“I’m smiling right now,” said Chris Streifel as he conducted Campus Construction Update on a whirlwind tour of labs and classrooms in Carnegie Science Hall. “Things are good.”

Specifically, what was good was the feel of the air in those different spaces. After a few days of fine-tuning to relieve inconsistent and sometimes uncomfortable temperature and humidity, Carnegie’s ventilation system was more or less stabilized by our visit on July 25, itself an uncomfortably muggy day.

Fine-tuning because why? Because Carnegie’s rooftop HVAC plant, which heats, cools, and moves air throughout the building, was shut down for a major overhaul on July 21 and a guest unit was subbed in.

Thayer Corp. technicians ponder next steps after siting a temporary HVAC unit next to Carnegie Science Hall on July 16. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

The substitute is hard to miss: a big metal box on a flatbed trailer between Carnegie and Chase, connected to the science hall’s ventilation ductwork by huge fabric hoses that snake down from the roof like a waterfall by Christo.

In the effort to optimize Carnegie’s air since the weekend switcheroo, Facility Services staff, including project manager Streifel, have tweaked airflow controls inside the building, and technicians from the Auburn firm Thayer Corp., mechanical contractor for the overhaul project, have adjusted the temporary unit. By mid-week, conditions were pretty much right.

Climate inside Carnegie isn’t merely a matter of personal comfort: Much of the research undertaken there by Bates faculty and students, some of it representing years of work, could be disrupted by extremes of temperature and humidity.

Cote Corp.’s 90-ton Grove crane towers over Carnegie Science Hall on July 23. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Even more conspicuous than the big white air ducts on Carnegie’s east facade were the visits from a crane on the Historic Quad side. The Grove-built crane, sent by Auburn’s Cote Corp. and staffed by an operator and three riggers, was here on July 13 and again July 20–24.

In the first visit, the Cote crew lifted HVAC components and tools to Carnegie’s roof and removed, among other things, the three dish antennae that have distinguished the roofline for years. Installed around 1990 to pull in satellite communications such as SCOLA rebroadcasts of foreign-language TV and radio, the antennae were made obsolete by the internet.

The extreme height of the dishes helped Cote determine what size crane to send over. As explained by Dan Cote, vice president of operations, the 90-ton-capacity crane had the reach to pluck off the dishes, but was light and compact enough to leave only fond memories behind — that is, no damage to Quad turf or foliage.

During the crane’s four-day visit, old HVAC components were taken down and their replacements — notably core items like air heating and cooling coils, new intake fans, a replacement motor and blades for the exhaust fan, etc. — were hoisted up. Cote will dispatch the crane to Bates one more time to remove tools and debris near the end of the overhaul.

While Bates is no stranger to cranes and rooftop work, Streifel points out that the physical extremes of this project — its height, the weight of components to be craned up, the mechanical complexity — make it a rarity for the college. “You have to think outside the box on ways to attack it,” he says.

With the Drifters crooning softly in the back of our mind, we went up on the roof on the 25th. Situated near the greenhouse, the air handler resembles a small building (albeit with a gaping hole cut one side to accommodate the overhaul). In fact, it’s often referred to as the penthouse (not to be confused with the Campus Construction Update penthouse).

- The building’s air handler, aka penthouse.

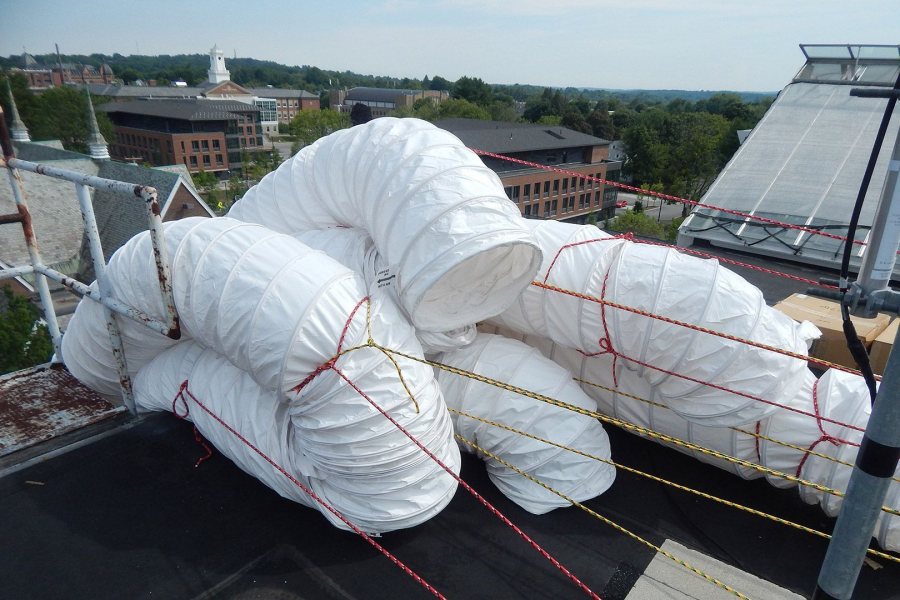

- Collapsible fabric air ducts await connection to a portable HVAC unit.

- Cooling coils will soon be installed in the penthouse.

Carnegie Science Hall’s rooftop in July 2018: The penthouse appears at right in this image from the 16th. Collapsible air ducts ready to connect. Cooling coils await installation on the 23rd. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

What route does air take through the penthouse? Outside air, aka supply air, enters on the side facing Coram and Ladd libraries, and is regulated by dampers, like those things that flap in your furnace when the wind blows.

Then the air travels through a series of components for treatment: filters to remove dust, etc., coils that use hot or cold water to adjust the air temperature, and supply-air fans that push it down into the building’s labyrinth of ductwork. Ducts then circulate air back up to the penthouse for expulsion outside by the exhaust, or return-air, fan.

Inside the penthouse, airtight doors isolate the structure’s two working “rooms.” The first air chamber you enter is the supply room. This is where the filters and the heating and cooling coils live, as well as the supply-air fans. Six new fans have replaced the old singleton and are covered with metal louvers, forming a sort of wall.

Behind that wall is where treated supply air enters building ductwork. Right now that space is sealed off with sheet plastic while it serves the rental HVAC machine. If you press your hand on the plastic you can feel the air pressure stiffening it.

At left is the return-air fan; at right is the supply-air chamber in the Carnegie penthouse. Air-heating apparatus is located at right. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

The chamber at the rear of the penthouse is the return room. Here, along with pipes and valves installed at just the right height to gouge a careless visitor’s scalp, lurks the return air fan. Resembling a jet engine from the front, this machine is formidable and deeply embedded in the air handler’s structure. As its housing is still usable, replacing the motor and blades was sufficient for the overhaul.

When we visited, the new filters and heating coil were in place and the cooling coils sat outside on the roof waiting their turn. They are squat heavy units and we didn’t envy the workers who, later in the day, would be using lift tables and a lot of elbow grease to wrestle them into place.

Replacement of the major components is certainly timely — the originals were 28 years old, and a failure of any of them, as Streifel puts it, would have been “catastrophic,” as the building has no backup HVAC. But the immediate impetus for the entire Carnegie HVAC project involved the old cooling coils.

Like a waterfall by Christo: These fabric ducts circulate air from the portable air handler on the trailer through Carnegie Science Hall. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

These condense lots of moisture out of the air, and the pan installed to capture and drain that moisture was failing. This led to water leaking into offices and labs below — including a lab we visited where, in a slightly more evolved version of stockpot-under-the-roof-leak technology, a plastic tube ran from a ceiling tile to a sink.

“The pan was replaced as much as possible at one point,” Streifel explained. “But the leaks we couldn’t address were underneath the old cooling coil. To take the coil out is a major operation, and so once you start with that — you’re not going to go in and do that level of work and not replace other aging components.”

With a dozen or two workers on the site up to 12 hours a day, every day, throughout the project, Streifel anticipates that the rooftop work itself will be complete by mid-August. Then will follow a couple of weeks of system-wide testing and tweaking, as well as moving stuff back into the fifth floor that was deranged for the overhaul.

“We’ve gotten through a lot of the hard stuff,” he said. While he’s loathe to rule out surprises that could slow things down, “I feel good about where we’re at and where we’re heading.”

Things to Come, Places to Go: A July 26 directional-drilling project on Campus Avenue provided a portent of the new science building that’s coming to Bates in 2021.

Consigli Construction, who is managing the science-building project for Bates, was working with electricians and a drilling crew to tunnel under the pavement. This was the construction equivalent of laparoscopic surgery: Enterprise Trenchless Technologies of Lisbon Falls sent a remote-control drill under and across the street, and pulled a plastic conduit through the tunnel.

Hole where the rain gets in: Workers excavate for an electrical installation near Chase Hall. A connection will be made from here to the new science building. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Meanwhile, workers from Consigli and Enterprise Electric, also of Lisbon Falls, planted an electrical vault in the vicinity of Chase Hall. The vault and conduit will ultimately route power to the science building.

As we’ve reported, the science building will be located, more or less, where Campus Construction Update is sitting and writing these words. The CCU penthouse on Nichols Street is too small to accommodate the science building, so we’ll be moving to Lane Hall, along with the rest of the Bates Communications Office staff.

A mid-July visit to Lane’s ground floor revealed an expanse of shiny metal wall studs that mapped the intriguing layout of BCO’s future home.

Bates Communications staff visit their future digs in the basement of Lane Hall on July 16. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Since 2002, BCO has been divided between two wooden houses on Nichols, with the design and digital ops teams in one and the editorial and photographic teams in the other. So the Lane Hall offices will return the communications team to a unified space — and, in fact, has been designed not just to make cross-function collaborations more likely, but to encourage them.

The emphasis on fruitful collaboration was “one of the main drivers behind the design and something we hope will set the BCO project apart,” says Shelby Burgau, who’s managing the project for Facility Services.

“We recognize the varying work styles and the need to meet with folks outside of one’s office, so a number of different spaces will be provided.”

In fact, the layout will make it all but impossible for BCO staff to avoid each other.

Priority has gone to completing three rooms — a lactation room, break area, and trash-staging room — that serve the whole building and had been taken out of service for the start of the project. Demolition and asbestos abatement began June 4, and the project reached a turning point roughly a month later as framing-in began.

As of July 26, framing was complete, utilities rough-ins were done for the three early-completion spaces, and sheetrocking of those spaces was in progress. They are expected to open to the public at the end of August. BCO will move in mid-to-late fall.

Can we talk? Send your questions and comments about past, current, and future construction at Bates to Doug Hubley. Please put “Construction Update” or “Fine-tuning because why?” in the subject line.