You can learn a lot by looking at election seasons through the lens of gender.

The way Hillary Clinton juggled the images of commander-in-chief and mother-and-grandmother in 2016. The tenuous ease with which today’s candidates present themselves as mothers. The show of masculinity embodied by now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and the styles of masculine authority displayed by the senators who questioned him.

This fall, Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill and her students are tackling issues of gender and sexuality in politics, ranging from the historical — how did women participate in politics at the country’s founding? — to the current, and from the national to the hyperlocal.

Here, Hill talks about how sex, sexuality, and gender shape U.S. political history, the gendered politics she sees in the upcoming midterm elections, and how her class is working to elicit voters’ views of women’s concerns in Lewiston and Auburn.

What’s the central question of your course on gender and sexuality in U.S. politics?

The question is how gender shapes politics and vice versa. It’s important to think about the ways in which our ideas, our understandings of masculinity, femininity and sexuality, shape even what we think of as politics.

During a session of her course on gender and sexuality in U.S. politics, Associate Professor of Leslie Hill listens to Whitney Parrish, director of policy and program at Maine Women’s Lobby and Maine Women’s Policy Center.

The Founders thought that politics happens outside the home; that it happens only in the public space, and that space is appropriately inhabited by men, and in contrast, the home is a private space inhabited by women. The initial phase of thinking was, because women are dependent on men, they’re included in the political community as subordinates to men.

The Founders believed that women were subject to their own passions and did not have the rational characteristics required for citizenship — and that they consented to patriarchy! This is belied by Abigail Adams’ letter to her husband John as he was sitting in the Constitutional Convention. She urged him to “remember the ladies”; he wrote back that to acknowledge women as citizens would “subject us to the Despotism of the Petticoat.”

How did women, and transgender and gender-nonbinary people, participate in politics?

In domestic spaces where founders’ wives managed dinner parties for political elites. Around kitchen tables, where women wrote letters to local officials. With petitions to abolish slavery, lobby for suffrage and Progressive Era reforms. In Native communities, where women elders advised male Councils on entering treaties with the federal government. In black churches and social organizations, where working- and middle-class black women ran citizenship schools, preparing for the day when African Americans would be enfranchised.

At warfronts where some passed as male soldiers and where others fed, clothed, and tended troops as “camp followers”; and, in factories where “Rosies” riveted. Critically, in social movements, attempting to influence decisions of men holding office in formal political institutions. LGBTQ people are barely visible in these histories, but research on their more recent activism has been gaining visibility to give us a truer picture of politics.

“I want to bring to light an understanding of politics focused not just on formal institutions.”

One way of participating in politics is by entering our formal processes of decision-making on the terms of formal institutions. The vote was gained political struggle first, by working-class white men, later women, and eventually for people of color. They were not changing the institutions at all but entering political spaces from which they had been marginalized, where they had been objects of decisions rather than decision-makers.

I want to bring to light an understanding of politics focused not just on formal institutions. That’s part of the challenge with understanding women’s participation in politics. women were organizing around kitchen tables, in churches, and social clubs; LGBT folks strategized in private spaces where they met, learned, and provided care. If one were to study African American women’s political activism, you would go to the church. It’s a matter of asking, what spaces do people inhabit, where do they present themselves, their voices, their opinions, their interpretations of power?

What moments in U.S. political history are most useful in your class?

I’ll teach the 2016 election and the uses of masculinity in that campaign. In the United States, the president is the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The “role” of masculinized men is to protect families, so the defense of the political community is understood as a masculinized role. That has a great deal to do with our understanding of the presidency as masculinized.

Michael Dukakis, for example, suffered on that account in 1988. He was perceived as effeminate, not masculine enough. George W. Bush once appeared on an aircraft carrier in full uniform, when that didn’t represent his military service at all. Donald Trump used language to denigrate the masculinity of his primary opponents and delegitimize Clinton’s qualifications for the presidency.

Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill participates in a discussion during February’s Unity Conference, an annual celebration of the black community at Bates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Hillary Clinton found a way to present herself as a mother and grandmother but also as someone capable of being the commander of military forces. That actually seems to contrast with the way female candidates are presenting themselves in the 2018 elections. It’s less risky now, it seems, to talk about being a mother and easier to talk about one’s fighter pilot experience. I’m wondering how motherhood self-presentations are appearing and whether or not there are differences between conservative female candidates and liberal and progressive female candidates.

What are some other ways you’re seeing gendered politics in this election season?

In Brett Kavanaugh’s hearings, and Trump’s response. Trump suggested that men are somehow more vulnerable to false accusations of sexual assault, with the presumption that a lot of accusations are indeed false. He’s trying to challenge the widespread incidence of sexual assault and sexual violence.

There are people in important positions of leadership who are pushing back against the movement, with the mindset of, “They’re saying well, gee, now men are horrible — we can’t have that.” I see that as gender politics.

A lot of people have compared Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings to those of Clarence Thomas, who was accused of sexual harassment by Anita Hill. How do they compare for you?

You have at least one party on the Senate Judiciary committee represented entirely by white men; my students observed they were mostly older. In some ways they were embodying conventional masculine authority.

That was not unlike what went on in ’91. Senator Joe Biden, in questioning Anita Hill, at one point asked her to describe the very specific things that Clarence Thomas had done. I thought that was egregious. This time, forcing a kind of visibility of a woman’s sexuality didn’t seem to be out there in quite that same way. Maybe that was tempered by the presence of those two female Democratic senators in the hearing.

The intersection of race and gender in U.S. politics was on full display during those 1991 hearings — you yourself put your name on a famous ad in The New York Times that decried how Anita Hill was subjected to racist and sexist treatment. How are the race and gender politics different now?

There’s a fascinating documentary called Public Hearing, Private Pain, about perceptions within the African American community of what was going on in the hearings – what the racial and gender politics were. Thurgood Marshall had stepped down, and President George H.W. Bush wanted a court that appeared to include a black voice. Clarence Thomas embodied that appearance, but his politics were very much in line with those of the president who appointed him.

One of the images of 1991 was white feminists on Good Morning America saying, “Men just don’t get it.” The reaction by some black women on both sides of the Thomas-Hill hearing was, “How dare they speak without ever mentioning the racial politics of what’s going on?”

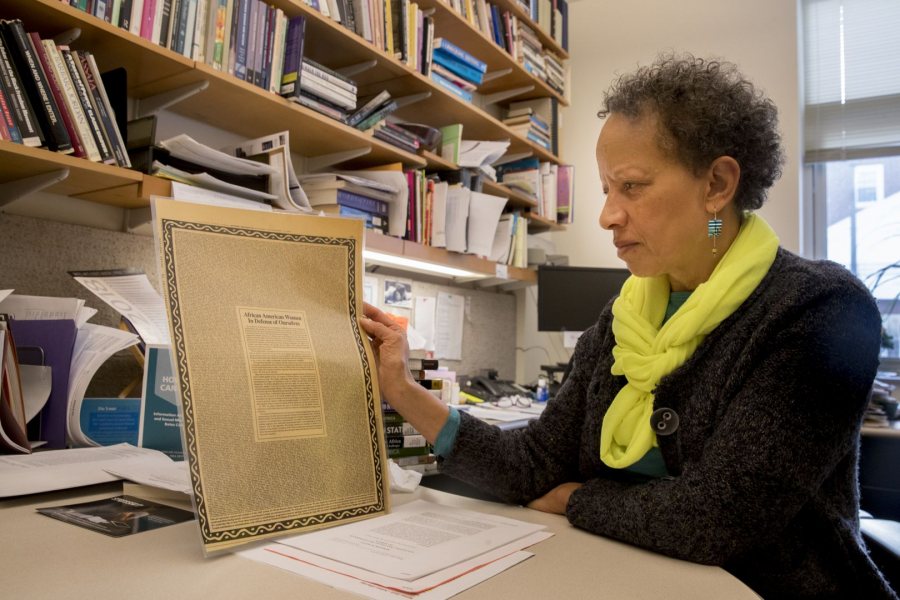

In January 2018, Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill inspects “African American Women in Defense of Ourselves,” an ad in the New York Times signed by 1,600 black women who protested the sexist and racist treatment of Anita Hill. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

With the presence of a black nominee and of a black accuser, racial politics was a subtext for the hearing itself until Clarence Thomas said, “This is a high-tech lynching.” The word “lynching” is just, trigger-trigger-trigger.

Liberals’ perception that talking about race was itself racist gave Thomas cover to intimidate opposition. “We can’t scrutinize him because it will appear racist,” so it disempowered Democrats. It put up a wall; “You can’t touch me now.” That way in which liberal discourse would not touch race made it a different kind of context.

With Kavanaugh, I still think race is a subtext, but we’re talking about the normalized sexuality of an elite, white male. If what various accusers have been saying about him bears any truth, there’s a way in which he’s using his class and race privilege as a kind of cover for his sexual predations. That raises the question, how does whiteness shape a presumption of innocence or guilt here?

One wonders if the identity of white female sexuality is so differently constructed from black female sexuality, presumed “hyper”. It seemed to come across with Anita Hill in 1991 — “Well, aren’t you just disappointed that he didn’t want to date you?” It still makes me angry, as if she’s sexually available all the time. That’s not the way Ford was approached at all.

More locally, your class is doing a project connected to voter engagement in Lewiston and Auburn. What was the project about, and what did you learn?

The Harward Center connected us to three groups. One is early childhood education students at Central Maine Community College. Two is Tree Street Youth, and these are young people, high school age. The third is the Center for Wisdom’s Women; they’re older women whose lives are multidimensional, sometimes burdened, not based in school.

My students tried to engage people in thinking about what politics is, asking, “what’s your understanding of politics and where have you learned about it?” “How does it appear in your own life?” “What are the issues that matter to you?” “What are some things that might make a difference?” Their job was to listen, listen, listen.

Whitney Parrish, director of policy and program at Maine Women’s Lobby and Maine Women’s Policy Center, helps Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill’s students debrief after the students held focus groups about voter engagement with local organizations. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Their findings were that sources of news varied. People cared about healthcare coverage and expense, child abuse, the fact that in Maine family leave is voluntary for businesses and unpaid. They’re also concerned about female representation in government.

There’s a lot of concern about Trump’s rhetoric. They fear violence, they fear being deported, and they’re concerned about what it means to build a wall. Some expressed a view that their votes don’t matter, they don’t vote because they’re disillusioned with the political scene, or because they feel they don’t know enough about the issues to vote.

What are your next steps?

With help from the Maine Women’s Policy Center, helping students understand what’s going on in the state with regard to some of those issues — whether or not there’s legislation out there, whether or not there are candidates out there that will support these issues.

The students can then go back to the community and say, “These are the people you should get in touch with; this is an issue that comes up. Make sure you vote because this is on the agenda.”

What varies across these organizations is whether or not people feel like their vote matters. We need to figure out a way to talk to people about that, because it’s just so important. The people elected in 2018 to Congress and, importantly, at the state level are going to be shaping policy agendas, the 2020 census, and a host of state-level initiatives with national significance.

That, and the fact that state legislatures have been taking up issues that Congress has not been acting on. There is a whole range of policy issues that have gone through state legislatures that are affecting people’s access to the system.

Voter ID laws, immigration policy, reproductive healthcare. We have these discussions about Democrats and Republicans at a national level, yet people develop their ideas about what politics is and how it matters to them based on what happens in their own lives, what happens locally.

![Mural on the wall of row houses in Philadelphia. The artist is Parris Stancell, sponsored by the Freedom School Mural Arts Program.Left to right; Malcolm Shabazz (Malcolm X), Ella Baker, Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass.The quote above the pictures,"We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest", is from Ella Baker, a founder of SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), a civil rights group. which amongst other contributions, helped to coordinate "Freedom Rides"in the early 1960's.Tony Fischer [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2019/01/feature-crop-Mural_Malcolm_X_-_Ella_Baker_-_Martin_Luther_King_-_Frederick_Douglass-1-200x133.jpg)