Rachel Walls ’99 was 8 years old when she first met Dahlov Ipcar, one of Maine’s best-known and most-loved artists. Ipcar, known for her children’s books as well as her work in other media, came to Walls’ classroom in Cape Elizabeth through an artist-in-residence program in Maine schools.

“She was assigned to work with us for a quarter and teach us how to write and illustrate children’s books,” says Walls, who is now an art dealer and curator, a cultural historian, and an advocate for the arts in education.

Gallery Talk

Rachel Walls ’99, proprietor of Rachel Walls Fine Art in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, offers a gallery talk on Blue Moons & Menageries at the Bates Museum of Art on June 9.

That early encounter blossomed into a friendship and professional relationship between Walls and Ipcar, who died in 2017 at age 99.

Today, Walls is the sole representative of the late Ipcar’s work — a position that led to her participation in creating the Bates College Museum of Art’s summer 2018 exhibition, Dahlov Ipcar: Blue Moons & Menageries.

Dahlov Ipcar chose Indrani Rahman, a famous classical Indian dancer and the grandmother of two Bates alums, as her model for the oil painting “Valley of Tishnar.”

Opening June 8, Blue Moons & Menageries comprises a stunning range of work by an artist known for her versatility across media. And it includes pieces seldom or never shown in public, including a painting from the 1960s for which the model was the first Miss India (for the Miss World pageant) and the grandmother of two Bates alumni.

The daughter of prominent modernist artists Marguerite and William Zorach, Ipcar reached a wide audience through the many children’s books she wrote and illustrated. She also maintained a steady studio practice, producing paintings, sculptures, and prints that are widely represented in public and private collections.

Her work is known for its bold use of color, a dramatic and romantic flair, and its many representations of animals wild and domesticated. Her works “are rich, decorative and, yes, even a little homespun. They are playful, comfortable and homey,” art critic Daniel Kany wrote in January for the Maine Sunday Telegram.

“But they are also highly sophisticated responses to some of the leading intellectual art movements of Modernism, particularly Cubism and Surrealism.” In 1939, Ipcar was the first woman — and, at age 21, the youngest artist at that time — to be featured in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

For Rachel Walls ’99, an early encounter with the artist Dahlov Ipcar blossomed into a friendship and professional relationship. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Walls’ parents collected work by Ipcar. “I did get the opportunity to visit her at her farm” in Georgetown, Maine, Walls says, “and because my parents were fans of her work, I was aware of when she was going to be in public, and I attended those events.”

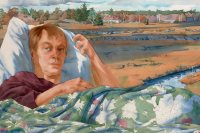

The pair reconnected in a more profound way in 2011. Walls, recovering from a serious skiing accident that affected her reading and writing, turned to Ipcar’s children’s books as she recovered those skills. She brought some Ipcar first editions to a book signing, and the artist invited her to the farm for what turned into an ongoing series of visits.

Ipcar was dealing with her own health setback, and the cruelest one for an artist: gradual loss of her vision because of macular degeneration. She enlisted Walls in an effort to organize information about the life and work of her mother, Marguerite Zorach, and especially to help re-establish Zorach’s artistic credibility, as too often her work was viewed as secondary to that of husband William and even to Ipcar’s.

“Blue Moon Square” (2007) is one of seven works in Dahlov Ipcar’s “Blue Moon” series on display at the Bates art museum.

Ipcar, says Walls, “wanted someone to really document what she felt were important aspects to the cultural significance of Marguerite Zorach in American history and art history.” (Zorach was awarded an honorary degree by Bates in 1964 — and Ipcar had her own turn in 1991.)

“When we completed that project,” Walls continues, ”we started doing the same thing with Dahlov, to make sure that her legacy was also preserved.”

“Something that was very much a part of my training at Bates is that, outside math and science, there’s no one answer to anything,” says Walls, a double major in women’s studies and in American cultural studies.

“It’s all about perspective. I learned how important it is to listen to other perspectives and contextualize how things may have been for somebody else, and how their own experiences left an imprint on how they view and experience life every day.”

Blue Moons & Menageries is full of great stories and surprising connections. The painting “Valley of Tishnar,” for instance, has an arcane but fascinating link to Bates. Named for a place in the children’s fantasy book The Three Royal Monkeys, this 1966 painting depicts a woman wandering in a jungle with leopards, tigers, zebras, and a peacock.

If Ipcar’s fantastic side often seems to draw the most attention, the artist made a serious study of educational, artistic, and psychological theory.

Ipcar’s model for the piece was a famed Indian classical dancer named Indrani Rahman, daughter of an Indian father and American mother. Named Miss India in 1952, Rahman was also the grandmother of two Bates students: Habib Wicks ’94 and Wardreath Wicks ’99, Walls’ classmate.

Meanwhile, appearing in public for the first time ever are five panels from two murals that Ipcar created in the 1930s. A gift to relatives of Ipcar’s husband, Adolph, who died in 2003, the murals illustrated two popular folk songs, “Froggy Went a-Courtin’” and “The Walloping Window Blind.”

Spanning some five decades of Ipcar’s career, and making their public debut as a group in the Bates exhibition, the “Blue Moon” paintings of the exhibition’s title afford a tidy summary of Ipcar’s oeuvre. “If you were only to look at these seven paintings, it’s a very nice overview of the range that she had, and some of the subjects that she used throughout those decades,” Walls says. “To be able to show the majority of those paintings in one space together, is, I think, a major coup.”

Rachel Walls ’99 speaks with museum visitor Jane Abrahamson on the eve of the Ipcar exhibition opening at the Bates College Museum of Art. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“There are large gaps in the years between some of the paintings,” she adds. “And that’s because the series was truly inspired by Dahlov’s dreams” — she would make a “Blue Moon” painting only in response to a dream whose imagery, what Walls describes as “these fanciful and imaginary creatures,” seemed right.

But if Ipcar’s fantastic side often seems to draw the most attention, the artist, Walls points out, made a serious study of educational, artistic, and psychological theory pertinent to youth development, with the aim of learning “to write literature that was appropriate for the illustrations that she was able to easily create for her books.” (With that in mind, Walls has worked with the Bates museum to develop educational programming for Blue Moons & Menageries, including a reading of Ipcar books coupled with an art-making session on June 26.)

Looking at her own writing and the inspiration she found, early and late, in those books, Walls sees herself as an example of what Ipcar aimed to achieve. “That’s something I find very rewarding,” she says. “I very much valued her friendship, and her creative genius, and the principles and ideals that she tried to put forward in her children’s books.”