As they amass a body of work to show in Bates’ Senior Thesis Exhibition, what are some of the big lessons for this year’s studio art majors?

There are practical skills: Planning and time management. Understanding when to experiment and conceptualize — and when to cut to the chase and start producing. Learning to see through the eyes of people you hope to communicate with.

The 2019 Senior Thesis Exhibition artists talk about their work.

But there are also “softer” takeaways whose value, in fact, may surpass career considerations and play directly into life satisfaction.

There’s the power of consultation, companionship, and collaboration, for example. “Especially in the first semester, we spent a lot of time looking at each other’s work,” says Flannery Black-Ingersoll of Concord, N.H., one of the 14 senior artists in this year’s exhibition, which opens April 5.

“That’s very instructional, both for how you look at your own art and what you ask questions about, but also building that camaraderie in the studio space,” she says, meaning the Olin Arts Center studios that are each shared by several students. “‘Okay, what do you think of this?’ ‘Is this ridiculous?’ ‘Do you have any ideas?’ — sort of feeding off each other.

Flannery Black-Ingersoll at work in her Olin Arts Center studio on March 20, 2019. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“It’s this nice bubble of artistry, which people look for beyond college.”

And then there are the lessons that are basically good for one thing, but a highly important thing: a laugh. Stuck at one point in her work, which involves fabric, ceramics, paint, and wood, Black-Ingersoll was inspired to try to integrate cheesecloth into the concept.

For her and studiomates Jo Cunningham and Daisy Diamond, cheesecloth was The Answer — until it wasn’t. “It was late at night,” says Black-Ingersoll. “We were all freaking out because we just had this genius moment. But of course it didn’t happen.”

That’s because she subsequently heard that a thing for cheesecloth is a typical developmental stage for first-year art school students. “So I didn’t end up doing that.”

At top, Daisy Diamond works with art, steel, and fabric in her Olin studio. At left, Grace Link ’19 hangs her photographs with help from Haley Crim ’19. At right, Mickai Mercer ’19 places his drawings in the art museum’s Upper Gallery. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Pamela Johnson, associate professor of art and visual culture, advised the senior artists during the winter semester, and Penelope Jones, visiting assistant professor of art, was the fall semester adviser.

2019 Senior Thesis Exhibition artists

+Flannery Black-Ingersoll ’19

Formalism and craftsmanship are important in Black-Ingersoll’s artwork. Generally speaking, she makes two types of structural forms — quilted canvas wall hangings and wooden structures incorporating ceramic vessels and painted canvas — that both take abstracted nude self-portraits as subjects.

“I am not interested in developing sexualized imagery” Black-Ingersoll says, but instead focuses on the human form as it appears in visual art and dance. She sketches, paints, and embroiders figures in a way akin to choreography. “In contrast with the ephemerality of dance, these figures have permanence,” she says. As she does in her choreography, Black-Ingersoll infuses her art with humor and a sense of rebelliousness. “There’s something comical to me about depicting the nude female with embroidery,” she says.

A detail from “Quilt — Posture Pattern” (2019), a piece in acrylic paint and embroidery on canvas by Flannery Black-Ingersoll ’19.

+Jo Cunningham ’19

Cunningham of Brooklyn, N.Y., confronts her own discomforts and anxieties in her paintings. Painting saggy skin and baggy eyes gives her the opportunity “to explore a level of darkness and discomfort in the safety of the abstract and the fantasy of paint.” She often paints babies, which “have the saggy skin, puffy eyes and disproportionate bodies that I love” — but “they are important. The creation of them and their appeal is fascinating to me.”

Because babies represent human potential, they are precious. Cunningham’s paintings “explore the complexities of being this precious captive, and the discomfort of childhood.” She depicts scenes where babies run amok, driving cars, lassoing cows, and creating general chaos. Her work is meant to unsettle and disturb. “The material and process are beautiful, but like artist Ida Applebroog said, the finished product is not meant to hang over the living room couch,” she says.

“Home Free” is a 2019 oil painting on canvas by Jo Cunningham ’19.

+Sarah Daehler ’19

Ceramicist Daehler of Greensburg, Penn., aims to make vessels that will be valued “for their texture, beauty, and utility,” she says. She places high value on craftsmanship: “The pieces I am most attracted to are ones that do not easily reveal their process,” and Daehler strives to remove or conceal such evidence of pottery technique as throwing lines or fingerprints.

She’s also acutely conscious of the user experience, making vessels that are lightweight and a pleasure to handle. “Tactile sensation is an important part of my work,” she adds. She uses slip-trailing to speckle the surface with raised dots in random order. Inspired by the clean designs of Frank Lloyd Wright, Daehler glazes with white, which affords attractive effects of shadow and light, or with deep blues that allow “my slip-tailed dots to peek through, like stones peeking out of the water in a shallow stream.”

Untitled white stoneware (2019) with blue and white glazes by Sarah Daehler ’19.

+Daisy Diamond ’19

With the goal of confronting systemic privilege and oppression, “I think about my sculptures as representations of invisible frameworks: penetrable webs of histories, symbols, and identities,” says Julia “Daisy” Diamond of Bala Cynwyd, Penn. Using sutures as a motif in pieces that also incorporate steel, fabric, clay, wax, thread, and animation, “I want to understand and deconstruct my privileges, especially my whiteness, as historically created and maintained by violent assemblages of sutures.”

Her sculptures, says Diamond, “represent the way that whiteness is constructed by thousands of moments, stitches of affirmation, wobbly and waiting to unravel.” But the sutures have more than one meaning. “The process of confronting myself in my work is not an easy, pain-free, linear process,” she explains. “Sutures are a recurring visual element that I use to represent this experience as a step of healing.”

A detail from “lady / of the sutures, / wobbly to the touch, / she was anxiously stitched into a complicit soldier / for when / time would not cleanse these wounds” by Daisy Diamond ’19. The 2019 sculpture incorporates steel rods, fabrics, and wire.

+Meha Jhajharia ’19

“Using drawing and building as a liberatory practice,” Jhajharia of Kolkata, India, makes objects that he calls “headspaces.” Constructed from everyday materials such as cardboard, wire, and beads, these miniature spaces invite the viewer to peer inside. “The interiors are both intricate and methodical, urging the viewer to explore the details and construct the hidden narratives,” he says. “Depth, perception, and light combine to challenge the reality of what is being viewed.”

Creating physical space is important to Jhajharia, who struggled to find his own place as a queer trans South Asian boy. “It was natural that the work I wanted to create took up the radical act of explicitly embodying myself,” he says. “Each headspace that I have made is significant to an experience I have lived, and each structure holds thoughts I have actually had.” He asks his viewers to “be ready to reject an apolitical approach and instead challenge their beliefs on gender, race, caste, and societal norms.”

The interior of “Headspace 2” (2018) by Meha Jhajharia ’19. The media in the piece include cardboard, reflective sheet, plastic crystal buttons, Scotch-Brite metal scrub, and Christmas ornaments.

+Lily Kip ’19

Kip’s oil paintings were born out of agitation and insight dating back to a time abroad, during which she missed nature in New England and felt alienated from her art-marking. Back at Bates, Kip of Needham, Mass., began a series of self-portraits with plants, but wasn’t satisfied with those. Her current approach emerged when a friend advised her to “paint people holding the plant.” This suggestion proved to be an effective way forward.

Humor is essential to the paintings, as is an appreciation of color. Along with bordering each of her portraits with a golden arch in the manner of an illuminated manuscript, Kip chose background colors corresponding to the relationship between painter and her subject. “Color is critical to my conception of character, the same way that comportment or clothing can capture the essence of a person,” says Kip.

An oil painting on plywood panel from “Growth Cycle Altarpiece” (2019) by Lily Kip ’19.

+Morgan Lewis ’19

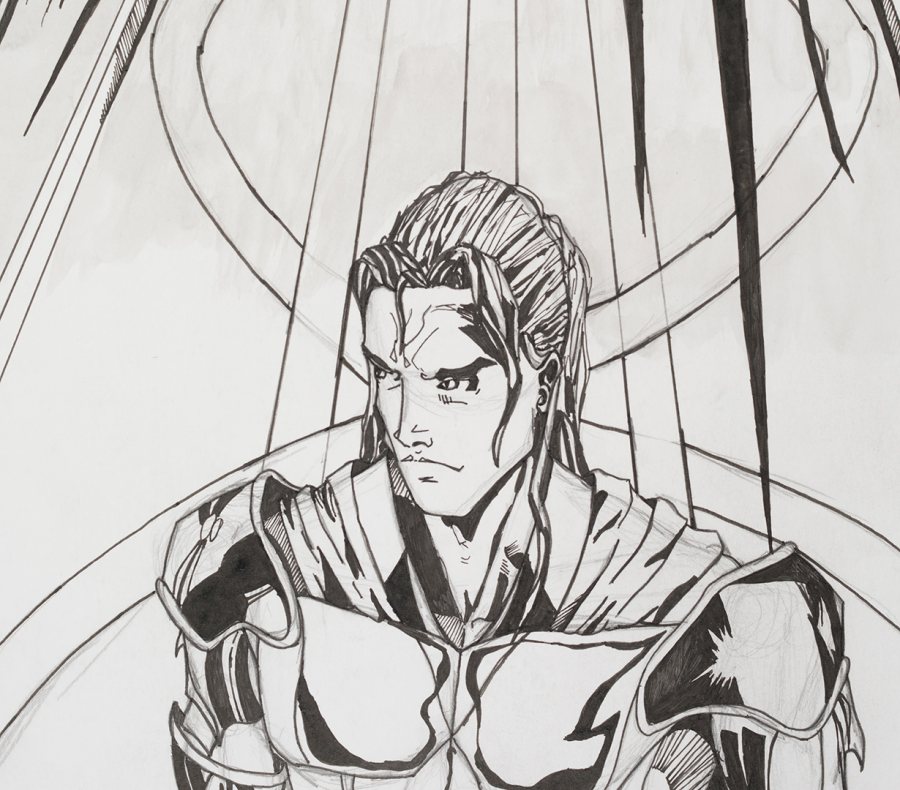

Lewis’s drawings stem from his love for comics. “I strive to emulate the dynamic movement that I see on these pages and craft an engrossing narrative,” says Lewis of Nederland, Colo. “In my work I try to build new worlds that capture views of different kinds of space. Through the use of deep blacks and stark whites, I hope to create dynamic and eye-catching pieces that call for a closer look.”

Lewis doesn’t feel attracted to the ironic and cynical school of comics. In comics, “we see characters rise from tragedy and undergo many trials and tribulations throughout their lives. However, no matter how bleak these stories may seem, the message that they consistently send is that there are always good people in our world,” he explains. “When I was younger, I wanted to be Superman because I wanted to be strong and impervious for its own sake,” he adds. “A few years later I realized that there was an additional reason: He stands for hope.”

A 2019 drawing in micron pen, sumi ink, pencil, and Bristol paper by Morgan Lewis ’19.

+Grace Link ’19

Link’s love of photography started with her first digital camera at age 10. Now she works exclusively in black-and-white film, finding that both the limitations of film and “the physical control that I have over image processing make me feel like I am creating art pieces instead of mere renditions of digital files.”

In the Senior Thesis Exhibition, Link of Montclair, N.J., is showing portraits of young adults. Most of the images are studio portraits taken against a plain background. “My goal is to present the emotions I see in each person in a short period of time,” she says. The subjects, friends and strangers alike, choose to be photographed by Link by signing up online, which gives her the comfort of consent. “This develops trust between the subject and myself where I can respectfully represent them,” she says. “I want the hidden power of each person to be present in my portraits.”

The silver gelatin print “Haley” (2018) is a portrait of Haley Crim ’19 by Grace Link ’19.

+Mickai Mercer ’19

“Ever since I could first pick up a pencil, I was drawing on newspapers, books, Bibles, and any other type of paper I could get my hands on,” says Mercer, a Philadelphia resident. “My Nana got so irritated with me drawing on everything that she brought me my first sketchbook and took me to a museum.”

“Concepts of life, death, manifestation, human will, metaphysical space and experiences that can be relatable for everyone became the main topics I explore,” he explains. Mercer depicts his own face, plants, ravens and crows, wolves, and butterflies, viewing the animals as extensions of himself. Each image “attempts to allude to a thought, emotion, or a shared experience,” he says. Through a variety of media, subjects, and styles, Mercer has found ways to fully “dive into this world of mystery and infinite possibilities.”

“Plumas y Aleteos, Feathers and Flutters” is a 2019 drawing in graphite, charcoal, and ink on paper by Mickai Mercer ’19.

+Hawley Moore ’19

Erica Hawley Moore’s interest in depicting drawing, painting, and sculpting hands began as a challenge. “The hand is widely regarded as one of the more difficult body parts to depict,” says Moore of Ho-Ho-Kus, N.J. Her foray into creating hands is neither easy nor comfortable. “I tend to bounce back and forth between looking for meaning in this work and then deciding that it’s not necessary to do so,” she says. Ultimately, her discomfort allows her to create disjointed pieces that “do not have to make sense to be complete.”

“I am making broken hands, pieces of hands, whole hands, hands linked together, hands alone, hands forming shapes, and hands in blank space. I have removed context from my work, to allow more focus on the form itself,” she says. “I have noticed more and more how crucial they are to my practice and how my appreciation for them has grown.”

A recent untitled work in plaster, acrylic, and wood by Hawley Moore ’19.

+Abby Lynne Kizirian Myers ’19

“My fascination with dragons is lifelong and deeply personal,” says Myers of Pawtucket, R.I., who has found inspiration in mythology, folklore and the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. In her installation “Broodmother,” she explains, “I’m investigating how my agency as an artist, a woman, and a feminist subverts the patriarchal and masculine toxicity historically associated with dragon iconography. My manipulation of this imagery effectively subverts that relationship.”

Her installation consists of sculptural objects arranged, in juxtapositions influenced by mountain ranges (the natural lair of dragons), to suggest dragon anatomy. “Fire is an indisputable aspect of dragon iconography,” Myers notes, and she uses heat-worked materials like clay, metal, and glass, and also selects washes and colors to create “a volcanic surface quality,” as ways to evoke expanses freshly scorched by dragon fire.

A detail from the 2019 earthenware piece “Broodmother” by Abby Myers ’19.

+Bailey Richins ’19

As she considered subjects for her paintings, Richins of Westerly, R.I., thought of visits to her grandmother’s house before and after her grandmother moved to a new home. Richins recalled the quality of light and the significance of the objects in the bathroom. “After contemplating what was missing from and what remained of the space, I became aware of a bathroom’s significance as one of the most personally revealing rooms in a home,” she says.

Now she uses representational paintings of bathrooms to “examine how an unoccupied space can be activated by human energy and natural light,” she says. She has a particular interest in the contrast between warm and cool light and how each falls on neutral objects. “With the hope of accurately representing the temperature of light, I challenged myself to ignore what colors I instinctively associate with an object and instead mixed paint to reflect what my eyes actually perceive,” Richins says.

A detail from “Bathroom, second,” a 2019 oil painting on canvas by Bailey Richins ’19.

+Chandler Ryan ’19

Ryan’s portraiture arose from her response to the “male gaze,” the sexual objectification of women in literature and art created by men. It was a phenomenon brought uncomfortably to her attention during her semester abroad in a country where the male gaze is a fact of life in social settings. “To land in a place where I wasn’t even able to meet the unwanted gaze of men on the street shook me to my core,” says Ryan of Delmar, N.Y.

Through her photographic portraits of women, “I subvert that norm,” says Ryan, “as the one doing the looking, with my female subjects presenting themselves and looking back at the viewer.” These images “are my pushback to the ways in which our bodies, and at times presences, do not feel like they are our own.” Shooting on black-and-white film, she says, “my goal is a simple portrayal of women around me whose strength and power is magnified.”

“Josie” (Josie Gillett ’19), a 2019 inkjet print on silver rag paper by Chandler Ryan ’19.

+Anh Thai Tran ’19

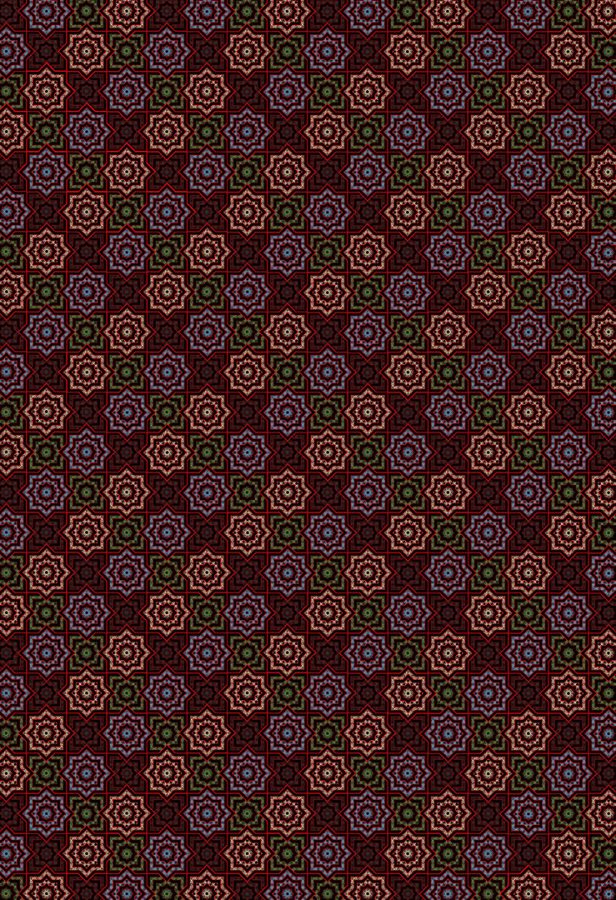

Dynamic, spontaneous, and iterative, Tran’s image-making process begins simply — with a square, circle, or a set of connected lines. “I want to invoke emotions with only simple geometric shapes,” says Tran of Middleton, Mass. “I am drawn to lines and colors by the same curiosity that prompts a toddler to inspect an object for the first time.”

Influenced by the detail and layered effects of Japanese textiles, Tran lays geometric patterns on top of each other in order to create a “sense of wonder.” He also responds to the formal restraint and clarity of commercial wallpaper design, in which he embeds his own emotionality — “visions of futures that will not come, and memories that will not fade.” His work is utilitarian, useful as designs for clothing, screensavers, or even a tatoo. “Art has to serve a purpose: If a piece does not enlighten our mind, it should enrich our surroundings,” he explains.

“Starry Night” is a 2019 digital image on matte paper by Thai Tran ’19.