Appointed to the Bates faculty this year, Matt Jadud has a rare task in higher education: building a brand-new academic program, in this case the college’s nascent Digital and Computational Studies program.

The inaugural Colony Family Professor of Digital and Computational Studies — a new faculty position funded though the Bates Campaign — Jadud will oversee the hiring of two more professors in DCS while developing the overall look and feel of the curriculum, following a roadmap developed by Bates faculty over the last couple of years.

Jadud knows what kind of people he wants for the DCS program — and what type of program Bates should have.

“I want people who are thinking hard about the human condition behind the technological condition,” he says. “And the Bates program will have a commitment to structures that are fundamentally inclusive and that value diversity.”

In training and temperament, Jadud is well-equipped for the job.

The Bates DCS program will have a “commitment to integration with the liberal arts. Most computer science departments are silos, charged with graduating computer science majors,” says Matthew Jadud, the inaugural Colony Family Professor of Digital and Computational Studies, speaking during a Back to Bates faculty discussion. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

A physics major at Kenyon College, Jadud studied education and computer science in graduate school. For his doctoral thesis at the University of Kent, in England, he explored how beginners go about writing computer programs and developed ways to determine if and how a student is struggling with learning to program.

Jadud comes to Bates after five years at Berea College, a Kentucky liberal-arts college with a profound commitment to justice, equity, and accessibility. He wants Bates students, like his Berea students, to be heavily involved in his “fundamentally human-centered” teaching and research, which focuses on how students learn computing as well as on designing and developing low-cost, open hardware for sensing and automation.

Bates Campaign gift creates Colony Family Professorship

Jadud is the inaugural Colony Family Professor of Digital and Computational Studies, a chair endowed through a $3 million gift commitment to the Bates Campaign from George and Ann Colony P’12, P’17.

Here, Jadud talks about how his own interest in computing developed, lays out his vision for the program in Digital and Computational Studies, and explains how technology can perpetuate inequality — or be a great tool for inclusiveness.

What will distinguish Bates’ DCS program?

First and foremost, the program will have that commitment to structures that are fundamentally inclusive and that value diversity. I take that very seriously.

“There should be nothing about how we design and build the program that discriminates implicitly or explicitly against any of our students,” says Matt Jadud, shown speaking with Bates parent Victoria Mills P’21 and Bates grandparent Inga-Britta Mills GP’21 during Back to Bates in September. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In a reasonable number of years, I want more than 50 percent of the students graduating from DCS to be women, because more than 50 percent of the students at Bates are women. There should be nothing structural — nothing about how we design and build the program — that discriminates implicitly or explicitly against any of our students.

Second is its commitment to integration with the liberal arts. Most computer science departments are silos, charged with graduating computer science majors. We’ll move beyond a model where every student takes one course in programming, but instead ask, what does it mean as a student of literature to have a background in computing and apply that to your field of study in a way that is true to what you’re pursuing?

What do you hope a student who majors in DCS takes away from the experience, both in terms of technical knowledge and how they think about computing in relation to the world around them?

There are three big themes. First is learning to program. Second is learning to think about problems, decompose them, integrate the needs of both technical and human concerns into the solution to that problem — that’s design thinking.

Matt Jadud: “Regardless of gender or race, you should be able to thrive and succeed in DCS at Bates without fear of discrimination or bias.”

Third is thinking about the broader human context in which the work is situated. We’ve been talking a lot this semester about issues of race and gender in computing and how it impacts the way we view ourselves, others, people we work with, the way we approach solutions.

If students only took DCS I or II and never programmed again, within five years that technical knowledge likely would have faded away. But I would hope they would remember to question themselves and those around them, when it comes to assumptions we make about people and how our biases can negatively impact how we try to solve problems in the world.

You were a physics major at Kenyon. How did you become interested in computer science? At some point did you think, ‘I’m going to do this long-term?’

Computer science snuck up on me. It was the opportunities that presented themselves along the way that shaped my direction. In college, I taught myself a little bit of programming and did independent study with a professor.

Questions involving the human condition are hard, so I like questions about how we learn and how we can support students in learning most effectively.

In grad school, at Indiana University, I enjoyed the courses in computer science. I thought I would get a master’s and go into industry. But I was funded through a teaching assistantship, and I enjoyed teaching more than I expected. Then I discovered at Indiana, there was an entire school of education — crazy, I know — and people could actually study education. I started taking courses in education and picked up most of a master’s in education along with my masters degree in computer science.

I realized I could dive deep into the intersection of education and computer science and look at how students learn programming, and I grounded my Ph.D. work in that interdisciplinary space.

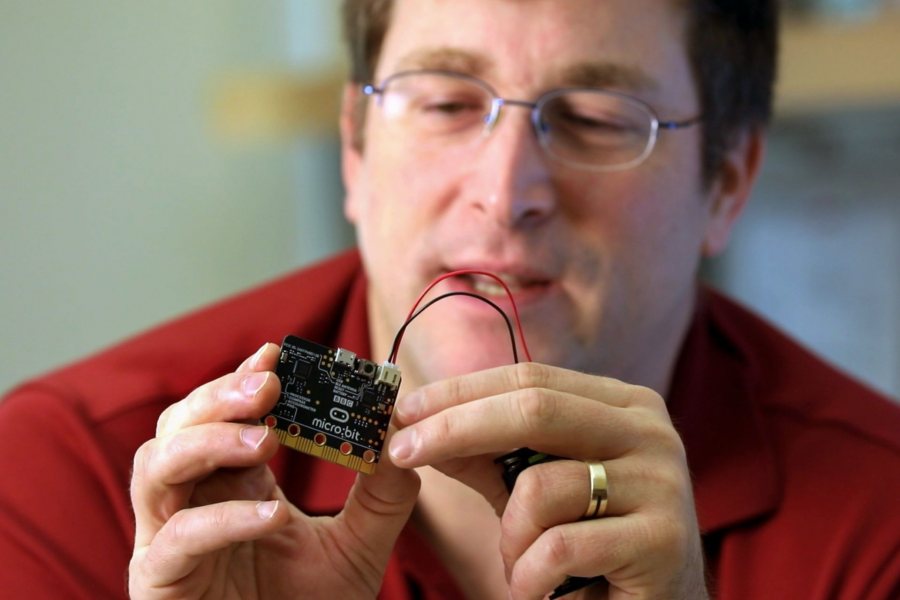

Matt Jadud shows off his “textbook,” a BBC-created gadget that teaches the young and young at heart how to code, in his Pettengill Hall office. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

What do you find most fascinating about computer science?

I think most questions involving the human condition are hard, so I like questions about how we learn and how we can support students in learning most effectively. I also enjoy some of the technical questions and the constructive aspects of the discipline.

I have learned over the years how to design and build hardware, and it provides me with an easy space to collaborate with others. It’s hard for me to walk up to most faculty and say, ‘Would you like to collaborate on a computing education research project?’ That’s a little tricky. It’s easier to say, ‘Is there a way we can integrate sensing and computing, and use that as an interface between the work that we do?’ That’s a lot more common, and it creates a lot of spaces for students to engage.

What was your experience at Berea, and how did it inform what you are doing at Bates?

Berea was really very formative. It’s a mission-driven institution. Bates and Berea’s founding stories are almost identical: Both founded in 1855 by an abolitionist minister who believed, regardless of the color of your skin, man or woman, you should have access to an education. That story of access still resonates strongly at Bates today. It’s something I was drawn to, and is part of what I’m most excited about with the DCS position.

At Berea, every student must work at the institution for a minimum of 10 hours a week. It reshapes how you think about working with students. A TA becomes an integral part of the classroom experience, because you must employ them 10 hours a week. I’m looking forward to leveraging aspects of that model here through our Purposeful Work program.

What drives you to make the tech field more inclusive?

We know that diverse teams produce better solutions. We should know that intuitively, and research bears it out time and again. Diverse teams are more creative and more productive. That said, we have implicit and explicit biases that, unfortunately, students start to experience from an early age, so we have an uphill battle at the college level. Whenever we fall into easy patterns, it’s easy to gravitate towards the people who are like us.

We want Bates graduates to be the most prepared to succeed in a global economy, in a diverse world, in a world that’s wrestling with its diversity.

I imagine community-engaged learning playing a critical role, students working with the community and applying what they’re learning as students of DCS — and then the capstone or thesis experience. That’s the skeleton of the program.

We want Bates graduates to be the most prepared to succeed in a global economy, in a diverse world, in a world that’s wrestling with its diversity, especially when we’re seeing a rise of people closing their borders and closing themselves down to people who are not like them. We need to honor and respect diversity and difference.

So why in computing? Computing touches everyone, and when graduates of DCS go on and, for example, work in the AdWords group at Google and develop algorithms that shape what people see based on keyword searches and advertising marketplaces, they become part of shaping what we see and think every day in invisible ways.

I want people who are thinking hard about the human condition behind and beyond the technological condition for all of those reasons and more.

Your website says that your research is “fundamentally human-centered.” What does that mean in the context of the DCS program and your work with students?

A lot of my work, which I’m doing with colleagues at Virginia Tech and UNC Charlotte, looks at how students learn.

It’s not uncommon for students to come in with a growth mindset — “I can learn programming” — then experience programming and go, “Oh, you have to be really smart to learn programming, and I’m not really smart.” That’s a fixed mindset, the belief that you can only succeed if you have whatever the magic is, and you believe other people have that magic, not you. How can we structure the learning and the tools we use for that learning to move students towards that growth mindset instead of that fixed mindset?

A DCS major will have a foundation for lifelong learning in computing the depth to acquit themselves well walking into a technological space.

It’s more about the people than the technology. Often, when I think about doing sensing research, we’re informing decisions that people are making. Sometimes it’s about the environment that we’re living in — the air quality in homes, for example. There aren’t many things that I do that aren’t ultimately about students or about the lived experience of people.

With that in mind, what are the most meaningful or impactful projects that you’ve done?

All of the computing education work and work around sensing and robotics have served as fertile ground for students to engage in research. In that regard, making that work accessible to students has been very impactful for those students, to provide them with a place to explore and grow. I’ve had the opportunity to publish with my students and work with them to see the entirety of the research process, from ideation through reporting and publication.

What does the ideal DCS program look like?

There are two or three courses that are essentially focused on fundamentals of programming. There’s probably a two-course sequence about learning to work in teams to solve complex problems. We need some space for depth both in terms of programming and team-based problem solving. Integrated throughout this should be conversations about diversity and inclusion and how we work with and on the human condition.

I imagine community-engaged learning playing a critical role, students working with the community and applying what they’re learning as students of DCS — and then the capstone or thesis experience. That’s the skeleton of the program.

A student majoring in DCS will have a foundation for lifelong learning in computing, and they will have the depth to acquit themselves well walking into a technological space.

What can your students expect from you as a teacher?

They can expect me to listen to them when they talk about what does and does not work for them. They can expect me to challenge them to take risks, and to have fun doing it. One of the things I have the hardest time with is getting students to move past, “Is this right?” and instead say, “Look what I did!”

We condition students over the course of 18 years that’s there’s an answer they need to come to, when what’s more important is learning to take risks and learn from the experiences they have, successful or otherwise.

I want a mindset of showing up and doing and reflecting, then we’ll layer on how to achieve excellence so we can go out into the world. If you learn to learn, that’s a powerful skill, and the only way to do it is to practice it, to experiment, and to take risks and try things. That’s what I want for these students, because computing is full of so many cool things. Go out there and do something with it.