On a chilly day in early November, Bates seniors Joe Tulip, Dacota Griffin, and Noah Morasch drove to Lewiston’s Kennedy Park with clipboards and GPS trackers.

Their task: to evaluate and log the coordinates of all the “natural amenities” — trees, sidewalks, benches, vacant lots with the potential for green space — that they could find.

While Griffin and Morasch pinpointed the GPS coordinates of each tree and bench, Tulip walked the perimeter of Kennedy Park, giving each sidewalk a rating — one for smooth and accessible, five for completely inaccessible to wheelchairs. The quality of sidewalks, he said, has a big impact on people’s ability to get around and get what they need.

“If walking wasn’t the easiest thing for you to do or if you were in a wheelchair, and you had to run over the sidewalk and there’s a huge bump — it makes life much more difficult,” Tulip said, as he gave the sidewalks immediately around Kennedy Park ones and twos. “It doesn’t have to be difficult.”

Noah Morasch ’18, Dacota Griffin ’18, and Joe Tulip ’18 prepare to log the natural amenities in and around Kennedy Park on Nov. 1. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

By the end of the semester, the three seniors would have a map of the natural amenities of the Tree Streets neighborhood, which Healthy Neighborhoods, a network working to improve health in Lewiston, can use to inform improvement projects.

They’d also have a grade, because the project was part of a capstone course required of every environmental studies major.

The capstone course focuses on community-engaged research and puts into practice what ES students have learned from coursework and a required internship.

“We’re playing to the applied nature of environmental studies as a field,” said Professor of Environmental Studies Holly Ewing, who taught the course with Visiting Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Francis Eanes. “We’re weaving together fieldwork, their internship, the way in which they’re thinking about activism, and the scholarly world.”

Because the major is interdisciplinary, with concentrations that emphasize natural science, social science, or humanities, students come into the capstone course with different skill sets — some have experience with, say, soil analysis, while others have worked in public health circles or with immigrant communities.

Based on their interests and competencies, Ewing and Eanes divided their 20 students into small groups, who, often in collaboration with the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, worked with seven different community organizations to address specific needs. Their projects ranged from mapping public art in downtown Lewiston to devising a way to offset carbon emissions from study-abroad-related air travel.

In December, each group submitted a final report to their professors and to their community partners, who can use the information in the real world.

“Being able to tell a story about vacant lots and safe places to play and to exercise is really important,”

Healthy Neighborhoods — many of whose members and partners live in the Tree Streets neighborhood — wants to create a “model corridor” in which improvements to indoor and outdoor amenities within a small piece of the neighborhood could inform larger projects.

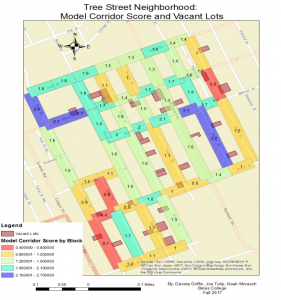

To help with that, Griffin, Morasch, and Tulip took the data they collected, including information on the trees and sidewalks of Kennedy Park, and created a series of maps showing vacant lots and other amenity locations, tree density, population density, and sidewalk quality.

The maps, which they presented to Healthy Neighborhoods coordinator Shanna Cox on Dec. 12, showed that natural amenities were not evenly distributed — for example, a tree-lined section of Horton Street had near-perfect sidewalks, while a section of Pierce Street, two blocks over, had nearly no trees and an inaccessible sidewalk.

For yet another map, the Bates students created an algorithm that factored in positive and negative attributes of each block and produced a rating.

The Bates students’ data can be combined with other data — on crime, lead poisoning, and residents’ relationships with the neighborhood, some of which is being collected by other Bates groups — to create a comprehensive map that will give Healthy Neighborhoods and Tree Street residents a picture of what is already there and what can be improved.

“Being able to tell a story about vacant lots and safe places to play and to exercise is really important,” said Healthy Neighborhoods’ Cox.

“They put another level of expertise into our project.”

Three other seniors also made a map — but theirs involves what’s in the ground, instead of what’s built on it.

Julia Nemy, Drew Perlmutter, and Dylan Thombs worked with 30 families affiliated with the Somali Bantu Community Association of Maine’s Community Farming Program. The families tend plots on a six-acre tract of land off Old Webster Road in Lewiston, growing food for subsistence and for market (other families farm sites in Auburn and New Gloucester).

Farming families in the Community Farming Program grow food for themselves and for market. The produce was featured at the Somali Bantu Community Association of Maine’s annual harvest party at Whiting Farm in September, shown here. (courtesy of Daryn Slover/Lewiston Sun-Journal)

Many Somali Bantu families farmed in Somalia and successfully do so here — but they’ve had to adjust for Maine’s soil and climate.

Nemy, Perlmutter, and Thombs’ task was to help the organization develop fertilizer and crop-rotation plans. To do so, they created a 3D map of the Lewiston farm using drone photography and overlaid the locations of crops and the boundaries of each family’s plot.

Working with the community association, Ewing’s students from her Soils class, and the University of Maine Cooperative Extension in Androscoggin County, they also sent soil off for analysis, researched fertilizer prices and the feasibility of raising chickens on unused land, and held focus groups to find out what each family needs and expects from its farm.

Thombs said his group had to balance several considerations as they developed their recommendations. Each family had to be able to cultivate its own plot independently, while still preserving the fertility of the entire field. And any efforts to increase the fertility and productivity of the field would be hindered by the fact that the farm can be accessed only via a dirt road, which can become impassably muddy; a needed gravel topping would be expensive.

Ahead of a planting demonstration in November, Dylan Thombs ’18, left, and Drew Perlmutter ’18, right, measure a 30×30 plot on the Somali Bantu Community Association of Maine’s Lewiston farm. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“We might be able to do a year where nothing grows, or we might be able to switch around some of these vegetables, or we might have to hammer harder on the fertility side of things,” Thombs said. “Even though we’re taking a lot of nutrients out, we’re putting a lot back in at the end of the year, which unfortunately would cost a little bit more money.”

Other groups of Bates students, both taking the capstone course and independently, have helped with different aspects of the Community Farming Program, such as creating a marketing plan.

“We have had a lot of good experiences with Bates College, and when we started the farming project, they put another level of expertise into our project,” said Muhidin Libah, executive director of the Somali Bantu Community Association of Maine.

Farm production manager and educator Anna Burgess shows farm manager Hassan Barjin and Bates students Julia Nemy, Drew Perlmutter, and Dylan Thombs how to use a broadfork to aerate the soil on the Somali Bantu Community Association of Maine’s Lewiston farm. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Figuring out useful solutions requires listening to and learning from community partners, which, Ewing said, is the point of the course.

“It’s not top-down,” Ewing said. “It’s not, ‘We’re going to come and solve your problem.’ Students learn as much from the partner as they might offer to the partner, and I think that’s a really important philosophy behind the class.”

The Healthy Neighborhoods students, Shanna Cox said, checked in with her every week, regularly went to the neighborhood, and accepted her guidance on defining natural amenities. They also held a focus group of Tree Street residents, who, among other things, reminded them to incorporate winter-specific issues like sidewalk plowing into their evaluations. As a possible next step, the group recommended that Healthy Neighborhoods further investigate what neighborhood residents want from a natural amenities project.

This map shows ratings of each block of the Tree Streets neighborhood, which Healthy Neighborhoods can use to identify areas of improvement. (Courtesy of Joe Tulip)

Both the Healthy Neighborhoods group and the community farming group made recommendations that their community partners can actually implement — something that’s a hallmark of the capstone course. In 2015, for example, one group evaluated the external costs associated with various ways of heating campus — information Bates then used in its decision to switch to Renewable Fuel Oil.

Cox said Healthy Neighborhoods could use the Bates students’ map of comprehensive street ratings to decide where to put a model corridor. Healthy Neighborhoods could also adopt their data collection methods once the capstone project is done.

“We’ll be able to continue to build on not just the data, but what worked and didn’t work with the mapping,” Cox said. “They’ve helped pioneer it.”

Nemy, Perlmutter, and Thombs, who worked with the Community Farming Program, presented their fertilizer and crop-rotation recommendations to some of the farming families on Dec. 8. Through an interpreter, they explained which parts of the field were more fertile than others, and which nutrients were missing. They recommended fertilizers, including lime and chicken manure, they offered a rotation plan for each family’s plot, and they suggested raising chickens on fallow land.

As the students fielded questions, it became clear that each recommendation had an associated cost or trade-off. And the dirt road would continue to pose a problem.

“It’s not top-down. It’s not, ‘We’re going to come and solve your problem.’”

Still, Libah said the Community Farming Program will try to follow the students’ advice, perhaps even creating a common plot in addition to each family’s individual plot.

“They did a great job and answered almost every question,” he said. “People were like, ‘We can actually do this?’ I think with their recommendations, we will do the lime, we will do the chicken manure, and then see what will happen from there. But to do that we have to respond to the access problem first, and that will be done next year.”

In this course, like any community-engaged course, “you can actually see the effect that you have on a community,” Thombs, who grew up in Monmouth, Maine, said. “I would not trade those experiences for any of the other courses I’ve taken. The experience of working with a community and giving back to an area that has given me a lot growing up is really important.”