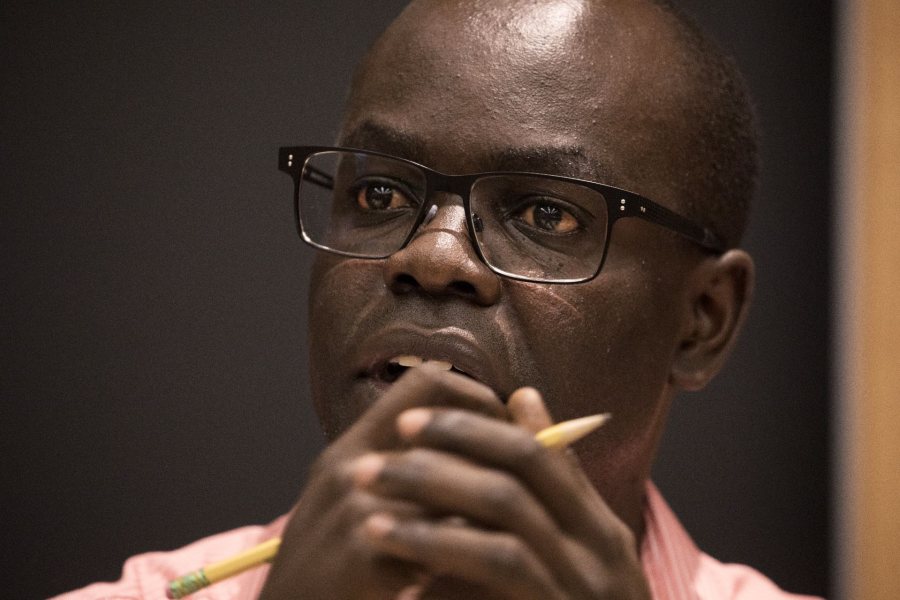

Assistant Professor of History Patrick Otim, meanwhile, placed Confederate monuments in a global context. Otim said his native Uganda and other African countries are experiencing a similar conflict over their own set of monuments — ones that celebrate both European colonial powers and the dictators who took power in some countries after independence.

Africans, he said, are paying attention to the American debate.

“It will inform the sort of discussions that are going on in different African countries,” he said. “What goes on here, because of the power of the Internet or access to information in different parts of the world, will dictate what goes on in different African countries.”

As the discussion continued, a question emerged: How can professional historians and academics fight racism, when its negative effects seem so immediate?

Assistant Professor of History Patrick Otim said similar debates over monuments are happening in African countries, including his native Uganda. “What goes on here…will dictate what goes on in different African countries,” he said. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Panelist Robin McDowell has experience in both fields: She is a doctoral candidate in African and African American studies at Harvard who also works in a group that fights to take down symbols of white supremacy in New Orleans. McDowell said activism and academia do not have to be separate — the organizers she works with have many roles, including as researchers.

The organization, Take ’Em Down NOLA, uses the fight for monument removal as a way to push toward broader racial and economic justice.

Discussing monuments as well as subtler forms of racism can be an effective way to build a coalition, McDowell said.

“That’s their access point, to start having conversations and start understanding,” she said.

But if Confederate monuments are removed, what to do with them afterwards is a complicated question. Audience member Mia Yinxing Liu, an art historian and assistant professor of Asian studies, said she wanted Confederate monuments to be removed from public spaces but asked the panel whether statues could be studied as art history.

Robin McDowell, a Harvard doctoral student and community organizer, said working to remove monuments can be a starting point for addressing systemic racism. “We can’t underestimate the imagination of our communities,” she said. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“We [art historians] are supposed to be the ones who know who sponsored them, what places they are in. We are supposed to think about those issues,” she said.

Baker said he generally did not want to see Confederate statues in museums but thought art historians could work to dismantle the message of Confederate statues.

“It’s a very subtle and interesting way of reflecting on how we can repurpose these monuments, maybe in ways that wouldn’t occur to the average person,” he replied. “The art historian would think carefully about how to subvert their own purpose, the reason they were put up to begin with.”

A related question emerged: What, if anything, should replace a vanquished monument?

McDowell said implementing a new vision had to involve the people such a vision would affect. In New Orleans, she said, more than 200 local artists recently met to propose replacements for white supremacist monuments in the city.

“We can’t underestimate the imagination of our communities,” she said.