A framed black-and-white photograph hangs in the Pettengill Hall office of Associate Professor of African American Studies Sue Houchins, a reminder of family and the power of education.

Taken 80 years ago this month, on March 15, 1938, it depicts 20 African American leaders who comprised President Franklin Roosevelt’s so-called Black Cabinet: some of the country’s finest minds and specialists in a variety of fields, including Houchins’ father, economist Joseph Roosevelt Houchins.

He’s in the second row at far right in the photo, taken by photographer Addison Scurlock, famous for documenting black Washingtonians. All 20 people in the photo are men, except the legendary educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune, known as “the First Lady of the Struggle.”

Associate Professor of African American Studies Sue Houchins. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Growing up, Sue Houchins knew of the photo because her father kept it rolled tightly in his top dresser drawer. “Every now and then we would unroll it, although it stayed rolled up for too long.”

A Cornell University–trained attorney and labor economist, Joseph Houchins led Roosevelt’s Division of Negro Affairs in the U.S. Department of Commerce until 1953. He later joined the president’s Committee on Government Contracts, where he used his skills as a lawyer and economist to address discrimination by federal contractors, including the denial of jobs to blacks at shipyards in Mississippi and Alabama.

“He was a troublemaker, and he knew what people needed,” says his proud daughter. It’s what she learned from him, she says.

In 1950, Houchins prepared an influential analysis of the African American population based on the U.S. Census, work that was featured in Ebony magazine, providing census data to a popular audience.

In 1961, he joined the economics department at Howard University, where he served as chair and mentored younger scholars. Sue Houchins occasionally meets one of those now-elderly scholars, and they sing his praises as “the father of black economics” or as the source of important economic data that strengthened the NAACP’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.

To raise awareness of her father’s contributions to American society and to academe, Sue Houchins and Howard economist Rodney Green recently co-authored a scholarly essay that chronicles his career, including publication of two Commerce reports he authored in the 1930s.

One analyzed the high failure rate of black-owned insurance companies, and the second reported on a national survey Houchins conducted to create a complete listing of black chambers of commerce that could be used for intra-racial communication and support.

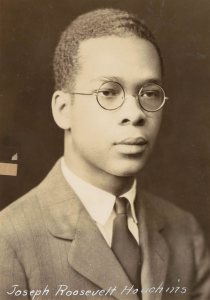

Joseph Roosevelt Houchins at Cornell University, circa 1930.

Sue Houchins also remembers the kind of father he was — one who instilled a love of learning. “On Saturdays, he would take me to a second-hand book store, put some money in my hands, and send me to where I wanted to go. He would go where he wanted to go, and then we’d have an ice cream sundae afterward.”

Born in the South in 1900, Joseph Houchins grew up in the Ithaca, N.Y., home of an uncle who was a janitor. He earned four Cornell degrees: two bachelor’s, plus a master’s and a doctorate of the science of law.

Sue Houchins says that her firebrand mother, Frankie V. Lea Houchins, a physicist and photographer, engineered her father’s Commerce job by applying for it in his name without his knowledge. They hadn’t yet wed, and he was teaching at a small historically black college in Texas at the time.

According to family lore, Frankie seemed much more interested in marrying him if she could arrange a move up North. And she succeeded.