During a contract negotiating session between Argosy International and a Chinese aircraft manufacturer, a senior vice president representing the Chinese left the room for a smoke break.

A large material-supply contract was at stake. Sessions lasted up to five grueling days, each word in the bilingual contract under scrutiny.

Argosy’s CEO, Paul Marks ’83, followed the vice president. Marks told the man his head was spinning, using a saying by the Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi.

“He looked at me and said, ‘How do you know about Zhuangzi?’” Marks said. “He was really into Taoism. So we discussed Taoism for 10 minutes, walked back into the room, he turned to his team, and said, ‘Sign the contract.’”

In March 2017, Paul Marks ’83, CEO of Argosy International, speaks during the opening of the company’s manufacturing facility in Taichung City, Taiwan. (Photo courtesy Argosy International)

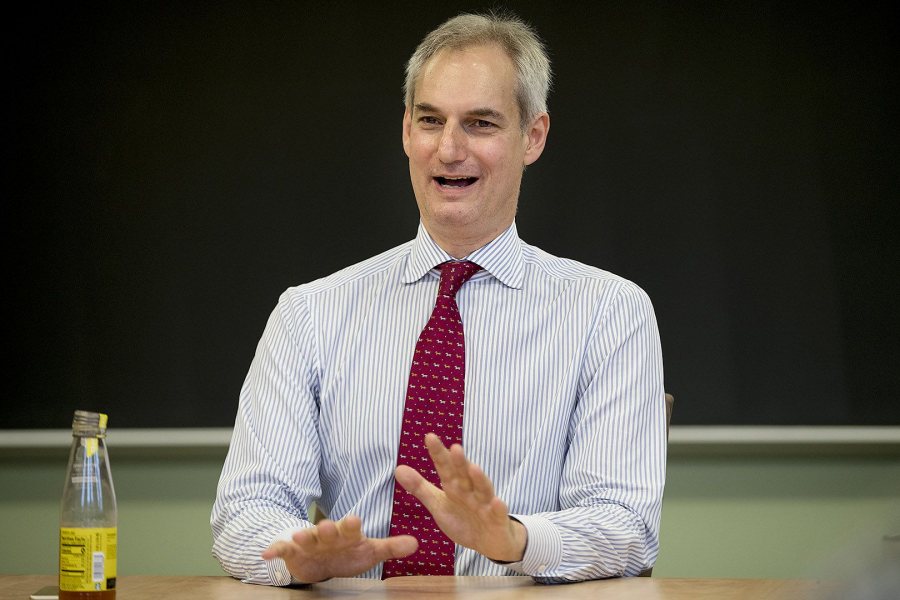

Marks, a Bates trustee who was on campus for meetings last month, told the story during his Oct. 26 talk in Roger Williams Hall, the center for language study at Bates.

Marks explained that he’d learned about Zhuangzi through a Bates history course on Chinese intellectual history, taught by now-Professor Emeritus Dennis Grafflin. By engaging with professors like Grafflin and following his interests, plus a bit of “the Bates serendipity,” Marks says he developed the ability to navigate the cultures, politics, and business climates of two interconnected but very different worlds.

All that was apparent throughout his time as a student. He went on a pioneering Short Term trip to China with a “maverick” sociology professor, George Fetter. After their tour guide bet him $5 that he couldn’t learn Mandarin, Marks became Bates’ first student of Chinese, taking daily Mandarin lessons back on campus with a Bates-hired Taiwanese language instructor, Barbara Leong.

Marks says that engaging with his Bates professors, following his interests — plus a bit of “the Bates serendipity” — have been the key to his life and career. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

After graduation, with a growing interest in all things China, Marks headed to Taiwan to study language at National Taiwan Normal University and history at National Chengchi University.

It was the mid-1980s, not long after the U.S. reestablished diplomatic relations with China, and Taiwan was still under martial law. So Marks wasn’t allowed to study the Communist Party and Cultural Revolution (instead, he was told to study the Yuan Dynasty).

Once, he was hauled in for questioning by the Taiwanese police after some classmates asked him about protests on U.S. college campuses and then held their own protest. “They showed me this propaganda film of how bad ‘Red China’ was, and they started screaming, ‘You want Taiwan to turn into this?’” Marks told his audience. “And I wasn’t scared anymore because it was so ridiculous. Then they drove me back to campus.”

Mathematics major Xuchong Shao ’20 of Shanghai and Chinese major Chelsea Anglin ’19 of Dayton, N.J., talk with Marks after his presentation. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

At the time, Taiwan was building its own fighter jet. Some of Marks’ classmates were working on the project and had been sent to the university to earn MBAs. They complained that they couldn’t acquire the aerospace materials they needed to build their plane.

“I listened to this for five months, and I said, ‘I’m going to set up a business and sell you the materials you need,’” Marks said.

Marks’ father advised him to “go work for someone and learn on their time,” so if he screwed things up he wouldn’t be left holding the bill. Instead, Marks created Argosy, which consisted of himself and one client.

Everything he needed to learn came in due time: how to run a company, the ins and outs of importing and exporting, the aerospace materials industry, and Chinese and American law and politics, the last of which Marks discussed at length with Bates students and professors during his talk.

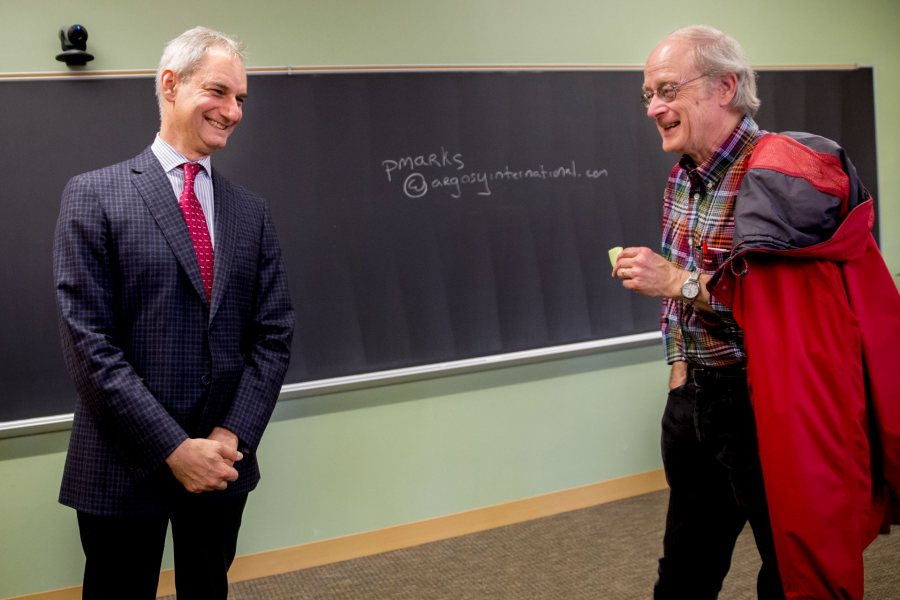

Paul Marks ’83 talks with Professor Emeritus of History Dennis Grafflin after his talk on Oct. 26. Marks considers Grafflin’s course on Chinese intellectual history to be instrumental to his work and life in China. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Argosy International grew to supply major aerospace companies with a range of composite materials and now has offices in the U.S., China, Taiwan, Malaysia, India, Singapore, Korea, France, and Australia.

When people ask Marks which Bates course had the biggest impact on his business career, his answer is always the same: Grafflin’s course in Chinese intellectual history. He’s still in touch with his former history professor, who was at his talk.

“Bates gave me the wherewithal to start a business, to believe in myself, and also the intellectual capability to analyze things and think about them logically,” Marks said.