With the approach of a new school year, students are getting ready to move gear into all manner of housing arrangements, from singles to suites, from traditional dorms to Frye Street houses.

Seventy-two years ago, Bates debuted a housing option that remains unique for its arrangement and occupants: on-campus, apartment-style living for war veterans and their families.

As veterans returned after the war, the federal government established the Veterans Emergency Housing Program to deal with an acute shortage of housing. As part of that program, the feds helped Bates construct three apartment houses on campus.

The deal was this: If Bates did foundation work and installed utilities, the feds would “build” the apartments.

So it was that over the summer and fall of 1946, three former Navy barracks at the Auburn-Lewiston Airport were dismantled, trucked from Auburn to Bates, and reassembled at the corner of Bardwell and Russell streets, where Wentworth Adams Hall and Olin Arts Center are now. They were ready for occupancy by winter.

One of the new Bates apartments, soon to be dubbed “Sampsonville,” is reassembled on campus during the summer or fall of 1946. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

The three barracks comprised 40 apartments: 14 one-bedroom apartments, 24 two-bedroom, and two three-bedroom, with monthly rents of $38.50, $45.50, and $52.50, respectively (including utilities).

Cheap, perhaps, but veterans’ finances were tight. The GI Bill provided $500 annually for books and tuition at a time when the Bates tuition approached that figure, plus just $120 monthly in living expenses for married couples with a child.

And were there children: A May 1947 tally showed 26 young baby boomers in the three apartments, named Garcelon House, Bardwell House, and Russell House and collectively dubbed “Sampsonville,” after the benevolent Bates administrator/landlord, Charles Sampson.

“Money was tight, and movies or eating out were luxuries,” wrote Audrey and Bill Norris ’51 in “Sampsonville Revisited” in the Winter 1992 Bates Magazine.

“The men studied and the women worked,” often taking a part-time job in Lewiston. Not that the families were inclined to party or seek out traditional college fun. This was the Greatest Generation, eager to create and re-create lives and families.

A Sampsonville building is reassembled at Bates, probably in the summer of 1946. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

For veterans who enjoyed the fun and games of college life before the war, it was a 180-degree mindset change. After the war, “it was business, not monkey business,” said Ken Baldwin ’45.

“The people of Sampsonville were serious and dedicated in their pursuit of an education,” the Norrises wrote.

With their children, some of the wives of war veterans who returned to study at Bates pose outside a Sampsonville building, circa 1947. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

They recalled simple pleasures for the Sampsonvillers: “If the weather was good and the kids were sleeping well, a late-evening visit to Hector’s Pub would involve two 10-cent glasses of beer and a leisurely walk home.”

Charles Sampson was the benevolent Bates staff member who took care of the apartments and their residents.

Readers might wonder if that meant leaving the sleeping children unattended, but not to worry: Sampsonville’s wafer-thin walls meant everyone heard everything, and the residents looked out for each other.

Conversational voices passed easily from one apartment to the next, but to create the impression of privacy, it was customary to shout when intentionally communicating with a neighbor across the wall.

(Woe to those who didn’t know about the talking walls: Younger, unmarried Bates couples who babysat for Sampsonvillers could, the Norrises noted, “unwittingly provide an evening’s entertainment for the old married couple on the other side of the thin walls.”)

Charles Sampson had come to Bates in 1943 as a faculty member in the Navy’s V-12 officer-training program and stayed on after the war. A University of Maine engineering graduate and headmaster of the Huntington School for Boys in Boston before the war, he worked to integrate Sampsonville into Bates life.

Sampsonville residents play cards, including Chalder Lord ’47 (second from right) and Russell Cutter ’47 (right) and their wives (names not known). (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Sampson encouraged the families to form their own Bates club (known as the Ball and Chain Club), and the group put on an original play, Me and the Missus, in April 1947, at which Sampson received a gold key to Sampsonville. “Mr. Sampson doesn’t need a key,” noted the presenter. “For him the doors in Sampsonville are always open.”

Sampson wrote a mimeographed newsletter that could gently scold residents for not emptying refrigerator pans (they’d overflow and leak into the apartment below) while at the same time report on baby showers, new births, and day-to-day events.

Shown circa 1950, the completed Sampsonville apartments soon became a community unto itself. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Sampson’s newsletters had “unhurried wisdom and humor,” in the words of the Bates College Bulletin. “Had a piece of Polly Tooker’s pie the other day. Good!” Sampson wrote in his newsletter. Another time he added, “I continue to marvel at the way you folks help each other…. Reminds me of the good old-fashioned neighborliness that used to be traditional in this country.”

The veterans and their families came and went in a few years. There was another modest increase after the Korean conflict, but the era of the married Bates student was soon over. In fact, the college would for years later, in policy and practice, discourage the enrollment of married students or the marriage of current students.

Sampson himself retired in 1953. Later in the ’50s, Sampsonville offered housing to faculty couples and single students (men only). But with construction of Page Hall in 1957, which increased the number of student beds on campus, and Sampsonville’s growing need for maintenance, the old barracks became expendable.

By August 1957, about a month after Sampson’s death at age 74, Bates had begun to tear down and remove the buildings.

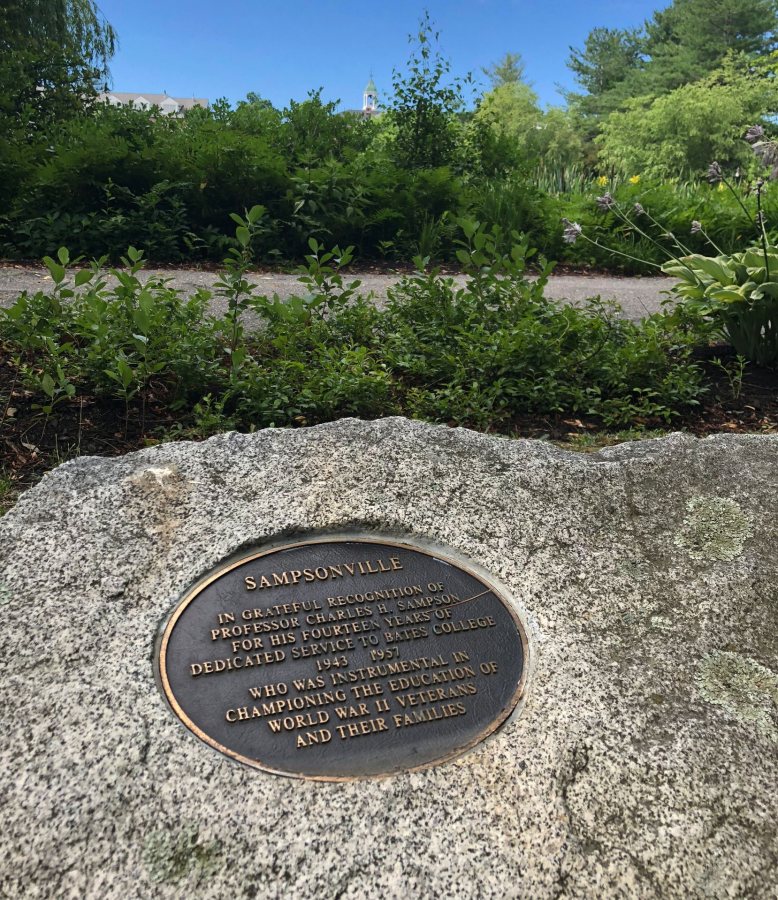

A granite memorial and plaque along Lake Andrews honor Charles Sampson for his work supporting veterans at Bates after World War II. (H. Jay Burns/Bates College)

At Reunion 1999, Sampsonville alumni gathered once again to dedicate a granite memorial in memory of their community and the man who helped them start, and in many cases re-start, their postwar lives.

Material for this story came from “Sampsonville Revisited,” by Audrey and Bill Norris ’51, Winter 1992 Bates Magazine, and “End of an Era,” by Arthur Griffiths ’50, in the September 1957 Bates College Bulletin.