In 18th-century Great Britain, honor was a big deal no matter your gender or social class. If you gossiped about the sexual improprieties of a woman, you might find yourself in front of an ecclesiastical court. If you impugned the honor of a male aristocrat, you could have a duel on your hands.

Over the past two centuries, Britain’s reputation-bound society has evolved into a landscape of defamation law that struggles to balance the historic importance of reputation with free-speech ideals. The result? A system where it’s much easier to win a libel or slander lawsuit than it is in most other Western democracies.

Associate Professor of History Caroline Shaw works with Ursula Rall ’20 of Kent, Ohio, during Shaw’s course on sex, gender, and modern cities. Shaw received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to research a book on the history and importance of reputation in Britain. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Supported by a $60,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Associate Professor of History Caroline Shaw will tell the story of reputation in Britain over the past 200 years. The book she is planning will pay especially close attention to defamation, the legal charge of harming someone’s reputation — what the damaging language might consist of, who’s being defamed, and what everyday cases can tell us about British society.

“There are big questions in British history about the degree to which the aristocracy retains control long into the 19th or the 20th century,” Shaw says. “It’s about who has control and transparency. There’s also a gendered story, which comes along with class.”

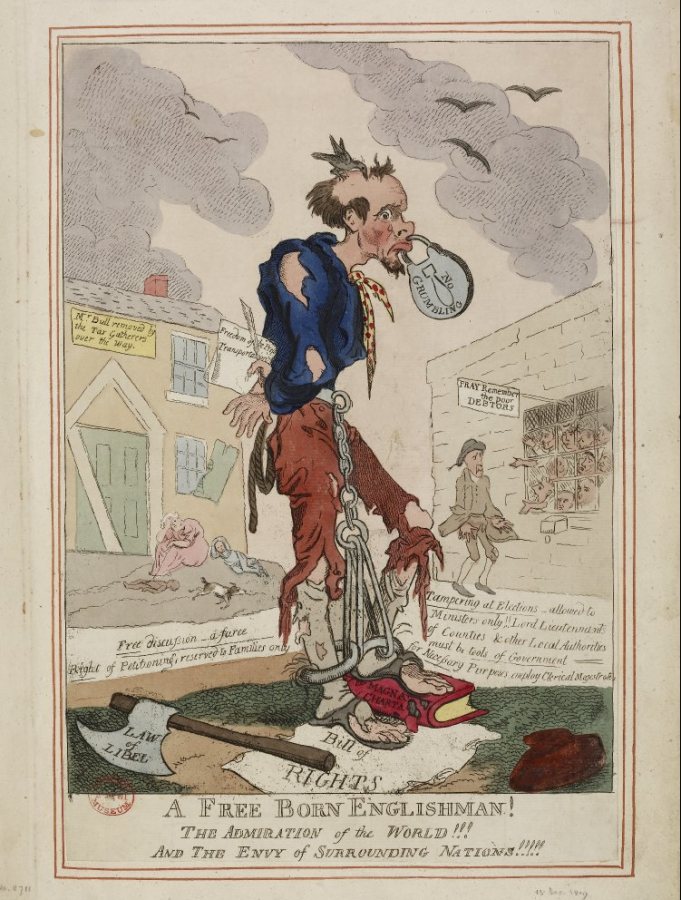

Under the NEH grant, Shaw will take several trips to the U.K. next year for research — looking at everything from newspaper articles and political cartoons to etiquette manuals and legal documents — to better understand how both British law and everyday Brits understood reputation. And, as a visiting scholar at Harvard’s Center for European Studies, she’ll draft parts of her book.

Through the mid-1800s, the Church of England operated ecclesiastical courts for victims of gossip or slander; elite men would often just resort to a duel. As British society became more liberal, and church authority came under scrutiny, secular courts took over.

British society grappled often and publicly with the tension between freedom of speech and the right to reputation. In this 1795 political cartoon, possibly related to a pair of laws restricting public meetings, a man‘s mouth is shut by a padlock reading ”No grumbling.” (The British Museum)

Around the same time, growing ideals of freedom of the press protected emerging newspapers, which gave potentially libelous writing greater reach. But concerns for reputation remained high, and jurists, lawmakers, and thinkers had to grapple with whether gossip could still cause substantial harm to an individual.

In some ways, they decided it could. In 1891, Parliament passed the Slander of Women Act, which made it easier for women to win damages in slander cases that involved accusations of unchastity — because, it was assumed, women were more likely to suffer real harm from such accusations than men.

One of Shaw’s favorite cases is Jones v. Jones, a 1916 case that made it to the House of Lords, which functioned as Britain’s highest court. A Welsh woman, Ellen Jones, falsely claimed that David Jones (no relation), the headmaster of a school, had had an affair with a school employee. Mr. Jones lost his job and sued.

“Embedded in all of this is a running concern of, should gossip even really matter?”

Jones couldn’t prove to the justices that ladies’ gossip caused him material harm. He lost his cause, but not before the House of Lords weighed whether a man who found himself in similar predicaments to the maligned woman’s ought to be protected by the law.

“It’s a hinge moment in which this very patriarchal use of the law is met by a more democratic possibility of a law,” Shaw explains. “Embedded in all of this is a running concern of, should gossip even really matter?

“In a liberal society, from the vantage point of the ‘self-regulating, independent male,’ gossip is relegated to the background,” she adds. In that context, authorities assumed that “such a person should be independent of the community.”

As the 20th century wore on, fewer people brought suits under the Slander of Women Act. Still, the damaging power of gossip remained salient, and the law stayed on the books until 2014.

In the meantime, a new set of questions related to reputation emerged. These included the rights of celebrities to privacy when tabloids are flourishing; whether defamation law can be applied to hate speech in an increasingly multicultural Britain; and what protections, for example, the American publisher of an unflattering biography has in Britain, where it’s much easier to win a defamation case than in the U.S.

Such “libel tourism” — when someone sues for defamation under British law because it’s easier to win, even if the plaintiff only has the most tenuous connection to the U.K. — puts the tension between reputation and free speech in clear relief, Shaw says.

In the 1930s, MGM Studios made a movie about the death of Rasputin, a famous figure in Russian history. The film contained a completely made-up scene in which a princess is seduced by Rasputin. The Russian princess, still alive, successfully sued the American company for libel in British court.

“There’s what they call a chilling effect on publication, because of the fear of libel tourism,” Shaw says. “The anxiety of that ticked up by the 1980s.”

More recently, lawmakers have worked to tip the reputation-vs.-speech balance in favor of speech. “The desperate hope was to curtail these cases,” Shaw says.