In 1994, just before she entered religious life at a Carmelite monastery in Baltimore, Sue Houchins attended a party at a friend’s house. On the friend’s refrigerator was a postcard depicting a black nun, labeled, “Teresa Chikaba, Salamanca.”

Houchins took the postcard to the monastery with her and began to learn more about the African woman who had joined a convent in 18th-century Spain. Kidnapped from her homeland in West Africa, Chicaba (c. 1676–1748) was enslaved, baptized, renamed Teresa, and raised in a noblewoman’s house in Madrid.

The noblewoman freed Chicaba in her will and provided a dowry for her to join a convent, though most communities rejected her due to her skin color before she found a home among the Dominican nuns in Salamanca.

Though she performed menial tasks in the convent and was unable to take formal vows to become a nun, Chicaba became well-known in Salamanca for her holiness. After her death, a Spanish priest wrote a hagiography, a spiritual biography meant to support the cause of Catholic sainthood.

Sue Houchins later left the religious community she had joined and became an associate professor of African American studies at Bates. At her job interview, she met Baltasar Fra-Molinero, a professor of Spanish and Latin American Studies who also knew about Chicaba. The professors collaborated on Black Bride of Christ, a translation of Chicaba’s hagiography along with a scholarly introduction that explores the dynamics of race, gender, and religion in 18th-century Spain.

Here, Houchins and Fra-Molinero talk about why Chicaba’s life resonates today, and how the African nun, despite leaving behind few writings, was able to tell her own story.

Why is it important to know about Chicaba today?

Houchins: You have to understand that convents in the United States did not accept black women until the 1960s. Now there are monasteries all over Europe and the United States that bring women from the Third World and make them nuns to fill out their declining numbers. There are Africans in convents in the First World for whom Chicaba might mean something.

I’ve given papers before black theological societies. I cannot tell you how hungry they are for this book. I go and give a paper, and someone says, “I have to show you something.” They take me to a downtown Catholic church, and there is a side altar with Chicaba’s picture. She already has people devoted to her. There is a sense among black Catholics that the time is ripe for her canonization.

You both teach in interdisciplinary programs at Bates, and you argue that it’s important to study Chicaba’s life from the perspective of several intersecting disciplines, such as religious studies, Africana studies, and gender and sexuality studies. Why is that?

Houchins: There is no way, it seems to me, to read this saint’s life and not understand how race plays into it. blackness plays into her notion of herself and the notion that the Catholic Church had of her and how being a woman plays into that too.

Fra-Molinero: Until recently, there hasn’t been a serious theorizing about blackness in the literature and history of the Spanish-speaking world. It’s been more about indigenous people and mixed races. The study of blackness itself, the study of the impact of Atlantic slavery in the Spanish-speaking world — in cultural terms, in the area of religion, it’s lacking.

The story of Chicaba’s life is not enough. The hagiography itself is tremendously rich and tremendously contradictory, and we had to study those contradictions.

Chicaba was born in West Africa, which many European Catholics saw as pagan. You argue that she and Father Paniagua, the author of the hagiography, worked to “Christianize” her background. How did they do so?

Fra-Molinero: The Catholic Church knows how to reinterpret any indigenous form of religiosity: “No, that was not a female deity; that was the Virgin Mary. That was not such-and-such god; that was Saint this or Saint that.” Chicaba participated in that very consciously, because it’s a way of validating the place she came from.

Professor of Spanish Baltasar Fra-Molinero teaches a Spanish course in Roger Williams Hall. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The hagiography has a poem that is attributed to Chicaba, in which she talks about a polygamous Jesus. That’s not a typical theological position for a nun to write about her Husband, her Spouse. black theologians in the United States immediately accept that. They saw an African diasporic element — it’s clear she never forgot Africa.

Her hagiography says she was kidnapped and taken to Spain at the age of 9, but we suspect it was a bit later because she remembers too many cultural details with the accuracy that only an older person can remember.

As an enslaved woman, Chicaba grew up in Madrid in the house of a Spanish noblewoman, the Marchioness of Mancera. What was her life like there?

Houchins: The book claims that she was privileged. She learned to read and write. But the book also gives you enough of a sense that she was a slave, that she lived in the slave quarters. We think she did a certain amount of labor, but we know that she must have been treated differently enough so that other servants disliked her. I think since she was young, part of her privilege was to have been a companion to the marchioness.

Fra-Molinero: But Professor Houchins and I define the household as a literal madhouse for an enslaved person. It had to be. It was a place rife with violence. The other servants attacked her; they threw her in a pond. They wanted her to drown. A Turkish girl enslaved with her tries to murder her. There is also the danger of sexual assault; there is a priest who tries to seduce the Turkish girl.

She uses the convent as a space where she can practice her mystical union with Christ, because in no other way would she be able to endure her position.

Houchins: The governess who was set to train her either in reading or decorum hits her so hard that Chicaba says she bears the wound and the pain in the old age. This is not a soft life.

So Chicaba entered a convent after she was freed —

Houchins: We don’t know if she was freed with the stipulation that she join the convent, or whether she was freed and the only sensible choice was to join the convent. But she was freed, and she joined the convent.

Fra-Molinero: In a slave society, the freedom of those who have been slaves is always problematic. They still need the documents to prove that they are free because otherwise, by default, they are enslaved. What were the chances or the choices of a free black woman in a city like Madrid in the early 18th century? The choices were few.

How did Chicaba’s race affect her life as a nun?

Fra-Molinero: She’s not a nun.

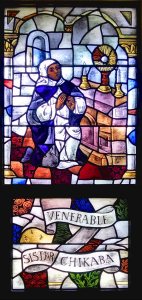

Stained glass window of Sister Teresa Chicaba by artist Silvia Nicholas, St. Dominic Chapel, Providence College (photo: Patricia Krupinski)

Houchins: Her vows — “I’m chaste, I’m going to be obedient, I’m going to be a member of the family of the Virgin Mary” — those are the prayers and the vows you say at the altar. That’s a document you sign. We don’t have that document. It doesn’t exist, because she never signed it.

Fra-Molinero: There is a moment in the hagiography when, after a church function, she invites two priests to her cell, and Jesus, as a good jealous husband, rebukes her. This anecdote told us two things. One, she considers herself the Bride of Christ, but second, and most important, it tells us her physical position in the convent.

Houchins: To receive these two priests, these two males, we know that she’s not living in the cloister with the other nuns. She never got to live inside.

Fra-Molinero: With her station, the liminal place where she slept, reminded her of where canon law stipulated she had to remain — outside of sacred enclosure. She was reminded of where she had to be. She had not made vows because of her race, because of her blackness, her Africanity.

How did the people around Chicaba notice that she was potentially saintlike?

Fra-Molinero: Chicaba clearly saw herself as a nun. She saw herself as the Bride of Christ, like all nuns. She uses the convent as a space where she can practice her mystical union with Christ, because in no other way would she be able to endure her position.

Houchins: She counseled people. She’s able to affect cures of some sort. In the monastery I entered, those sisters who had been kept out of the choir [the part of the convent that is closed off from the outside world] were the most devout in the performance of religious duties that they technically had been exempt from by virtue of their lower status.

“She succeeds in telling us, ‘My life was hell, and these were the culprits.’”

Chicaba tells you, “I know how to set up a breviary. I know how to say the Divine Office.” I think that she exhibited a kind of piety, besides the gifts she had for curing and for counseling, that made her very, very special. It must have seemed even more special because she was a black woman.

You point out that the hagiography was written to support Father Paniagua’s own agenda. You argue, however, that Chicaba’s voice comes through in the text. How so?

Fra-Molinero: One of the discussions we had was to say, “In what sense is this a typical hagiography, and in what ways does it depart from the typical hagiography, typical story and the life of a nun who’s saintly?”

Professor Houchins came up with the idea to look to the Protestant tradition of black women who tell to other people — particularly men —their spiritual narrative as well as the “as-told to-slave narratives.”

We say this hagiography is an as-told-to slave narrative. There are no other hagiographies like this in the Catholic tradition in which the story of her enslavement is so central — all the way until Chapter 19 of the 40 chapters of the book, she’s enslaved. Paniagua could have put it in just one chapter and then moved on to her life in the convent.

Black Bride of Christ, by Balthasar Fra-Molinero and Sue Houchins, is on display in the Ladd Library along with other publications by Bates faculty.

But no. There is all this suffering, all this violence. In other hagiographies, particularly of martyrs, the violence is exerted by enemies of the faith, sometimes they are the Muslims or indigenous people, or Protestants against Catholics, but here the violence is done by fellow Catholics.

These acts are in plain daylight, and [committed by] people from the system. That is where we find her voice. She succeeds in telling us, “My life was hell, and these were the culprits.”