Until recently, if he wanted to study active Ebola virus, research scientist Adam Hume ’03 had to travel thousands of miles to a lab with a Biosafety Level 4 designation.

Ebola is infamously contagious and deadly, and there’s no cure. Only a dozen or so labs in the country have gained approval from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to house the virus for research.

In 2017, the lab where Hume works, the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories at Boston University, got such a designation. On his home turf — and wearing a bulky positive pressure suit — Hume can now do the work that might one day lead to an effective Ebola treatment.

In Sierra Leone in 2015, Adam Hume ’03 tests blood samples for Ebola using a “glovebox.”

Hume’s specialty is filoviruses, which include Ebola virus and the related Marburg virus. He primarily studies how Marburg infects Egyptian fruit bats, a species researchers suspect is a “reservoir” where the virus is naturally found. He also studies other aspects of Ebola virus replication.

In bats infected with Marburg, the virus replicates to lower concentrations than what is found in infected humans, meaning the viruses don’t kill or sicken the bats. Once the bats fight off the infection, they’re immune. Understanding why that is could lead to duplicating bats’ response in humans.

“Figuring out how these bats are able to limit the infection might be the key to potential therapies down the line,” Hume says.

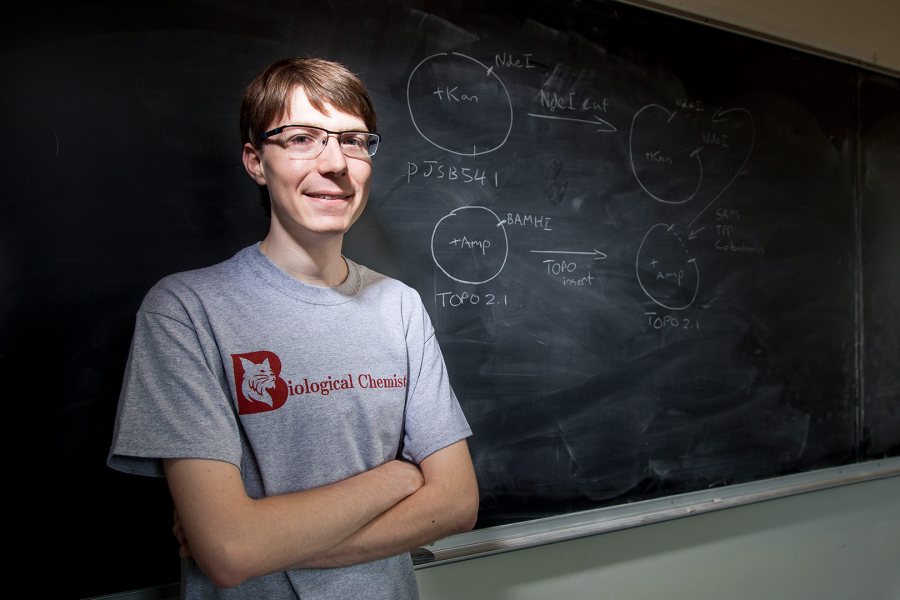

For Hume, studying filoviruses follows years of narrowing down his interests. As a biochemistry major at Bates, he initially cast a wide net, writing a senior thesis on the effects of a toxin in chickens but also taking courses in immunology and virology. Those courses bolstered Hume’s interest in infectious diseases, which he made his focus in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Adam Hume poses with Elke Mühlberger, center, and Judith Olejnik after their lab, the NEIDL, received permission to conduct research at Biosafety Level 4. (Cydney Scott/Boston University)

Jackson Emanuel ’15 also discovered an interest in infectious diseases at Bates, studying the bacteria that cause Lyme disease in particular. Following a year as a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant in Poland, he joined Rocky Mountain Laboratories, which also operates a BSL4 lab.

Emanuel participated in an effort to develop a possible vaccines for Ebola and later used elements of that vaccine to help develop a vaccine for the Zika virus.

“I like that infectious diseases combine many disciplines,” says Emanuel, now a doctoral student at the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin. “In order to study a disease well, you need to study it from many different angles.”

At Wisconsin, Hume became particularly interested in zoonotic diseases, which, like Ebola, originate in other animals but can infect humans.

Studying zoonotic diseases — and ways to prevent the jump from animals to humans — was rewarding both from a professional and an ethical point of view, Hume says.

“With habitat loss and deforestation in a lot of poorer countries, we’re seeing more of these zoonotic events,” Hume says. “It was something that was very interesting to me and something that seemed like it’s only going to become more of a problem.”

Hume focused on filoviruses at BU, working under leading filovirus researcher Elke Mühlberger. He got to work studying the way the viruses work in bats — but it would be years before the NEIDL, his base, would get the approval to study active, infectious viruses.

In the meantime, he worked in NEIDL’s Biosafety Level 2 labs, which handle less-dangerous diseases and require far less stringent safety measures. Hume analyzed filovirus “minigenomes,” small pieces of RNA which contain the end portions of filoviruses’ genetic sequences but which have had the genetic sequences that make them infectious removed. Minigenomes are safe to work with at the lower safety level, but researchers can still use them to develop antiviral medicines.

When working with active Ebola and Marburg virus was absolutely necessary, Hume would spend weeks at a time at a Biosafety Level 4 lab in San Antonio, doing experiments for his own research and for his colleagues’.

“Figuring out how these bats are able to limit the infection might be the key to potential therapies down the line.”

The training for and experience with BSL4 lab work proved useful during the Ebola outbreak that swept several West African countries from 2014 to 2016. Hume was part of a team that traveled to Sierra Leone’s Kono district in 2015 — they knew the safety measures necessarily to work with Ebola, so they could help diagnose the virus.

Hume spent six weeks analyzing blood samples and mouth swabs that came to him from around the district, using a mobile lab. “It was definitely rewarding in that it was a step closer to directly helping people,” he says.

Back at home, NEIDL continued to work for approval to operate at Biosafety Level 4. With concerns about safety within Boston’s South End neighborhood resolved, the approval finally came in 2017.

In August, samples of the virus arrived. “Dressed in spacesuit-like protective garb in her laboratory,” The Boston Globe wrote at the time, Mühlberger, Hume’s boss, “dug through several layers of packing materials and dry ice until she found a small, shatterproof plastic box, in which several tiny tubes nestled among paper towels.”

Adam Hume ’03 poses with a team that traveled to Sierra Leone in 2015 to help test blood samples for Ebola. (Courtesy of Adam Hume)

The lab is equipped with multiple redundant safety measures — the walls are 12 inches thick, the air system creates negative pressure, scientists wear protective suits connected to air hoses, and sharp objects that could puncture the suits are kept to a minimum. And the lab is staffed with people who, like Hume, are extensively trained and experienced.

Virus now on (gloved) hand, “everything takes twice as long to do,” Hume says. “You have to slow down and be more deliberate when you work in the lab. You have to think through every step of the procedure and make sure the way you’re doing it is safe.”

At the moment, Hume says, the lab is working on growing the stocks of the virus it received in August. A priority is to study Ebola in liver cells. In and out of the BSL4 lab, the lab is also investigating a newly discovered filovirus, Lloviu virus.

And Hume is — safely — on the front lines of research that could lead to a better understanding, and treatment, of a deadly virus.

“I find it very rewarding from a moral point of view and also intellectually rewarding,” Hume says. “There are a lot of new things that are undiscovered, waiting to be studied.”