Allen Sumrall ’16 says that professor Stephen Engel made him stop caring about what, for some, is a defining point of academe: the grade.

“I became more concerned about the material and writing a well-organized, interesting, thought-provoking paper than about the grade it would get,” says Sumrall, who took four courses with Engel and enlisted that associate professor of politics as his honors thesis adviser.

“That’s probably the single best lesson I learned in college,” Sumrall says. “He inspired my own thinking. I became truly interested in the material for its own sake.” In other words, he discovered what’s known around Bates as purposeful work: the kind of work that aligns interests, abilities, and a sense of higher meaning.

In a video by Bates director of photography Phyllis Graber Jensen, Stephen Engel explains what the Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching means to him.

“It’s only because of his courses that I’m doing a Ph.D. in government,” adds Sumrall, who’s building on his Bates honors thesis to earn that doctorate, combined with a law degree, at the University of Texas at Austin. Engel’s “willingness to nurture and promote that enthusiasm in students allowed me to discover what I wanted to do with my life.”

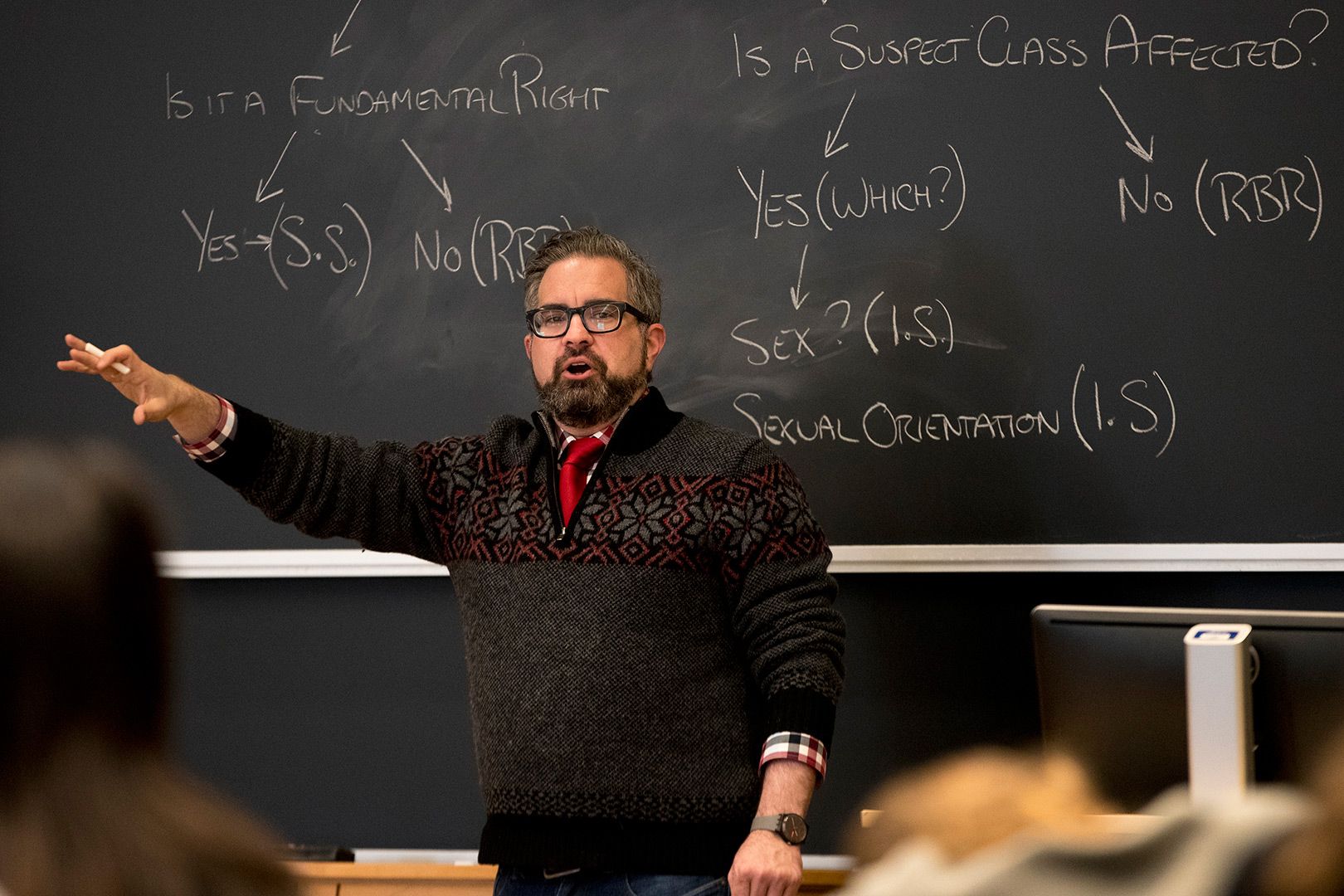

It’s not surprising that students of Engel would undergo such conversion experiences. Engel’s teaching, says politics department colleague James Richter, “is characterized by encyclopedic knowledge of his subject, clarity in its presentation, extraordinary preparation — you should see the outlines on the board when you walk into one of his 200-level classes — and an overriding concern for his students’ progress.”

Engel recently received a different kind of acknowledgement of his work with students: the 2018 edition of Bates’ pre-eminent faculty honor, the Ruth M. and Robert H. Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Charlotte Karlsen ’20 of Portland, Ore., sits with Associate Professor of Politics Stephen Engel in his Pettengill Hall office. She is taking Constitutional Law II with Engel as an independent study. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

On April 30, to mark the award, Engel presents a talk suggesting that conservatives may come to accept Supreme Court decisions that advance gay rights, because such decisions could ultimately serve the right’s legal objectives.

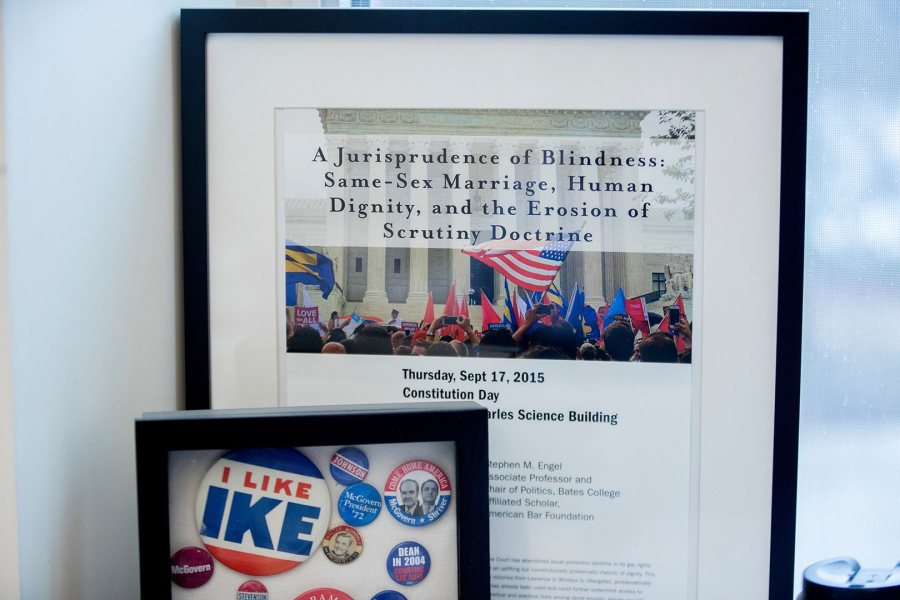

Engel joined the faculty in politics, one of Bates’ most popular majors, in 2011. The author of three books, he teaches constitutional law and development, American political development, and courses that focus on LGBT social and political mobilization.

For him, part of the appeal of a small school like Bates is that “there is both the expectation and the excitement of being in the classroom on a regular basis with undergraduates. The classroom is where I get to test ideas, challenge students, have students challenge me about those ideas,” Engel says.

In March, Timothy Lyle of Iona College and Stephen Engel (at the far end of the table) packed a Commons seminar room with their research presentation “F***ing with Dignity.” The talk was presented in coordination with Bates’ production of “Angels in America: Millennium Approaches.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“And it’s where I can really think through, in the context of politics, how contemporary policy disputes can be understood both in the moment and in the historical context.”

Now in her second semester of studying constitutional law with Engel, politics major Charlotte Karlsen ’20 of Portland, Ore., seconds Sumrall’s assessment of the professor’s ability to engage students. Where “Con Law I” could have been a dry and arcane exposition of relationships among the three federal branches and between D.C. and the states, Engel instead made it captivating.

“I think a lot of us were like, ‘We’re going to go through this kind of taxation or interstate highway conversation,’” Karlsen says, but instead, “we walked out with a really funny story or a life that had been changed by a federal decision. He really is excellent at balancing the personal and the academic in a way that makes constitutional law feel alive.”

Associate Professor of Politics Stephen Engel is the 2018 recipient of Bates’ Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She adds, “Everything he says is so specific, so direct, and so comprehensible. I think that’s critical, because he reaches every member of the class.”

“One of the things that I’ve come to learn at Bates,” says Engel, “is how I value my students so much, and how important it is to me that we create environments which are nurturing and challenging.” It’s an approach that Karlsen especially appreciated during Con Law I — which Engel taught during the emotional roller-coaster ride of the 2016 election season. He provided the tools to understand the new status quo, along with some implicit reassurance about the ultimate solidity of the U.S. political system.

“To feel like there’s a structure to our country and there’s a way that things are supposed to go,” Karlsen says, “helps us have hope for the future. And also to know what expectations we should hold for our current government. It gives students agency in discovering what responsibilities they have toward our country and how the country should be responsible to us.”

2018 Kroepsch Award recipient Stephen Engel, associate professor of politics, teaches in Pettengill Hall on April 6. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

To Allen Sumrall, who came in thinking that political science was pretty much all campaign tactics and dull institutional studies, Engel introduced intriguing dimensions of the field: specifically, the sub-discipline of American political development, which studies the causes and effects of major shifts in political history.

It was a game-changer. “APD scholars always press for historical context,” Sumrall says. “Something a political actor does at Point A may not have the same effect as if they had done it at Point B. That point alone made my brain explode.”

Engel also wins praise for his ability to challenge students while equipping them to meet the challenges. “He asks a lot of his students, but gives them all the tools to succeed,” says Bennett Saltzman ’18 of Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.

“He gives great feedback — often writing a full page of notes on every student’s paper. This feedback shaped my senior year, as the paper proposal that I wrote in ‘Politics of Judicial Power’ last semester turned into my thesis this semester.”

Politics professor Stephen Engel is known for his ability to engage students with challenging material. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The rewards are mutual, says Engel. “One of the fun things for me, especially when it comes time to advise a senior thesis, is to watch a student take responsibility and ownership over what they’re doing,” he explains. “And also the idea that they come to recognize that they are a bit of an expert — and often more of an expert — on a particular question than I am.”

On a recent weekend, Engel read “a senior thesis that was using some quantitative and statistical modeling techniques that were extraordinarily impressive.” Engel was struck by the intellectual maturity of the student’s argument: “He walked the reader through to understand not just what his methodology was, but why it was this, and why it was an improvement over existing attempts to answer the question that he was answering.”

It was a great moment, he continues. “I was like, ‘I’m learning!’” For Engel, that experience is part of a dynamic wired into the Bates education. “In the first year, you really are the professor and they really are the student.

“And by the point of the thesis, the roles can reverse in a way where the professor can be actively learning and the student can take responsibility for how to teach — that exciting moment where they realize what they actually have accomplished.

“You really do, as a professor, get to see the arc of a student’s academic progress.”