One of the first things Emilio Valadez ’18 of San Antonio noticed about hip hop dancers in Tokyo, particularly breakdancers, is that they’re really good.

“I saw such great mastery of it during my time there,” said Valadez, himself a hip hop dancer. “I saw people that had equivalent skill levels doing this in the streets and at clubs. I was so blown away by the degree of skill and homing in on the technical aspects of this very technical, acrobatic dance form.”

Funded through a Phillips Student Fellowship, which supports experiences in a country or culture different from one’s own, Valadez spent nine weeks in Tokyo researching the art, sport, and culture of Japanese hip hop dance. He spoke about his experiences in Pettengill Hall on Dec. 4 as part of a series of student presentations ahead of a Feb. 1 deadline for several summer opportunities.

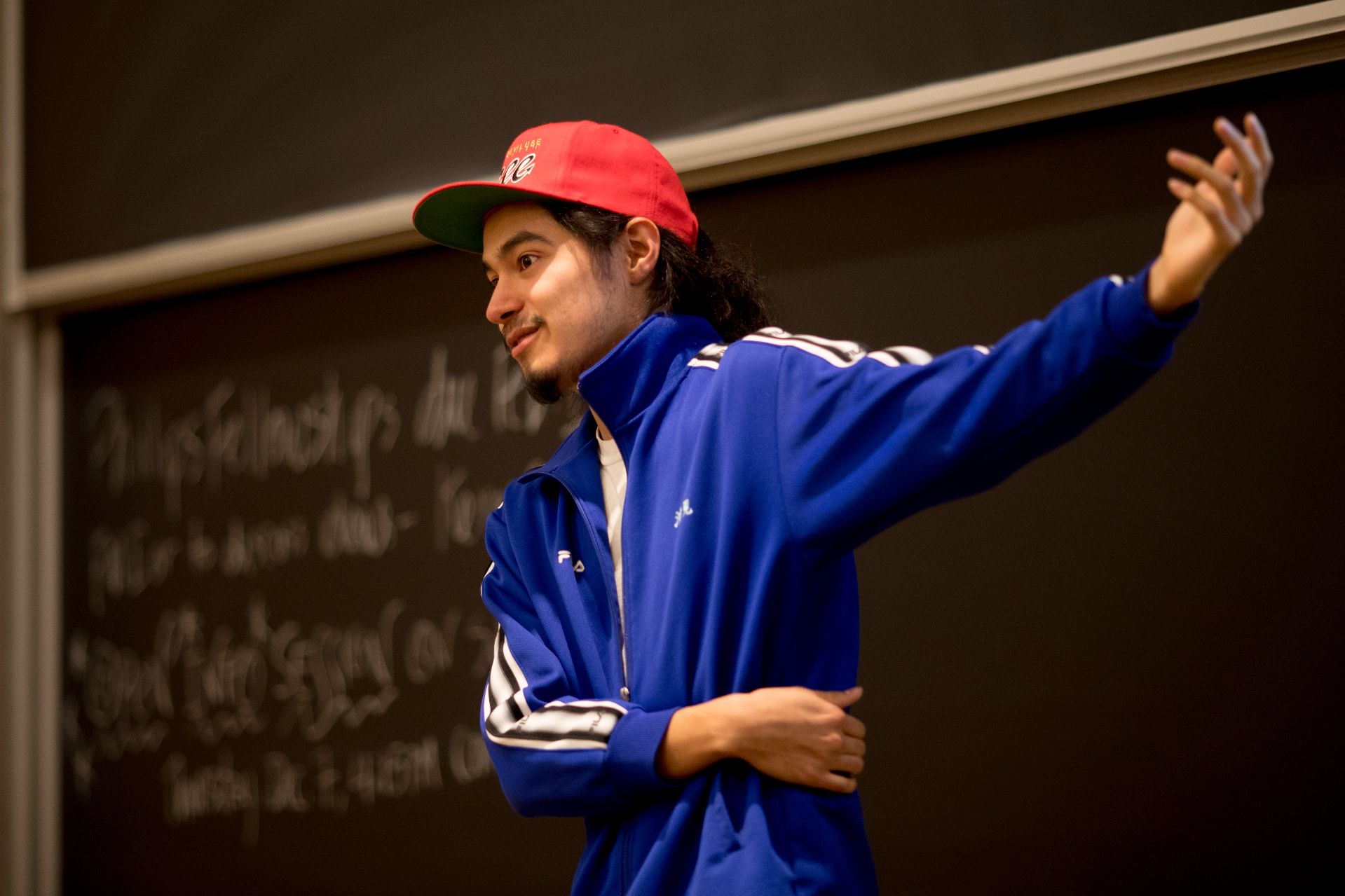

Emilio Valadez ’18 talks about his summer Phillips Fellowship in Tokyo, where he talked to breakers and lockers and poppers, learned new moves, and explored the culture and tensions of hip hop dance in Japan. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Valadez paced the front of the room as he talked about the dancers and crews he encountered in Tokyo. Pensive, he chose his words carefully and often corrected or qualified what he said. He wanted his audience to know that although his research was anthropological, he was a philosophy major, and while he had some insights into Japanese hip hop dance, he didn’t want to make any “huge claims.”

“The evidence that I got was from hanging out, talking with, and observing hip hop dancers in Japan,” he said.

Valadez, who speaks Japanese, figured out through social media where dancers in Tokyo congregated. He approached them and asked them to teach him a new move. They made him do the move over and over until he got it right. They introduced him to their friends and told him where to find more dancers.

“I met people who took this style of dance as, ‘This is my life, this is who I am, this is important to my identity.'”

Some of the dancers practiced in bars, many of which catered to a particular style, like popping, locking, breaking, or voguing; others danced in parks or on a city street, using the windows of a financial building as mirrors. In a lot of circles, mastery was a priority. So was keeping up appearances — Valadez wore a red-white-and-blue tracksuit and a baseball cap during his Bates presentation, to show that in Tokyo, you need to look the part.

“I met people who took this style of dance as, ‘This is my life, this is who I am, this is important to my identity,’” he said. “The immediate equivalent I can imagine is people pursuing this dance in New York, a really highly competitive scene. People are really focused on skill.”

Valadez also spent a lot of time with the Nova Grande crew, dancers who he said practiced in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park, or on the street, or in their own bar. Instead of practicing and perfecting any one style, they told him they saw dancing as a form of storytelling.

“They use dance to bring themselves into this interesting and imaginative space,” Valadez said. For example, “‘I want to go to the desert. How do I dance in the desert?’ And then you imagine the desert, as one of them put it. It was such a cool approach to dance.”

Hip hop dance, which is rooted in black and Latino cultures in the United States, came to Japan in the 1980s. B-boys in their 30s and 40s told Valadez that people started imitating American dancers they saw on TV, and American dancers came to Japan and imparted their craft.

Yet some of the meaning and history of hip hop was lost in translation. Valadez said many of the practitioners and fans he talked to didn’t understand the lyrics of English-language songs.

“There was a kind of disconnect that has led some to say, ‘All we were taught was the dance and the art and the sport of hip hop dance, but we were never taught the meaning and culture of hip hop,’” Valadez said. “‘We only got the aesthetics, but not quite the meaning.’ That was the narrative as I was told and as I understood it.”

While technically superb, some of the dancers that Valadez met in Japan say that the meaning and history of hip hop has been lost in translation. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The dancers Valadez met understood their work in different ways. Some thought of themselves as perfecting an American creation, “taking things from one to 10,” he said. Others considered themselves completely original.

Regardless of what exactly they were doing, they were doing it well — Valadez said part of what drew him to Japan was the precise and systematic way some dancers explained their moves in YouTube videos.

“Hip hop’s just one thing, Katsu. It’s you.”

One of the best dancers was Bboy Katsu, who started dancing as a teenager in order to look cool. He became famous and traveled, and as he learned more about hip hop, he began to feel disconnected from the genre’s origins in New York.

“He found himself in this interesting identity quandary that I think fans of hip hop dance can find themselves in, especially on the international scene — ‘What am I to this?’” Valadez said.

Katsu told Valadez that he eventually went to a mentor, who simply said, “Hip hop’s just one thing, Katsu. It’s you.”

Katsu came out of this identity crisis with an acute awareness of hip hop’s American context, but also “a universal hip hop egalitarianism, this universal view of how hip hop can save the world,” Valadez said.

Some dancers that Valadez met thought of themselves as perfecting an American creation. Others considered themselves completely original. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Valadez’s audience seemed to share some of Katsu’s awareness of the history of hip hop. They asked him about class and gender issues in Japanese hip hop, as well as Japanese society’s reaction to dancers in public.

While he described what he saw in Tokyo, Valadez stopped short of generalizing. Katsu’s understanding of hip hop was certainly not representative, he said. Some people told him they became dancers to impress people, others because it was a fun sport. Others told him, “I do this because I believe in the cause,” or, “I find this as a way to liberate myself from the almost oppressive nature of society.

“There’s this sundry of views all thrown into my noggin,” Valadez said. “I came to really appreciate the complexities of thought within the Japanese hip hop dance scene.”