One cold Friday in November, a classroom in Pettengill Hall was a little more crowded than usual: The students in the First Year Seminar “Truth” got a visit from older Bates students who, last spring, had been instrumental in creating the brand-new course.

One by one, the new Bates students introduced themselves and told the visitors what they liked best about their First Year Seminar, whether it was a reading, film, or discussion topic — materials the older students had helped choose for them.

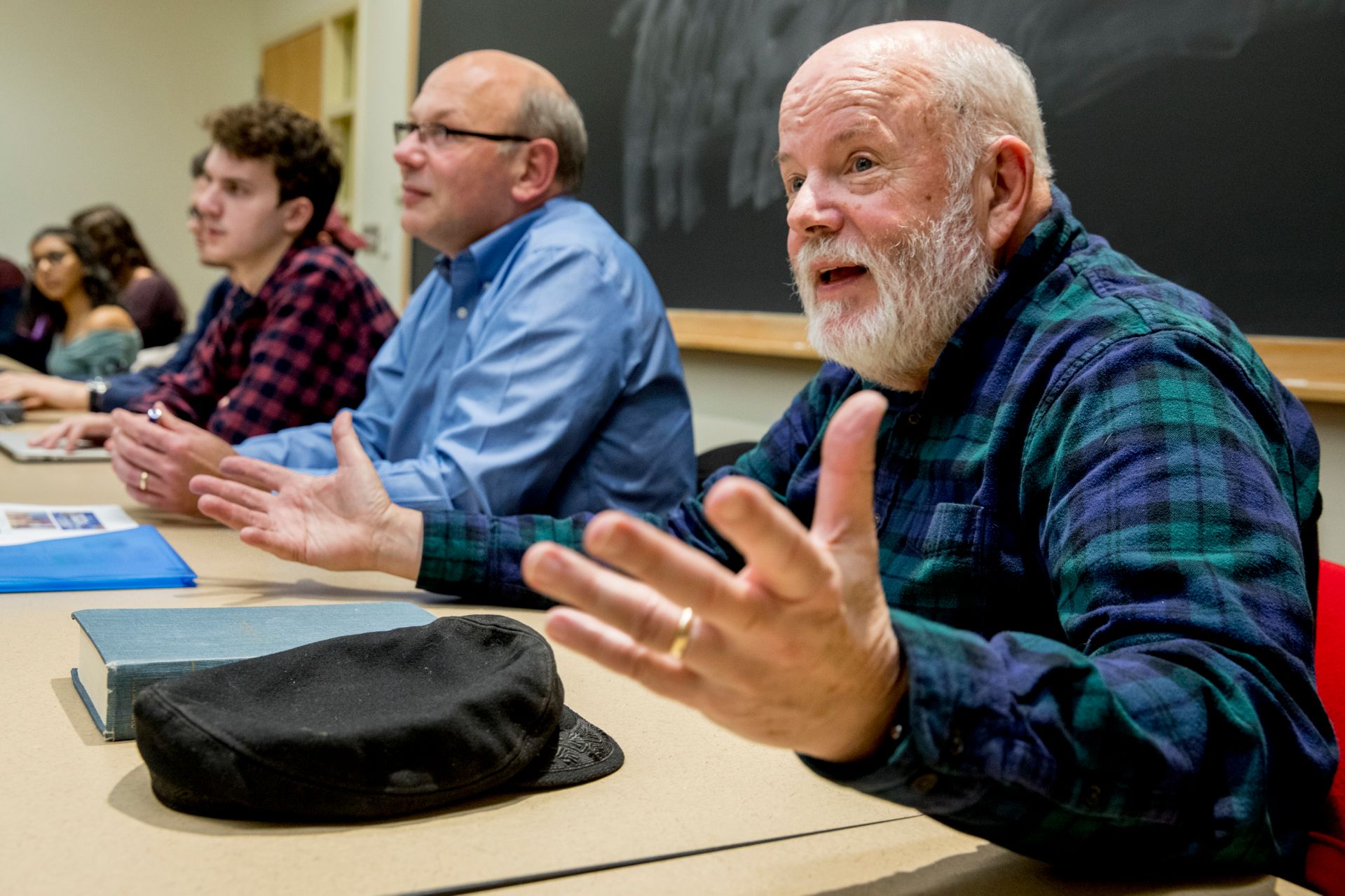

Watching the scene unfold were the two professors, Alexandre Dauge-Roth and Michael Murray, who had dreamt up the course last year, involved students in its creation, and deployed the course as one of the rare team-taught First-Year Seminars at Bates.

Professors Alex Dauge-Roth and Michael Murray touch base before class begins (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

A humanist, Dauge-Roth is a professor of French and francophone studies. A social scientist, Murray is the Charles Franklin Phillips Professor of Economics. Both are among the most popular Bates professors, each a recent winner of the Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching.

The professors listened to their students answer the “favorite material” question. One student offered Auschwitz and After, Charlotte Delbo’s memoirs of her time in a Nazi concentration camp.

Another liked comparing restorative and punitive justice. A third really enjoyed Logicomix, a graphic novel about the effort to establish logical foundations in mathematics. (Least favorite? Probably Nietzsche.)

“The main goal is not to solve the question but more to instill a higher sense of methodological awareness within students when they deal with issues of truth.”

The truth is, the new seminar is less about figuring out what “the truth” actually is and more about exploring methods of discerning and crafting truth — from philosophy to quantum mechanics to post-conflict truth and reconciliation commissions to documentary filmmaking.

Faculty and students — participants and planners — discuss the seminar. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“The value for our students is to go and explore different kinds of disciplines that all produce discourse and theories of truth,” Dauge-Roth says. “The main goal is not to solve the question but more to instill a higher sense of methodological awareness within students when they deal with issues of truth.”

The course got its start last winter as Murray mulled the idea of teaching first-year Bates students something about truth.

He recalls thinking how the current climate “is one in which notions of truth are under siege in society.” Perhaps it would be useful, right off the bat, for Bates’ newest students to be exposed to “a sophisticated sense of questions about truth.”

He felt comfortable exploring a few methodologies. As an economist, Murray clarifies reality by working with data and, he says, “looking at the relationship of trust to the economic success of societies.” He’s also studied how philosophy and the natural sciences uncover truth.

One day, after a committee meeting, Murray shared his idea with Dauge-Roth. It was chance, but fortuitous. Dauge-Roth studies memory and collective trauma through literature, film, and documentaries, particularly representations of the Rwandan Genocide.

Dauge-Roth, who incorporates philosophy and sociology into his work, approaches truth in a different way from economists or physicists. He told Murray about Delbo’s Auschwitz and After. The first book of her trilogy opens with the line, “Today I am not sure that what I wrote is true. I am certain it is truthful.”

Murray and Dauge-Roth realized their experiences with economics and natural science on the one hand, and literature, film, and sociology on the other, were in this case complementary. They decided to teach the course together.

In developing the course, the two professors cast a wide net, asking people inside and outside of the Bates community to suggest course materials. A Bates physics professor brought up an article on theoretical physics by Albert Einstein. The author of a book called Lying directed Murray to a book called Truth.

Last spring, with about twice the material they could possibly pack into a semester, Murray and Dauge-Roth invited eight juniors and seniors, several of whom are double majors across academic divisions, to spend Short Term shaping the syllabus as part of the Short Term Innovative Pedagogy and Course (re)Design program.

A group of Bates seniors who helped design the First Year Seminar ”Truth” listen as the new students taking the seminar tell them what they did and didn’t like about the course. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College) (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The students and their professors read through the material in five weeks, trying to balance the wealth of books and films with other First-Year Seminar needs, such as showing new students how to write academic papers and use the library and other campus resources. The Short Term students “helped us bring down to a manageable level the amount of reading and define an order that is intellectually stimulating,” Dauge-Roth says.

As seminar instructors, Murray and Dauge-Roth teach together, each taking on aspects of the course in which they have expertise. Then, as academic advisers, they help the students identify the aspects of the course that interest them and let their interests guide their academic paths at Bates.

“We bring in the physical sciences at a level I feel comfortable talking about, and then say to students who got excited about those ideas, ‘You should take some physics courses,’” Murray says.

In the last weeks of the course, having surveyed the philosophical, scientific, and literary underpinnings of various conceptions of truth, the class finally got to fake news. They read an article that wondered whether President Donald Trump was a liar or simply a postmodern president, and they watched a 2009 TED Talk in which Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns against defining people by a single story.

The talk, Murray says, reminded one student of a particular aspect of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, in which cave dwellers who have been shown the outside world initially wish to return to the cave, where they are more comfortable but unable to perceive other aspects of reality.

It was a gratifying moment in a course meant to teach the youngest Bates students to make connections across centuries, borders, and fields of study, something they’re encouraged to do throughout their academic careers.

“That’s very rewarding, when they are able to make those connections that were absolutely impossible or unthinkable at the beginning of the semester,” Dauge-Roth says.