In a classroom at the St. Mary’s Nutrition Center in Lewiston one Thursday evening in late November, every inch of space was in use.

Pine frames, built to fit into the smallest bathroom window or the largest bay window, lined each wall. About a dozen people worked at several stations in assembly-line fashion, taping the sides of the frames, wrapping the frames with polyolefin film, heat-sealing the film into place, and finishing the frame with weatherstripping.

The final product: an easy-to-install window insert that keeps homes well-insulated in the winter cold and brings down heating costs.

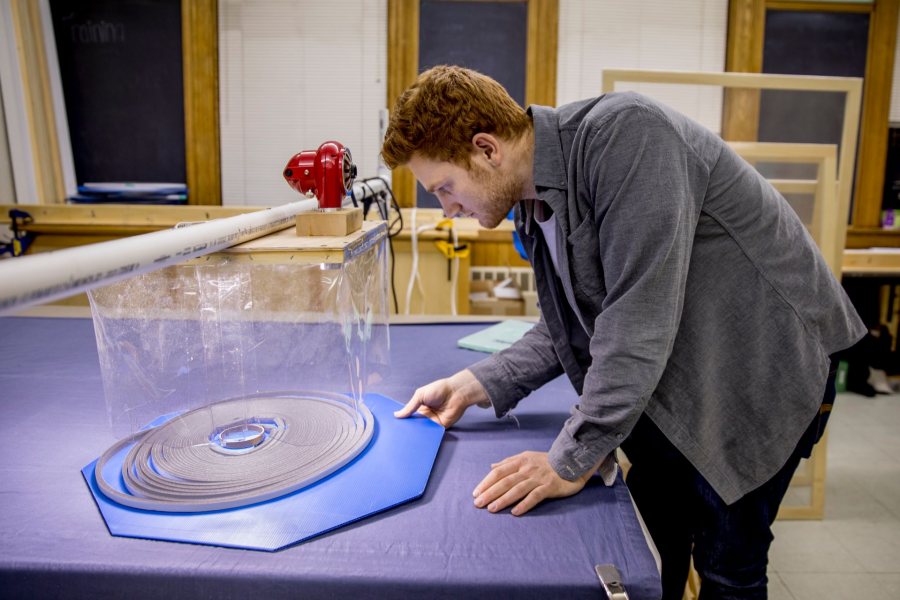

At a Window Dressers community workshop on Nov. 29, community members along with Bates students, faculty, and staff assemble window inserts at St. Mary’s Nutrition Center. The workshop was one part of an semester-long environmental studies project for three Bates students. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Three Bates students — Grace Ellrodt ’20 of Lenox, Mass., Newell Woodworth ’19 of Lambertville, N.J., and Griffin Golden ’19 of Riverside, Conn. — moved among the different stations, answering questions, giving instructions and, in the process, helping to solve a knotty problem for Window Dressers, the nonprofit behind the inserts.

Based in Rockport, Window Dressers has saved Maine residents, from Berwick and Blue Hill to Wells and Wiscasset, upwards of $2.2 million in heating fuel. To keep the inserts inexpensive, the nonprofit asks purchasers to volunteer at community workshops to assemble them. Window Dressers operates in towns all around the state; this year was the first that it had a workshop in Lewiston.

A Window Dressers insert might run between $25 and $50, depending on the window size. The insert pays for itself in a couple of years due to energy savings, and it’s certainly cheaper than replacing a window — but the demands of time and money still put the inserts out of reach for many low-income families.

Window Dressers’ goal is to give 22 percent of its inserts to “special rate” participants at free or reduced cost, but recruiting these participants, and seeing them through from recruitment to installation of the inserts, has proved challenging.

Newell Woodworth ’19 works with a community member to wrap a pine frame with polyolefin film. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“We wanted to know what we can do to change our process to better meet the needs low-income households,” said Laura Seaton, director of community workshops.

Seaton turned to Francis Eanes, a visiting assistant professor of environmental studies at Bates who, with biology lecturer Karen Palin, is teaching a community-engaged environmental studies research course.

Required for all ES majors and one of dozens of community-engaged courses supported by the Harward Center, the course combines academic research with collaborative work in Lewiston-Auburn. In small groups, students complete semester-long projects ranging from building a rental property database to creating a visual history trail along the Androscoggin River.

To Eanes and Seaton, the twin tasks of making the inserts more accessible to low-income families and establishing Window Dressers in Lewiston sounded like a great project. Ellrodt, Woodworth, and Golden got the job.

Grace Ellrodt ’20 uses a home-made dispenser to apply tape to the insert frame. The tape is then folded onto the polyolefin film to secure the film to the frame. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The group had two objectives: help Kristine Corey, the AmeriCorps volunteer in charge of bringing Window Dressers to Lewiston, recruit participants and run community workshops; and, through interviewing participants and workshop coordinators, determine the incentives and barriers to participating in the Window Dressers model.

At first, Ellrodt said, the group tried to talk to potential special-rate participants by setting up formal interviews. That turned out to be unfeasible.

“People have a million and eight things to do, and inserts are the last thing,” Ellrodt said.

Instead, the students went to St. Mary’s Nutrition Center during its food pantry hours, and a staff member introduced them to pantry clients, emphasizing that the window inserts were free. That yielded several participants, who in turn referred the students to still more participants.

Griffin Golden ’19 heats foam weatherstripping before applying it to the edges of the window inserts. The weatherstripping creates a snug fit for the window inserts. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In the end, the community engagement (recruiting participants) and the research (asking about the barriers and incentives to participating) happened simultaneously.

“If you’re no longer the person advising — you’re just sitting and saying, ‘You tell me your experience with inserts, and I’ll tell you what we offer and how those align’ — it’s better,” Ellrodt said.

Over the course of the semester, the group helped recruit 35 participants, going to their homes to measure windows and signing them up for shifts at the community workshop. Bates students, faculty, and staff also helped fill out the ranks of volunteers.

At the second workshop shift, Auburn resident Claire Poirier and her sister, Lise Schulze, worked together to attach double-sided tape to the window frames before another group wrapped the frames in plastic.

The apartment building where Poirier lives with some of her children and grandchildren can get drafty, she said.

The inserts would “be a really good heat saver for me, because my windows are wicked old and it’s too expensive to replace them,” she said.

Griffin Golden ’20 and a community member move through the process of finishing window frames with weatherstripping. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

From participants’ stories, Ellrodt, Woodworth, and Golden began to identify reasons why people would sign up for inserts and help build them, and reasons why they wouldn’t or couldn’t. They laid them out for Window Dressers staff and volunteers, as well their professors, in a presentation in early December.

The incentives for participating — lower heating costs, the ease of getting to the Nutrition Center for the workshop, rave reviews from family and friends, the fact that the inserts don’t damage windows — were numerous.

Also numerous were the barriers. Some participants didn’t speak English; others felt uncomfortable getting the inserts without landlord approval; still others couldn’t attend a workshop because of work or childcare conflicts.

As they recruited participants and measured their windows, the team was able to “convert a lot of these barriers into incentives,” Ellrodt said.

Camille Parrish (right) and Lisbon Falls resident Val Cargill wrap a pine frame. Parrish is a lecturer and learning associate in Environmental Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

For example, some people did not speak English, but it was easy to label the inserts in other languages. In other cases, people were reluctant to sign up because they didn’t have vehicles to transport the inserts home from the nutrition center.

“We saw that coming, so we ended up transporting 80, 90 inserts to people’s homes instead,” Ellrodt said.

The team also recommended strategies local coordinators could use to recruit special-rate participants: Ask a trusted community partner to introduce Window Dressers volunteers and emphasize that the inserts are free. Hold the workshop in a familiar location close to people’s homes, and offer varied and flexible shift times. Put a special-rate section on the Window Dressers website.

Train volunteers one-on-one with physical demonstrations so that knowing English isn’t necessary to participate, or get family, friends, or volunteers to translate. (Val Cargill of Lisbon Falls, a workshop participant who came to the presentation, volunteered on the spot to interpret for Spanish and Portuguese speakers.)

Seaton said some local coordinators in other Maine towns will start using the Bates students’ suggestions right away.

Grace Ellrodt ’20, Griffin Golden ’19, and Newell Woodworth ’19 present the findings of their semester-long research project to an audience of Window Dressers staff and volunteers, community workshop participants, and Bates students and professors at Lewiston Public Library on Dec. 6 . (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Working with them “was a fantastic experience,” she said. “They were really thoughtful about how to set up the project; they offered great suggestions; they were incredibly committed, and followed through with everything.”

“One of the fantastic things about community-engaged learning programs and Window Dressers is that it gives you a really meaningful local, personal action to do,” Seaton added. “Students develop personal relationships with these families, they see the need, and they’re able to make a meaningful difference in these families’ lives.”