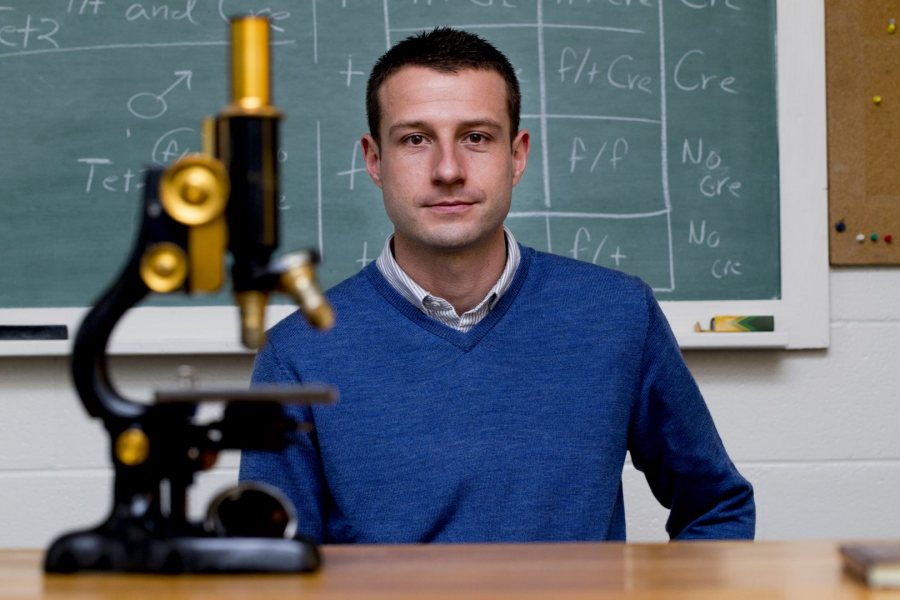

Assistant Professor of Chemistry Andrew Kennedy has a microscope in his Dana Chemistry office that he cherishes but never uses.

It’s a gold-plated Bausch and Lomb compound microscope once owned by his great-grandfather, T. Francis Kennedy, and since passed down to him.

A prominent early-20th century physician in Rhode Island, Frank Kennedy, among other good deeds, once joined a Red Cross medical response team to the great Halifax Explosion in Nova Scotia in 1917.

Frank Kennedy took the microscope with him to Paris for several research stints at the Pasteur Institute before World War II.

Back home, Frank Kennedy’s son John Kennedy — Andrew’s grandfather — used it during his own medical studies. His wife Muriel Kennedy, Andrew’s grandmother, used the microscope at the House of Good Samaritan Hospital in Watertown, N.Y., where she was a nurse.

Back home, Frank Kennedy’s son John Kennedy — Andrew’s grandfather — used it during his own medical studies. His wife Muriel Kennedy, Andrew’s grandmother, used the microscope at the House of Good Samaritan Hospital in Watertown, N.Y., where she was a nurse.

The microscope continued on to Andrew’s father, Thomas Kennedy, who took it to medical school in the 1960s. By then it was being used less and less — better equipment was coming onto the scene.

Andrew first saw the microscope as a teenager. One time his grandmother was visiting and she reminded him, “You can see anything if it exists and you have the right instrument.”

The quote is a metaphor for how Kennedy’s students are discovering what’s around them using the right instrument — in this case, Bates and the liberal arts.

Many of his students like science, he explains, and many arrived at Bates with their heart set on medical school, “but now they’ve seen new things, and are having different experiences,” he says.

“That’s what a liberal arts college does, right? It gives you a wide range of experiences and different paths to knowing things.”

The microscope is a liberal arts metaphor in another way, he adds. “This object has been useful to different people in different ways, and has been owned by a scientist, by a physician, and a nurse: three professions that have commonalities.” As a Bates graduate in the STEM field, Kennedy says, you can travel in many different directions.

In his own research on understanding the chemical mechanisms that encode and maintain long-term memory, Andrew uses far more powerful microscopes than the antique on his desk.

“But in some ways, they’re less beautiful than this instrument,” he says.