In the system that geologists use to describe the history of our planet, one chronological unit is the epoch. Until this century, scientists agreed that we were living in the Holocene epoch, which began nearly 12,000 years ago as a long glacial period wound down.

But in 2000, atmospheric chemist and Nobel Prize–winner Paul Crutzen put forth the notion that, in fact, we have entered — or, actually, created — a new epoch: the Anthropocene.

With a name derived from a Greek word for “human,” it’s an epoch in which human activity, from fossil fuel use to mass human migration to natural habitat destruction, is altering nature on a planetary scale. The notion of the Anthropocene has only gained momentum since 2000, thanks to its power to capture so succinctly the scale of environmental transformation at human hands.

A still from the 2014 video The Great Silence by Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla (in collaboration with Ted Chiang), on display in the Bates exhibition Anthropocenic, opening Oct. 27

Now the Bates College Museum of Art is weighing in: Opening with a reception on Oct. 27, the exhibition Anthropocenic: Art About the Natural World in the Human Era will examine humanity’s mark on the planet with pathos, wit, and an eye-opening diversity of conceptual approaches and media.

The 17 artists and art collaboratives participating in Anthropocenic “make art about nature and the natural world, but they do it from a place that recognizes the human impacts,” says Dan Mills, Bates museum director and curator of the show.

Driving the exhibition is “the notion that our impact on the natural world is so deep that it’s actually evidenced in the geologic record.” (In fact, the Anthropocene working group of the International Commission on Stratigraphy, keepers of the official geological chronology, is even now seeking definitive geologic evidence, such as radioactive material traceable to atomic-bomb testing, that would demarcate the new epoch.)

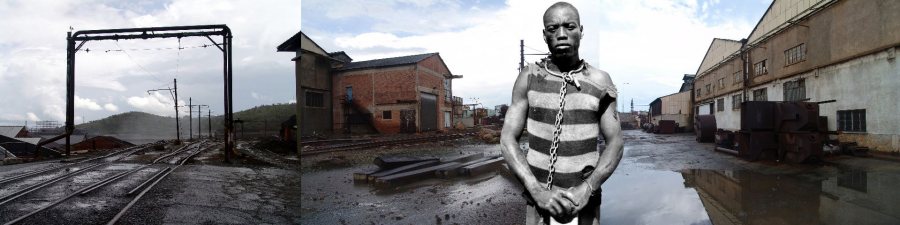

The show tackles themes, says Mills, that include environmental degradation; sea level rise and extreme weather; resource consumption and waste; war and our atomic legacy; the role of colonialism in exploiting and defiling the environment; and the ethics of stewardship of the natural world when it is privately owned.

Among the media represented in the show are such familiar practices as painting, sculpture, video, photography, and other printmaking technologies — and other media that are harder to summarize.

For instance, Adriane Herman of Cape Elizabeth, Maine, will bring to Bates her ongoing installation project Out of Sorts, which uses masses of recyclable material to confront viewers with, she writes, “the implications of excess and disposability at the personal, cultural and global levels.” Her Anthropocenic piece will do that very directly, consisting of recycling collected here on campus, baled up at the Casella Waste Systems facility, and returned here for the exhibit.

Throughout the duration of the show, Herman will engage with students through a variety of courses — notably “Lives in Place,” taught by Jane Costlow — as well as other projects.

Given the mounting presence of climate change in our daily lives and a federal government that is moving backward on environmental protection, Anthropocenic seems acutely important and timely. Art remains persuasive even as proven facts and our own perceptions fail to drive home the folly of our ways.

“There’s a broad discussion these days about our inability as a society to even have a productive discussion about climate change — people’s reluctance or resistance to that discussion,” says Costlow, the Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies and co-curator, with museum Education Curator Anthony Shostak, of the extensive programming associated with Anthropocenic.

“Simply the facts themselves are not enough. And I see this really broadly, in discussions that I follow both as a teacher and as a citizen of the world,” Costlow continues. “There’s something about understanding the scope of the issues and connecting our own lives with things that feel separate from us — artists can address those challenges in ways that are really tangible, visceral, sensory.”

The diversity of media, topics, and conceptual approaches in Anthropocenic reinforces the message. “Every artist has a different focus on the environment,” adds Emerson Krull ’19, an environmental studies major from Santa Monica, Calif., who has worked as a curatorial intern at the museum since her sophomore year.

“It’s interesting to see how each artist sees environmental change and how many different issues there are to approach — you could have a thousand artists in this show and they would all have different focuses.”

Such as: Deb Hall’s photographs, taken on a remote trail in Idaho, that probe the ethics of private ownership of nature and conflicts between private ownership and public interests. Or Laurie Hogin’s allegorical paintings whose mutant plants and animals, posed as if for classical still life or portraiture, explore complex interactions between nature and human nature. Isabella Kirkland brings painstaking technique and a classic still-life aesthetic to paintings that explore issues of species exploitation and extinction.

With coastal flooding a particular focus of her work, Maine artist Jan Piribeck uses digital geographic technology to explore artistic and scientific interpretations of the landscape, in this case Portland’s Back Cove and its increasingly flood-prone East Bayside shoreline. Piribeck co-organizes so-called King Tide Parties to spotlight peak tides along the cove — one of which will occur during winter semester and likely be the object of a public tour from Bates.

In Library of Mud, Julie Poitras Santos uses text and video to relate human memory to the sequestration of atmospheric carbon in a wetland at the Bates–Morse Mountain Conservation Area, managed by the college. She is planning walks with students to investigate these ideas.

In the artistic response to the Anthropocene that Bates has mustered up, says Costlow, “one size is not going to fit all. I love the array of voices and approaches.”