As a Bates student, Brenna Callahan ’15 helped run a literacy program at Montello School, a Lewiston elementary school about a mile from campus. That work often involved reading to the pupils.

One day Callahan read the picture book Nabeel’s New Pants: An Eid Tale to a Muslim child.

It was the first time that he had seen a book about that Islamic holiday, says Callahan. “He saw himself in that book in a way he hadn’t before. And that was powerful.”

There is considerable power in children’s books. It’s a formative power, especially in the case of picture books for younger children, with their rapidly developing intellects and personalities.

So what’s the formative impact on children of color when most picture books — as many as 90 percent — are all about white people? And if you want to lay hands on one of the relatively few books that feature diverse characters, what happens when the local library catalog can’t help you find them? And what if that library doesn’t even know which races or cultures are represented in its children’s book collection?

Krista Aronson, associate professor of psychology at Bates, has devoted considerable time and thought to such questions. And she has an answer.

As part of a team including Callahan, Bates humanities librarian Christina Bell, and noted children’s author-illustrator Anne Sibley O’Brien, Aronson has created the Diverse BookFinder project: a three-fold set of resources that bring new accessibility to the world of diverse children’s books:

- First, there’s the Picture Book Collection, a comprehensive physical collection of some 2,000 diverse books. Housed at Bates’ George and Helen Ladd Library, the collection is nationally unique in that the books are available for anyone to sign out.

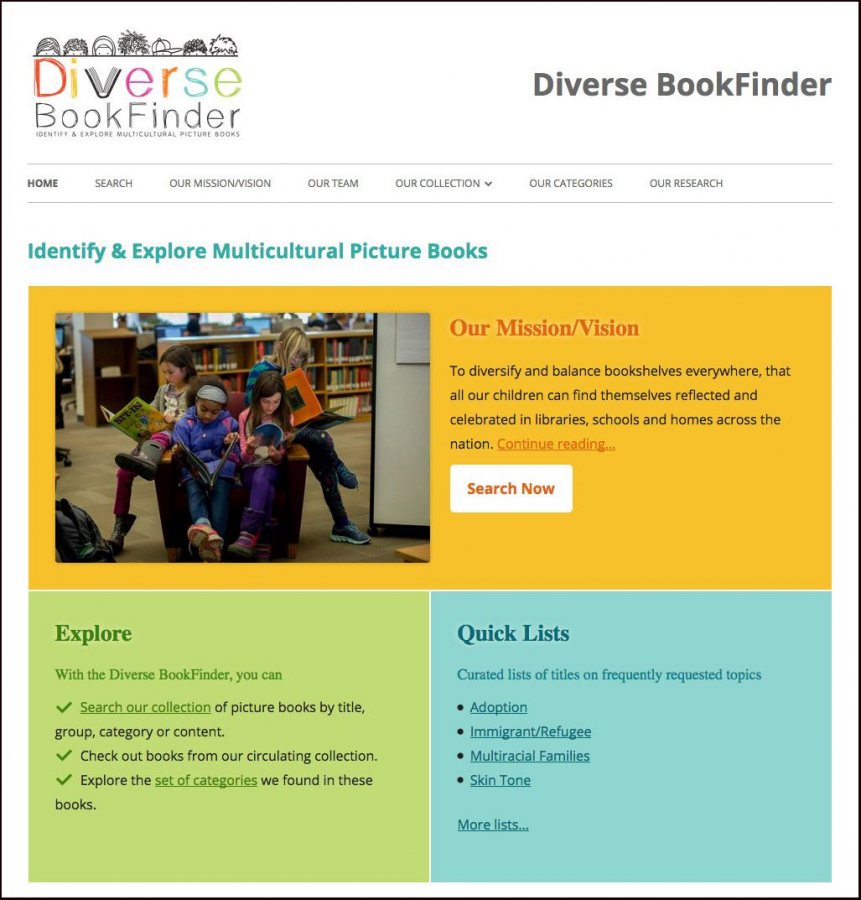

- Second is the Diverse BookFinder itself, a public database that went live this week. Designed to mirror the ever-growing Picture Book Collection, the DBF makes — for the first time — diverse picture books findable by both the human characteristics and, importantly, narrative messages that recur in them.

- Third is an analytical method, based on the Diverse BookFinder resources, that will enable librarians and other book curators to understand how diversity is represented in their own picture book collections.

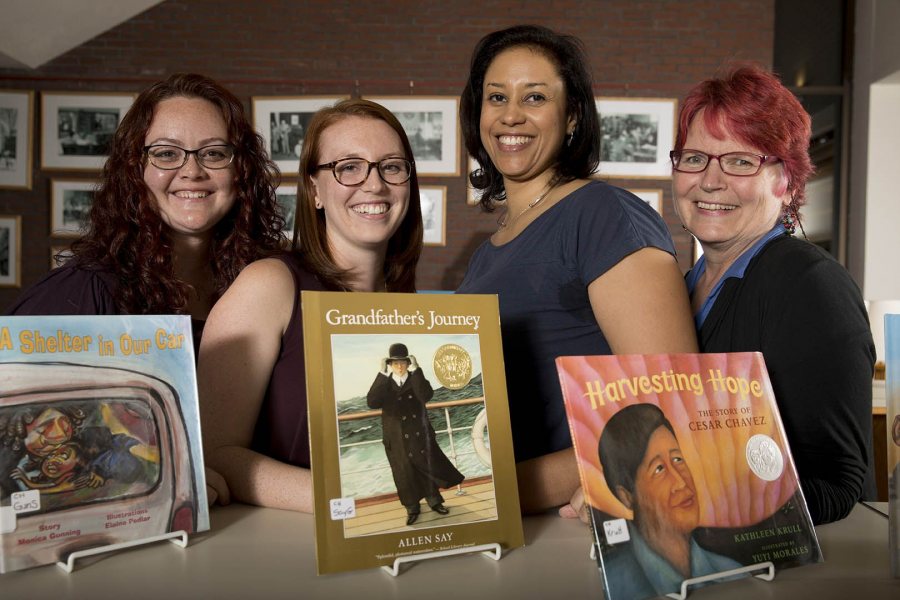

The team behind the Diverse BookFinder project: from left, Christina Bell, humanities librarian; Brenna Callahan ’15, Maine Campus Compact civic leadership post-baccalaureate fellow; Krista Aronson, associate professor of psychology; and Anne Sibley O’Brien, author and illustrator. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The Diverse BookFinder project, which recently received a grant of $250,000 from the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services, is a “potential game-changer” for parents, librarians, and teachers — anyone seeking diverse children’s books, says Cheryl Klein, a member of the Bates project’s advisory board and the editorial director for Lee and Low Books, which specializes in multicultural children’s titles.

Book learning

Aronson, who is biracial, studies how people, particularly the young, come to understand social constructs like race, and how such understanding affects interactions and psychological well-being.

Her dissertation at the University of Michigan focused on identity development among African American teenagers and the role that parents play in the socialization process. The size of the black community in Ann Arbor ensured she’d have a substantial pool of research subjects.

But when Aronson joined the Bates faculty, in 2003, that meant a move to the nation’s whitest state and therefore different directions for her research. The inspiration for one new direction came from one of her daughters, Sophia, and Sophia’s relationships with white and Somali children at school.

When Sophia was about 6, “she was bringing home difficult questions around the topics of race and immigration that she was being asked by her friends,” says Aronson, “which gave me insight into some of the issues they were grappling with.”

For Krista Aronson, an inspiration for a new direction for her research came from her daughter’s relationships with white and Somali children at school. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Aronson discovered psychological research in England exploring how picture books affect children’s attitudes towards refugee children. Experiments had shown that when children take in stories about different groups of children getting along well, they in turn tend to get along better with peers who are different from them.

Collaborating with Rupert Brown, a prominent social psychologist who studies prejudice and stereotyping, Aronson sought to follow up on and localize that prior research by studying children’s responses to books portraying interactions between white and Somali children in Lewiston.

But no such children’s books existed. So one of Aronson’s thesis students, Elizabeth Ellman ’10, created stories under the guidance of two Mainers known for making diverse children’s books, writer Margy Burns Knight and illustrator-writer Anne Sibley O’Brien. O’Brien illustrated the stories for the research.

“These books mattered. They could actually shift children’s perceptions.”

Conducted in winter 2010 with support from the college’s Harward Center, Aronson’s experiment confirmed that so-called cross-group picture books can indeed promote better relationships among diverse kids. “It was a wonderful learning experience for me and my students, and the community,” Aronson says. She and O’Brien went on to give a series of public workshops on the study.

Raised in South Korea by white American medical missionaries, and deeply impressed by her experiences there, O’Brien has made it her mission to use children’s literature, as she says, to “explore and celebrate human difference.” She has illustrated 32 children’s books and written 14 of those books, including I’m New Here, a picture book about immigrant children that was a Kirkus Reviews Best Book of 2015.

Author and illustrator Anne Sibley O’Brien talks about the Picture Book Collection in Ladd Library during the college’s 2017 Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“The work with Krista was like, ‘Eureka!’” O’Brien says, because it provided “data that proved what I was betting on: that these books mattered that much, and that they could actually shift children’s perceptions.”

That early work, Aronson says, “got me thinking about picture books more broadly. I wanted to see what we could do with the books that are out there.” And, she wondered, “What is out there?’

“And that’s how Annie and I started collecting the picture books.”

First up: the Picture Book Collection

For both Ladd Library and the team that created the library’s Picture Book Collection, “it was an early decision that we needed to make this usable for as many people as possible,” says the library’s Christina Bell.

From Aronson’s perspective, as a researcher seeking to translate her work for the public, “it’s important that these books don’t just sit in my lab and get utilized when I teach, or pulled off the shelf to analyze and then shoved back on there. I want my work to have meaning beyond, perhaps, the scholarly or the academic.”

The fact that the books of the Picture Book Collection circulate makes the collection nationally unique. Collections of diverse children’s books are not unheard of, but access to them is restricted. Books in the Bates collection, on the other hand, may be checked out in person by anyone with a Bates ID or Ladd courtesy card, or remotely via interlibrary loan.

If access to the collection is straightforward, building the collection was anything but. “When we started this project I had no idea that it was going to be so difficult,” Aronson says.

The paucity of books depicting people of color is “a crisis for all of our children.”

For one thing, diverse picture books continue to constitute a small fraction of all children’s titles. Ten to 14 percent of picture books that are published annually feature people of color, “and that number has not budged since the late 1960s,” Aronson says.

Yet, even as the proportion of diverse children’s books hasn’t budged, the proportion of diverse children has blossomed in the U.S., as O’Brien points out. The paucity of books depicting people of color, she says, is “a crisis for all of our children, because it’s not healthy or useful for white children to only see reflections of themselves,” or for children of color not to see themselves in books.

“It doesn’t help build relationships, and it doesn’t help them function in the world that they’re entering.”

The Bates team’s book search led them to 111 publisher websites plus online resources including the I’m Your Neighbor website; online lists of titles, including World Full of Color; the database of Baker and Taylor, an important book distributor; and a list provided by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, the site of a major diverse book collection at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The search is a dynamic, grassroots process. “I learn of new publishers all the time,” Aronson says, “and people bring titles to me,” including a parent whose daughter had worked on thesis with Aronson, and who, at Commencement, recommended a book that she proceeded to add.

Next: the Diverse BookFinder

The Bates team is taking its quest for picture book accessibility to a new plane with the online Diverse BookFinder. Because, after all, how valuable is a book that you can’t find?

The online Diverse BookFinder website allows users to search books by title, racial group depicted, where the story takes place, and the narrative message within.

If you go to your local library looking for multicultural picture books, it’s possible that the catalog won’t recognize the search terms that make most sense to you. Say you’re looking for The Sandwich Swap, a book about two best friends, one white and one Arab American, who have a falling-out over their lunches (peanut butter and jelly vs. hummus).

You might use a search term like “Arab American” to find it. And you would come up blank. In the catalogs of the Library of Congress and WorldCat, the word “Arab” does not appear in entries for The Sandwich Swap (whose author, by the way, is the queen of Jordan), although the book’s various subject headings do include “food habits.”

Traditional library cataloging doesn’t tend to indicate the race or ethnicity of the people in a book, Bell explains. “It will document in a line or so, very generally, what’s happening in the story, but there’s no indication of who is represented in the book.”

Even publishers themselves don’t necessarily make findable their own books featuring people of color. “It seems as though some, when they enter books, just don’t want to use any race, cultural, or ethnic labels,” Aronson says.

As they amassed the collection, Aronson, O’Brien, and Callahan identified and refined nine recurring categories that the DBF associates with diverse books.

The nine categories reflect various narrative messages that a given book is designed to convey. For example, “Cross Group” books like Anna McQuinn’s My Friend Jamal portray interactions of characters across racial or cultural difference, while “Any Child” books tell stories about characters of color where race, culture, or ethnicity are incidental to the plot.

+How the Diverse BookFinder makes book messages searchable

Nine narrative categories

More than a publicly searchable collection of diverse children’s books, the Diverse BookFinder also makes a book’s narrative messages searchable, thanks to a unique search language that include these nine narrative categories:

Any Child: Stories that depict characters of color but do not make race, ethnicity, or culture part of the plot. Any Child books can be identified as books whose characters’ race could be changed without changing the story line.

Any Child: Stories that depict characters of color but do not make race, ethnicity, or culture part of the plot. Any Child books can be identified as books whose characters’ race could be changed without changing the story line.

Example: Lola Reads to Leo by Anna McQuinn

Cross Group: Stories that portray interactions of named characters across racial or cultural difference, including those depicting same-age and cross-age friendships; the interactions depicted can be positive, negative, hostile, or ambiguous.

Cross Group: Stories that portray interactions of named characters across racial or cultural difference, including those depicting same-age and cross-age friendships; the interactions depicted can be positive, negative, hostile, or ambiguous.

Example: My Friend Jamal by Anna McQuinn

Beautiful Life: Stories about a particular racial or cultural group experience that take readers into the everyday world of characters in countries around the world, with specific cultural components such as language, food, celebrations, and traditions.

Beautiful Life: Stories about a particular racial or cultural group experience that take readers into the everyday world of characters in countries around the world, with specific cultural components such as language, food, celebrations, and traditions.

Examples: Hana Hashimoto, Sixth Violin by Chieri Uegaki; Red Kite, Blue Kite by Ji-li Jiang

Race/Culture Concepts: Books that explore and compare specific aspects of human difference, inviting children to consider new perspectives related to racial, ethnic, or cultural identity.

Race/Culture Concepts: Books that explore and compare specific aspects of human difference, inviting children to consider new perspectives related to racial, ethnic, or cultural identity.

Examples: Going to Mecca by Na’ima Robert; Shades of People by Shelley Rotner

Oppression: Stories of prejudice, mistreatment, and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, or culture, such as stories focused on slavery, the civil rights movement, or internment.

Oppression: Stories of prejudice, mistreatment, and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, or culture, such as stories focused on slavery, the civil rights movement, or internment.

Example: Hope’s Gift by Kelly Starling Lyons

Folklore: Myths, legends, folk, and fairy tales that are set in a particular cultural context, introducing readers to traditions, activities, languages, and values.

Folklore: Myths, legends, folk, and fairy tales that are set in a particular cultural context, introducing readers to traditions, activities, languages, and values.

Examples: The Orphan and the Polar Bear by Sakiasi Qaunaq; Beauty and the Beast by H. Chuku Lee

Biography: Nonfiction presentations, narrative or non-narrative, about the life of a particular person or group of people from a historical or contemporary perspective.

Biography: Nonfiction presentations, narrative or non-narrative, about the life of a particular person or group of people from a historical or contemporary perspective.

Example: Side by Side: The Story of Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez by Monica Brown

Incidental: Stories that depict a diverse group of non-primary characters, or books with a diverse cast of background characters and a white protagonist.

Incidental: Stories that depict a diverse group of non-primary characters, or books with a diverse cast of background characters and a white protagonist.

12 Days of New York by Tonya Bolden; Read All About It by Laura Bush and Jenna Bush Hager

Informational: Nonfiction books presenting factual information, with or without a storyline; may be encyclopedic. Diverse communities are depicted but culture is not always central to the content.

Informational: Nonfiction books presenting factual information, with or without a storyline; may be encyclopedic. Diverse communities are depicted but culture is not always central to the content.

Examples: The Good Garden: How One Family Went from Hunger to Having Enough by Katie Smith Milway

The team, supported during this phase of the project by library cataloging consultant Deborah Tomaras, also created other code sets that indicate where stories take place and what racial or cultural groups the characters represent. The racial-variables coding is unique to the DBF, and Brenna Callahan herself coded the collection’s first 600 books and then wrote about that work for her senior thesis, with Aronson as her adviser.

Deployed in tandem with existing finding aids, the DBF promises to “really help people just cut through to what they’re after — which is the Holy Grail of publishing,” says Klein of Lee and Low Books.

Interested in diverse children’s books through her literacy work with schoolchildren, interdisciplinary major Brenna Callahan ’15 made Diverse BookFinder research central to her senior thesis, with Krista Aronson as her adviser. Callahan is now an AmeriCorps VISTA Fellow at Bates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Alongside the Picture Book Collection and the Diverse BookFinder, the third piece of the project has been piloted and will be developed as funding becomes available: an online tool that can analyze a given collection of books for representational balance.

The same coding that helps individual users find a book or two via the DBF also allows wholesale analysis of a particular collection or grouping of books — in a library, say, or in a publisher’s new releases for a given year — to reveal what messages the collection is sending and how it might be improved.

“One library that we did this with,” Aronson says, “learned that 2.4 percent of their books featured human characters of color, and that 65 percent of this small proportion were African American characters” — though 19 percent of the population served by the library was Asian.

The messages within

On most Sundays, Aronson and her team members meet for tea and snacks, vetting new titles for the collection and plotting out objectives for the near- and longer terms.

Specifically, they’re pondering how or whether to represent book quality in the search language (“I can’t tell you that every book we have is of high quality,” says a diplomatic Aronson) and, perhaps more important, how to broaden their system’s definition of diversity.

In some ways, “this is one of the biggest public humanities projects Bates has ever taken on.”

“It made the most sense to start with racial and ethnic diversity because that’s where the idea was grounded originally,” Aronson explains, referring to her cross-group research. But now, with a robust methodology in place, they can think about bringing in other dimensions of diversity.

“We’ve talked about gender diversity, sexuality, orientation,” says Bell. “We’ve talked about socioeconomic diversity, and immigration and refugees.”

In fact, the Diverse BookFinder is as impressive for its potential as for what it has already made possible. “This is not made for an internal audience, and this is not made wholly and completely for scholarship,” Bell says. It’s about “making important work usable, accessible, findable for everybody.”

In some ways, she adds, “this is one of the biggest public humanities projects Bates has ever taken on.”

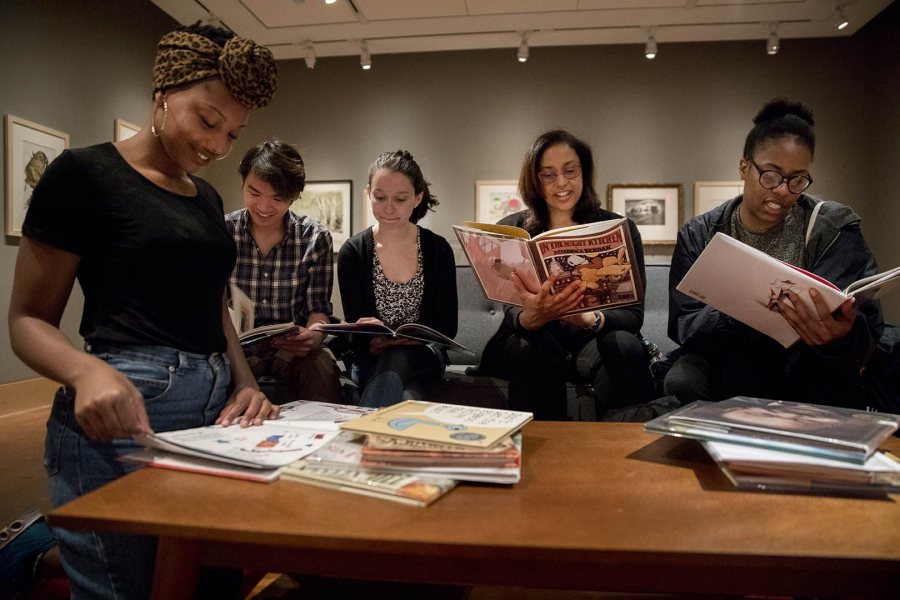

During the 2017 Short Term, Krista Aronson (second from right) and Bates students designed a new psychology course to examine issues around children’s literature. They’re pictured doing fieldwork at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Mass., last May. Aronson is teaching the new course, “Experiencing Children’s Literature,” this fall. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Aronson, who worked with students during Short Term 2017 to design a course using the Picture Book Collection as the basis for examining issues around children’s literature, says that she has “come to see picture books as socio-historical artifacts, as well as artistic artifacts. They capture our current thinking, I think, and ideas that we want to express to our children.

“Message matters,” she adds. “It’s not just numbers to me. It’s content, it’s message and representation.”

Supporters for the Diverse BookFinder include the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services and, at Bates, the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, the Faculty Development Fund, and Information and Library Services.