“No apology, no surrender,” Nora Chipaumire tells a Bates dance class. “However your day went today, it has now become brilliant.”

No apology, no surrender: Chipaumire returns to those words more than once in the late-afternoon session of an advanced technique course that she’s teaching as a guest artist. It’s not mere sloganizing. Instead, like the work that she makes and performs, Chipaumire’s teaching fuses the personal and political aspects of a life shaped by growing up in Zimbabwe.

Politically and economically, Chipaumire’s native country is still grappling with the legacy of colonization, as are so many others (even this one). “I’m very interested in this collusion of Europe and Africa,” she told an interviewer before the dance class.

“In my work, this collusion returns again and again, constantly trying to unpack this crucial historical moment, I think, for the entire world. What happened there has repercussions, I believe, for everyone.”

Nora Chipaumire conducts class on the Schaeffer Theatre stage. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In fact, Chipaumire’s Bates residency comes just weeks after the premiere, in October at New York City’s Kitchen, of a blockbuster piece based on her formative years in Zimbabwe.

And now it’s a Wednesday in November at Lewiston’s Bates College, and Chipaumire is facing 25 or so students in the Plavin Dance Studio. They’ll work till around six o’clock, at which point Chipaumire and a handful of students will segue into a rehearsal for a piece she is setting on the students.

Chipaumire is the fourth and final resident artist this fall to create a piece students will perform in the Marcy Plavin Fall Dance Concert (named, like the studio, for the founder of Bates’ dance program).

The goal of having resident guest artists in the dance program is to complement faculty teaching with a variety of perspectives, ideas, and teaching styles. But even amongst that variety, Chipaumire stands apart.

Based in New York City, she started making dances in 1998. Her work is grounded in personal history and the culture of the Shona, Zimbabwe’s majority indigenous people. More generally she explores stereotypes of Africa and the black performing body, art, and aesthetics.

“She has challenged all of us, students and faculty, to probe Western constructs that affect our experiences of our bodies and motion,” says Visiting Assistant Professor of Dance Julie Fox, who has hosted Chipaumire and the other resident artists in the Repertory Styles technique course.

Chipaumire began her yearlong affiliation with the college during last summer’s Bates Dance Festival, where she presented “a portrait of myself as my father” — a piece that uses boxing as a means of exploring family, masculinity, and fatherhood. (Her own father left when she was an infant.)

An intriguing aspect of Chipaumire’s practice is its emphasis on the individual, says a student in the technique course, dance and psychology major Alexandria Onuoha ’20 of Malden, Mass. Even in ensemble passages, “she doesn’t want us looking at each other. She wants us to do the journey together, but it’s okay if someone is ahead or is in a different space than the group because you’re an individual at the same time.”

Chipaumire consults with Visiting Assistant Professor of Dance Julie Fox. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

During one session, an undulation movement was frustrating some students, recalls Shae Gwydir ’20, a dance major from Port Jefferson, N.Y.

Chipaumire’s guidance typified her approach to her medium. “You have to be true to yourself and move how you ‘hear’ your body telling you to move,” says Gwydir, “not how you believe your body should move based on someone else’s directions and examples.”

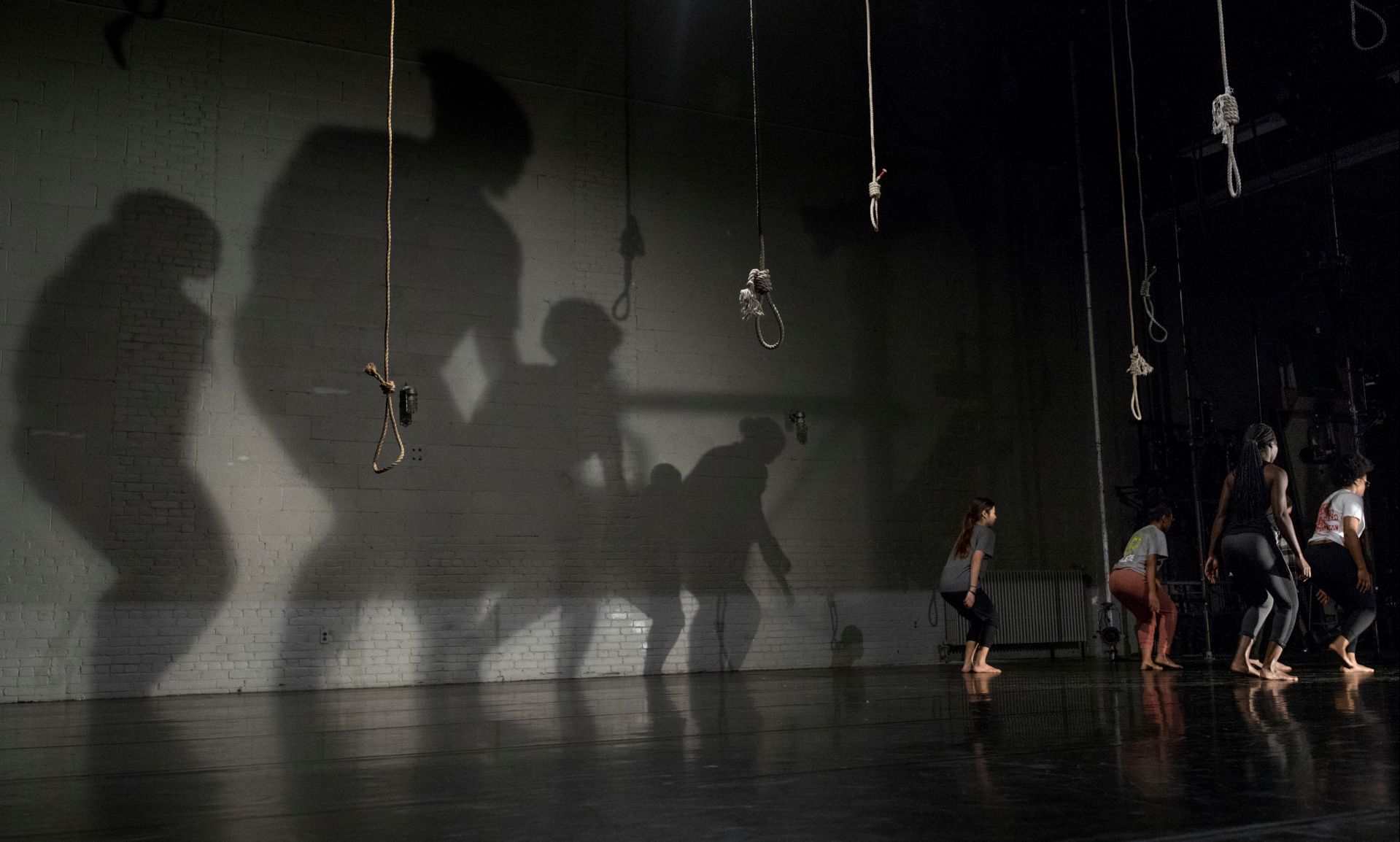

The piece Chipaumire has developed with the Bates students is based “on a figure called Nehanda, who, you could say, was a Zimbabwean Joan of Arc,” Chipaumire explained earlier in the day. Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana was a 19th-century spirit medium of the Shona people who helped inspire a popular revolt against British colonial occupation.

“Nehanda calls into the room questions about legality between settler regimes and native persons, questions about lynching, mob violence. And also other issues such as animistic belief systems in which a spirit returns again and again in different epochs.”

The piece Chipaumire has developed with the Bates students is based “on a figure called Nehanda, who, you could say, was a Zimbabwean Joan of Arc.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She says, “I try to go with the spirit of what is calling me, what is urgent for me, what do I need to understand better personally. And then that leads me into wormholes of research and discovery” — often involving intense consultation with Shona cultural leaders in Zimbabwe — “so that’s also what I am bringing to the students.”

Back in the Plavin Studio, Chipaumire is wearing a down vest over a loose, layered black outfit. From the initial warm-ups to high energy across-the-floor work that ends the session, the class has a definite arc, almost a narrative flow.

After the warmup, she and research assistant Shamar Watt lead the students through a series of moves that are cumulative in both complexity and intensity. Chipaumire watches the class closely as she leads, and issues guidance that’s sometimes sharp but not mean. In fact, her warmth is infectious. “Smiling is a good idea,” she says. “Think of your entire body as a smile.”

She always seems to be enjoying a secret joke. Sometimes she shares it. Describing a quality of corporeal suppleness and resilience, a tongue-in-cheek Chipaumire looks to the Star Trek and Star Wars glossaries. “A reed knows resistance is futile,” she says. “It is better to bend with the Force.”

Chipaumire and her research assistant Shamar Watt (right) move with dancers during class. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Given her wit, Chipaumire’s more earnest or spiritual moments, or those that touch traditions that an observer doesn’t understand, first come as a surprise. A recurring theme in the class session was the space around the students and how they should make it theirs.

“You are listening and inscribing your beingness into space,” she says. Reach up for the celestial space. Reach down for the ancestral space in the ground. “Get low, acknowledge the space that holds the ancestors.”

Chipaumire is clear that she is not representing Western dance traditions. “Don’t try the balletic gestures,” she says at one point. “Don’t give me the four o’clock tea fingers,” the extended pinky and ring finger.

At one point in the class, demonstrating into a posture of the spine and hips that she wants the students to use, she circulates among them and refers to the “swag-UH.” The swagger “is about defiance.”

Chipaumire models movements of strength and defiance in her dance. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

It’s about “what ails the black body in the world.” It’s about “the fullest presence without an apology. It allows one to walk on the street like this,” she says, striding with a fluid roll that says “I dare you” and a stare into the distance that says “See if I care.”

“We are talking,” she says at another point, “about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”