“I want to share with you a series of stories that ground a set of questions that inform my work as an environmental writer,” Elizabeth Rush told a Bates audience on Oct. 27.

“I want to focus on these questions because I believe, simply put, that answers change over time and that we ought to learn the questions instead.”

Rush, an author who is exploring human adaptation to climate change, gave the annual Otis Lecture in Olin Concert Hall.

For Rush, giving the lecture was a homecoming of sorts. She taught at Bates from 2015 to 2017 as a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Humanities; while here, she wrote much her most recent book, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. Bates, she says, is a “special place where both intellectual curiosity and community are equally honored.”

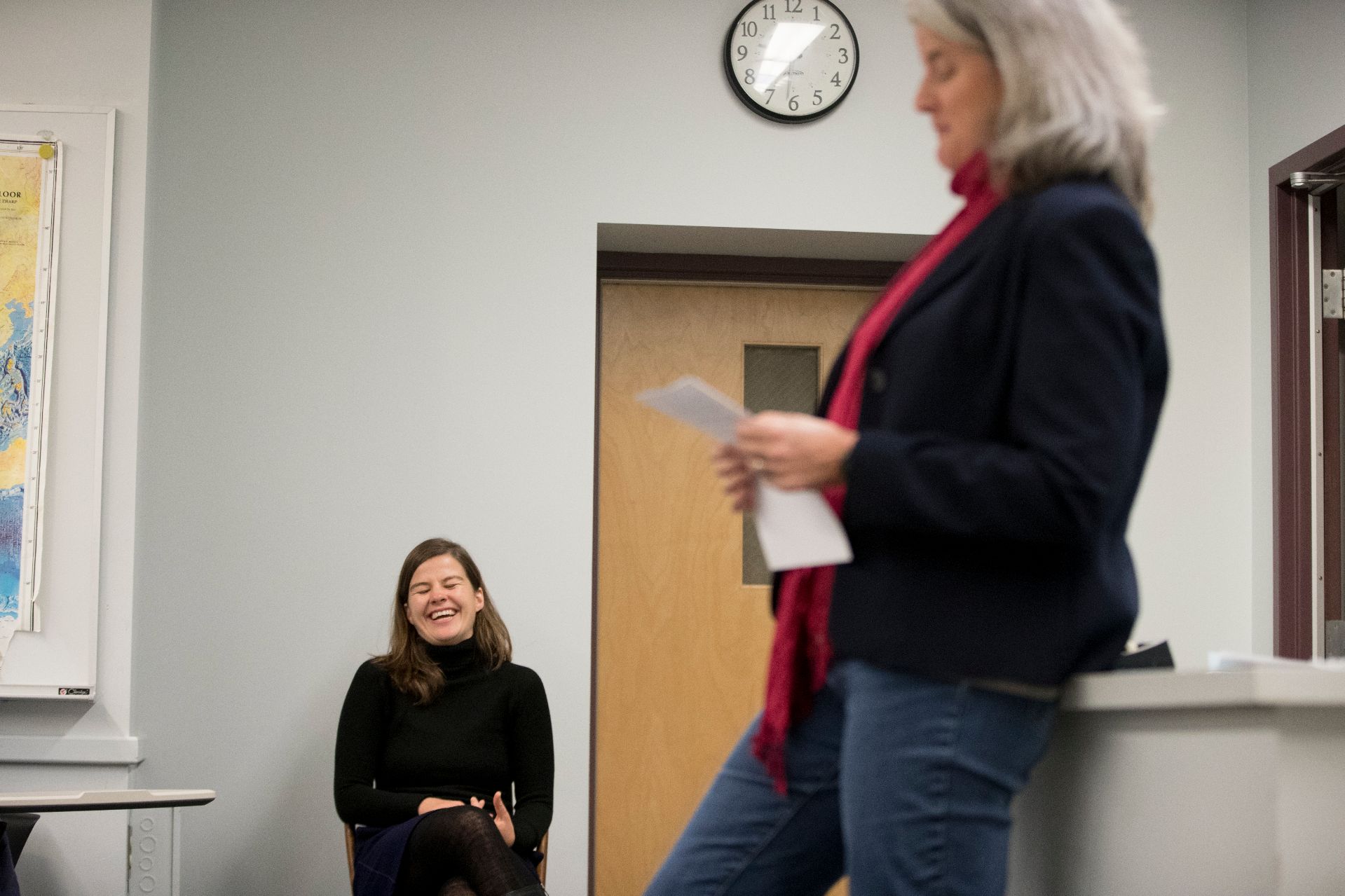

Elizabeth Rush laughs as geology professor Beverly Johnson introduces her to students in her course on global change, including the impact of greenhouse gases on global climate, sea level, and ocean acidification. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

As Rush explained to her audience, she’s beginning a big new project.

Supported by a National Science Foundation grant, she’ll head to Antarctica for the 2019 field season to research a new book about ice loss on the continent. Specifically, Rush will accompany three research teams studying the role the Thwaites Glacier will play in the upcoming years.

To access the glacier, Rush will embark on a 50-plus-day journey across the Drake Passage on the research vessel Nathaniel Palmer.

The Thwaites Glacier, she explained, has been nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier” because its melting destabilizes the entire West Antarctic ice sheet, and its potential collapse would raise sea levels worldwide.

“Thwaites is one of the most remote regions in the world,” she said. “Only 28 people in the history of the planet have ever been there.”

Upon receiving news of her grant, Rush called a male geologist. “I asked him, ‘You know what I should do to prepare?’ And he told me, ‘Pack as if you’re going to the moon.’ But I’ve never been to the moon before. I went, instead, to the library.”

In the library, Rush noticed that the “overwhelming majority of books written about Antarctica in English were written by white men, many of whom set out to conquer the continent in its various forms.

“While women have travelled to this continent before as scientists and artists and writers, as electricians as cooks, on their experience, their intimate experience of the journey had rarely made it into those Antarctic narratives.”

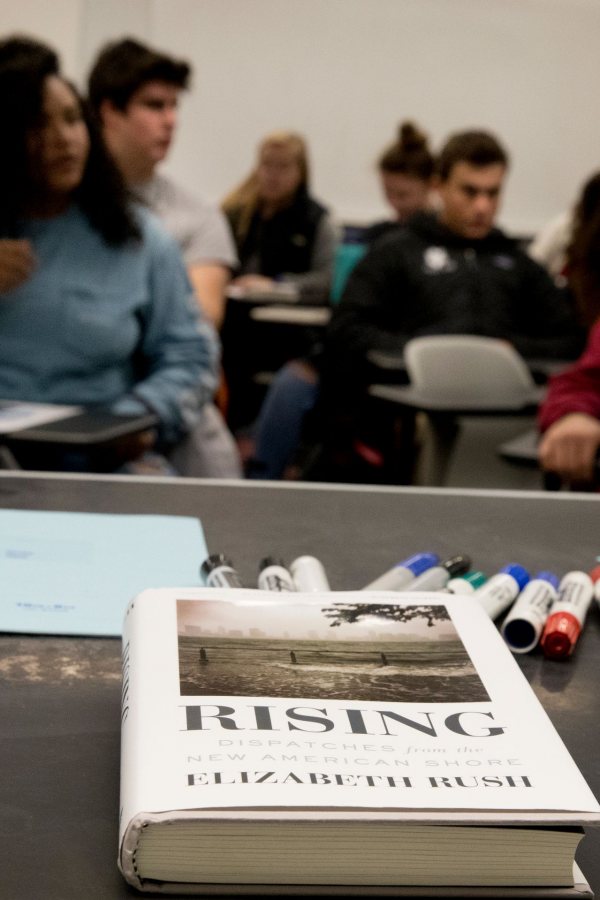

While at Bates to deliver the Otis Lecture, Elizabeth Rush speaks with students in Associate Professor of Geology Beverly Johnson’s course on global change. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

So Rush reached out to Erika Blumenfeld, “a wonderful Antarctic photographer and current artist and resident for NASA,” who told her all she needed to know about the unique experience of being a woman on the ice.

“She told me to bring baby wipes, because showers are infrequent, and more tampons than you think you will ever need,” Rush said. “Bring soda crackers, and, possibly, also bring a satellite phone in case the boat doesn’t have one.”

None of what Blumenfeld told her was in the wilderness adventure stories Rush had read in the library. Yet as a child, reading these stories helped inspire Rush to spend time outside and fostered her interest in environmental advocacy, she said.

Rush approached this dilemma by pointing to two essays. In the first, “Your Stoke Won’t Save Us,” writer and biologist Ethan Linck argues that mere enthusiasm for outdoor recreation will not fight climate change.

In the second essay, “Actually — I Think Stoke Will Save Us,” Louis Geltman, a lawyer, whitewater rafter, and the policy director for Outdoor Alliance suggests that “stoke” can also mean to help feed a fire, and that outdoor recreation fosters passion for environmental conservation and activism.

(It’s a concept Philip Otis might have greatly agreed with. Deeply committed to environmental issues, Otis, a member of the Class of 1995, died attempting to rescue an injured climber on Mount Rainier in 1995.)

Elizabeth Rush wrote much of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore while at Bates on a postdoctoral fellowship in the humanities. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“As I prepared my remarks for you all tonight,” said Rush, “I was thinking about how to make ‘stoke’ into something larger and also, in an even broader sense, how to expand the idea of who belongs in the environmental conversation in the first place.”

Rush then asked her audience to consider the groups of people who are excluded from the North American narratives of adventure and exploration.

“There are so very many that ‘us’ leaves out,” she said, “from the hundreds of millions of indigenous peoples exterminated through genocidal projects across the Americas, to those whose ancestral roots reach back to Africa and Asia and native America. Too often, that ‘us’ excludes those who didn’t have the money to launch an expedition or escape to the wilderness on the weekends.”

For Rush, questions of inclusion, exclusion, and climate change came into sharp focus in 2012, when deadly and destructive Hurricane Sandy struck while she was teaching at the College of Staten Island in New York.

As it’s believed that the storm’s fury was amplified by warming ocean waters, Rush was able to see first-hand how climate change affects people on U.S. soil today, not a century from now.

“Many of my students were missing, displaced, or worse by a seemingly unimaginable amount of water,” Rush said.

“It just rushed into the neighborhood over the informal levee system that separated the city from the seas. It entered all at once and very suddenly, and it pulled many homes off their foundations and dragged them into the surrounding tidal marsh.”

In 2015 at Bates, author Elizabeth Rush, then a Bates postdoctoral fellow, prepares to give a Language Arts Live reading. At left and right are faculty members Rob Farnsworth and Robert Strong. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Many of her students lived in low-income areas, and many were forced to leave school due to the flooding, yet this part of the story wasn’t reported by the mainstream media.

“As I watched the story unfold in the context of New York City after Sandy, I began to realize that the coverage of the storm and all it gestured toward was incomplete,” she said.

“I began to understand that sea-level rise was already disassembling some of the most vulnerable communities in one of the most powerful cities in the world.”

As these stories of climate change are becoming increasingly common, Rush encouraged her audience to question the kind of stories that they hear and tell. Who is being included in these narratives, and what voices are being left out?