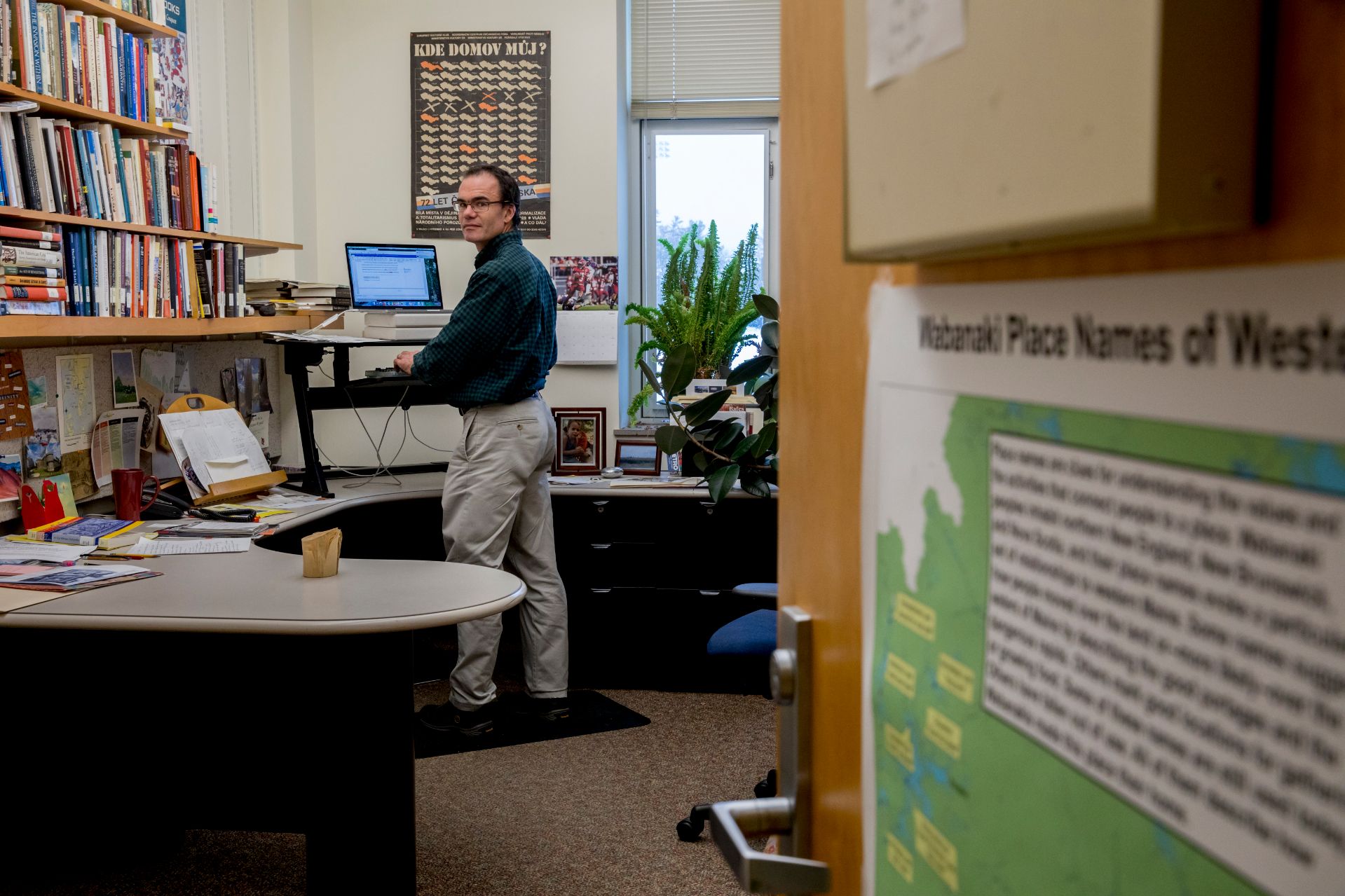

The ash tree is an important part of Wabanaki history and culture, says Associate Professor of History Joe Hall. That’s why he keeps a hunk of the hardwood — a gift from one teacher to another — in his Pettengill Hall office.

An expert on Native American interactions with Europeans in Colonial times, Hall is well-versed in the history of the five nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy that lived in Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and eastern Quebec.

In the origin story of one tribe, the Penobscot Nation, the cultural hero Gluskabe splits an ash tree with his arrow, from which emerge the first Penobscot man and woman.

Native peoples in Maine have long used the wood of brown ash (also known as black ash) trees to make beautiful and functional baskets. Hall had learned about the importance of the ash tree from a number of Wabanaki educators, but even after living in Maine for 10 years, he had never actually seen such a tree.

That changed one day about five years ago during a visit to his sons’ Auburn elementary school, where he ended up talking trees with one of their science teachers, Jim Chandler. “Can you show me what an ash tree looks like?” Hall asked.

Chandler took him into the woods behind the school and said, “This is an ash tree.” Hall also learned how to identify the species and what kind of soil it grows in.

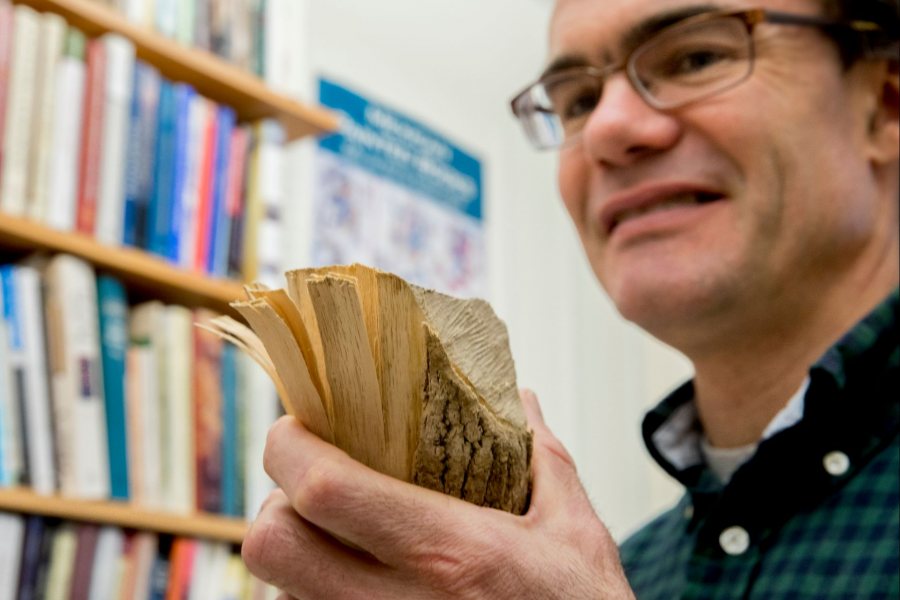

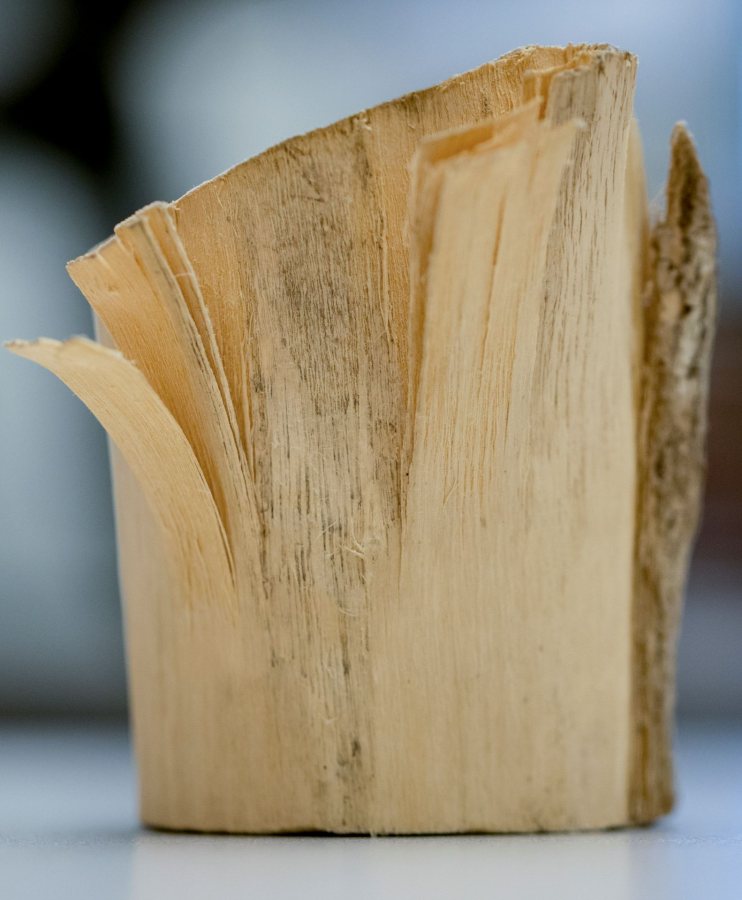

Hall then explained his interest in Wabanakis and that ash trees really matter a great deal to them. “Oh, I have something you might want,” replied Chandler, who went back into his office and returned with a piece of splintered brown ash that showed “both what the wood looks like and how it is that you actually turn this strong, hard wood into splints for weaving baskets,” Hall says.

As Hall has learned from Wabanaki basketmakers, to create the ash strips called splints, you whack the wood with the back of an axe or other blunt instrument. That separates the growth rings so eventually they peel off. A tool called a splitter may be used to make the first splints even smaller and thinner.

These strips are ideal for weaving a basket. “If you’ve ever held a wooden baseball bat,” Hall says, “you get a sense how solid and dense ash is. These strands also show how flexible it is, so the tree can be used to make baskets that are incredibly light and strong. They’re really marvelous constructions.”

This important Wabanaki tradition is now threatened by an invasive beetle species from eastern Asia, the emerald ash borer, that since 2002 has gradually spread from Michigan and other parts of the Midwest into New York and more recently Maine.

Hall shows the piece of ash to students so they can appreciate how Wabanakis turn wood into a basket, “because it doesn’t immediately make sense that you can make wood weavable,” he says. It’s also a reminder that “there’s nothing in our lives that isn’t made from other things, things that we all depend on in our connections to the world around us, such as the trees that surround us.”

Most of the time, Hall’s prized possession sits on a shelf facing his computer so he can look at it as he works. “It provides me with this connection to the people — Wabanakis and non-Indians — who have educated my children and also educated me.”