One class session with rhetoric professor Stephanie Kelley-Romano in 2015 was enough to turn Claire Sullivan ’19 into a rhetoric major.

Sullivan’s first-ever class at Bates, it was the opening session in the course “What Is Rhetoric?”

Kelley-Romano showed music videos by female country artists, including RaeLynn’s “God Made Girls” — which features lyrics like, “Somebody’s gotta be the one to cry / Somebody’s gotta let him drive … So God made girls.”

Kelley-Romano then struck up a discussion encompassing heteronormativity, gender roles, and who’s excluded from a worldview like RaeLynn’s. “She just went off on the absurdity of the rhetorical implications of this music video,” says Sullivan of Montville, N.J. The class “made me want to be a rhetoric major because she just had so much passion and enthusiasm for it.

Stephanie Kelley-Romano leads a “Television Criticism” class on March 6, 2019. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“She emphasized the way we look at certain cultural texts. When you critically analyze them, you get so much more out of them and see their cultural and sociological implications in a really different way.”

Praised as a teacher who’s exacting, empathetic, authentic — and passionate about her field — Kelley-Romano has received the college’s 2019 Ruth M. and Robert H. Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Associate professor and chair of the rhetoric, film, and screen studies department, Kelley-Romano is known at Bates and beyond for her professional focus on topics in the popular consciousness — the rhetoric of television, conspiracy theories, and abductions by space aliens, to name a few. Her biennial course on presidential campaign rhetoric is built around a mock campaign that affords an intensely hands-on, multidisciplinary experience for students.

She has led public workshops on spotting fake news, analyzed for the local newspaper a debate between candidates for Maine’s 2nd District congressional seat (including Jared Golden ‘11, who ultimately won), and, with math professor Meredith Greer, she is modeling how conspiracy theories spread.

“It’s infectious to be in a classroom with somebody who is excited about what they’re teaching.”

“Rhetoric allows us to understand how realities are created,” says Kelley-Romano. “Why we call someone a survivor, as opposed to a victim, matters. It matters who we define as terrorists. The way we criminalize drug use by some but construct it as a health crisis when it affects other people, matters.

“So it’s important to allow students to see that just because something is in a history book or in a newspaper,” that doesn’t necessarily make it true, she says. “Objectivity is a little looser than they may have been led to believe.”

Like Sullivan, it was in her first class at Bates that Molly Chisholm ’17 of Boston first encountered Kelley-Romano. As with Sullivan, the professor’s enthusiasm made a big impression. “It’s infectious to be in a classroom with somebody who is excited about what they’re teaching,” Chisholm says. “You’re automatically engaged because she’s so engaged and so happy to be there.”

Stephanie Kelley-Romano talks with Molly Chisholm ’17, who portrayed a Republican candidate for U.S. president in a fall 2016 campaign rhetoric course. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I love watching students gain confidence and skills,” Kelley-Romano says.

“When I’m trying to teach a critical-thinking skill or to get them to understand the logical organization for a paper — when I see it actually happen, that’s a great feeling. And then to see it again and again, and see the change in them from the beginning to the end, is just so satisfying.”

She adds, “If I honor and respect their process of coming into knowledge and coming into themselves, and just try to help that along, then it gives them so much agency. And they’re so much more invested in doing well.”

In Kelley-Romano “there’s an element of genuineness” that’s uncommon, says Sullivan. “She lets us see who she is as a person.” For example, Kelley-Romano’s sons, 16-year-old George and 14-year-old Richie, are no strangers to Pettigrew Hall (and they also help keep their mother in tune with pop-culture trends).

“In return, she expects us to show her who we are as people,” Sullivan says. “She just cares so much about understanding where her students are coming from and what makes them people, more than just students.”

Kelley-Romano listens to a remark by a fellow faculty panelist during a viewing and discussion of the televised inauguration of President Donald Trump in January 2017. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“She has a great degree of empathy, and I think that’s always present in her pedagogy,” says Kelley-Romano’s colleague Charles Nero, Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies. “If you talk about the importance of care in the process of teaching, Stephanie exemplifies that.”

Some of that empathy may be traceable to Kelley-Romano’s undergraduate experience. A first-generation-to-college student at Emerson University, she took away a certain understanding of the uncertainties, insecurities, and feelings of isolation that can come with being a first-gen. She’s not shy about putting that understanding to work.

Openness about her own experience is a way to help put students at ease with their situations. “To articulate those fears or seeming insecurities and make them laughable, and to own them,” Kelley-Romano says, “makes students feel a lot more comfortable” — helps them “see that on the inside everybody can be silly, or insecure, or uncertain, and that it’s okay.”

None of which is to suggest that she is a pushover. “She wants, probably demands, that her students excel,” Nero says. “She sees her role as giving them the tools to excel, and she thinks a lot about that.

“And I think that when students leave her class, they’re aware that whatever happened — the good, the bad, the ugly — it’s on them. She encourages responsibility.” Nero adds, “I would daresay that she is brilliant as a pedagogue.”

A 2017 graduate, Gabe Nott experienced those high expectations as he honed his senior thesis under Kelley-Romano’s guidance. Now a New York City resident, Nott was writing about the TV program Last Week Tonight, hosted by comedian John Oliver, and the implications of news-focused comedy for civic discourse.

“It took me a while to figure out my argument for my thesis,” says Nott. “Every time I thought knew what angle I was going to take, she’d come back with a question I wasn’t able to answer. Honestly, it was pretty frustrating.

“But, when I finally got there, I realized that all that prodding and pushing helped me craft a more incisive analysis” that even transcended Oliver to shed light on how, Nott says, “we as a country talk about politics.”

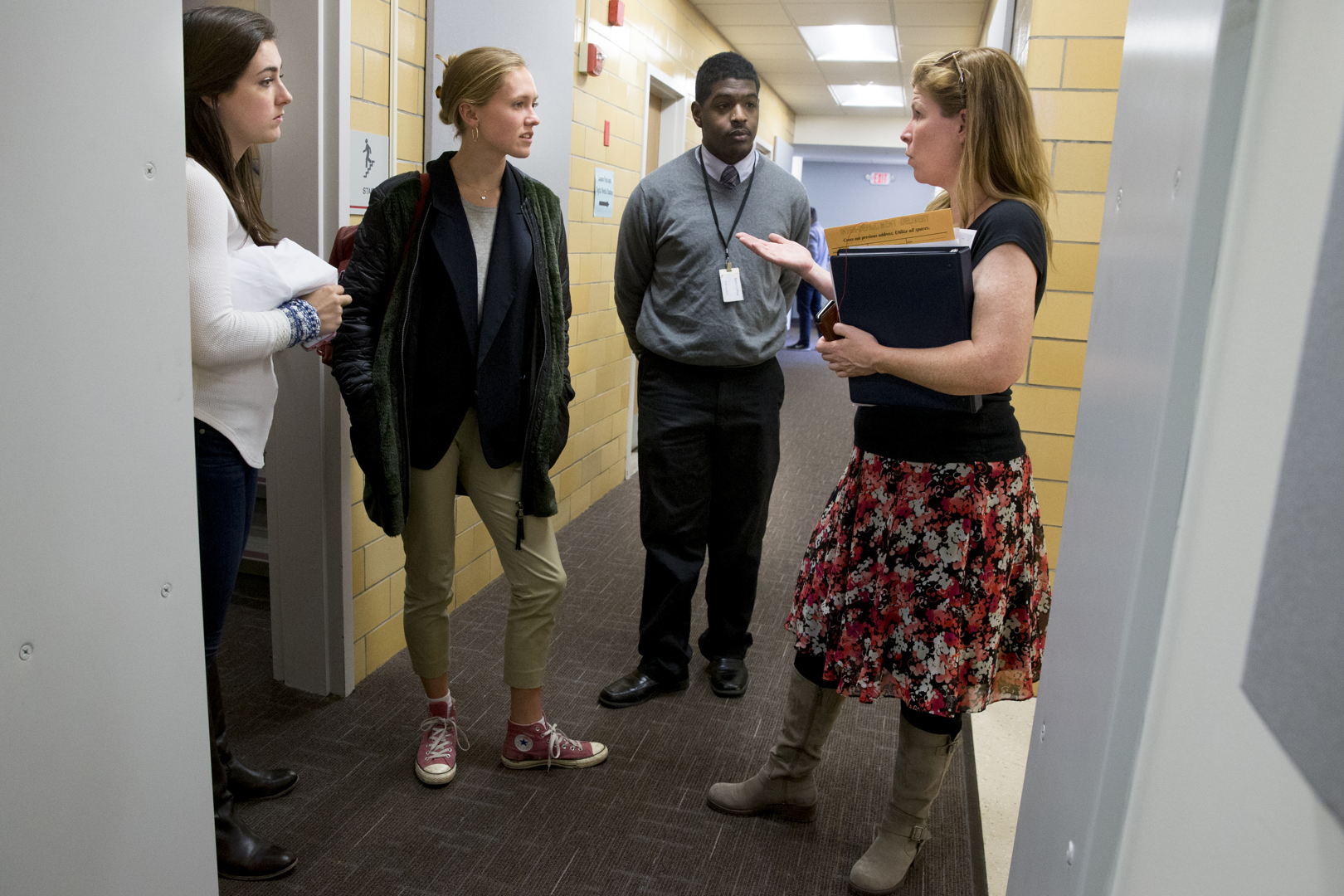

Michaela Britt ’17, Molly Chisholm ’17, and Brennen Malone ’17 confer with Kelley-Romano during the 2016 campaign rhetoric course. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

He adds, “When I finally figured it out, she was as excited as I was. All that just made me feel like she was really invested in helping me become the best scholar I could be.”

Sullivan took the fall 2018 edition of Kelley-Romano’s campaign rhetoric course. The mock campaign involves students in just about every aspect of a campaign that involves communications — which is pretty much all of it, from developing a platform to writing ads and speeches to holding debates to mounting a crisis response.

“The mock campaign felt so practical,” says Sullivan, who played the role of the Democratic vice presidential candidate. She plans to work for a real campaign after graduation as a prelude to a career in law or politics. “She expected a professional quality of us, and so it felt like we were running a real campaign.”

She adds, “It allowed us to really think about how political campaigns craft narratives, which is obviously a huge part of the study of rhetoric.”

The fictional presidential candidate for the Democrats was a military veteran, as was his wife. “He was Jewish, and so we talked about his Jewish identity a lot. We made my character queer and married to a woman.”

Rhetoric professor Stephanie Kelley-Romano meets in her office with Kathryn Carew ’17 of Falmouth, Maine, in 2016. Carew and Kelley-Romano published her senior thesis, a study of Donald Trump and the “birther” movement, in the Journal of Hate Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Sullivan says, “It got us thinking about how we talk about identities, and how those identities are perceived and portrayed to a greater public.” Developing candidate personas — their backgrounds, beliefs, relationships — reflected an important emphasis in the Bates approach to teaching rhetoric: an understanding of intersectionality, how different aspects of identity relate to one another and how they are treated in communications.

“Our focuses on gender, race, sexuality, and ethnicity are crucial organizing principles to our major,” Nero says. “Stephanie has been fundamental in the creation of that.”

Four years after the RaeLynn revelation, Kelley-Romano advised Sullivan on her senior thesis, which looks at the role of conspiracy rhetoric in the Fox News coverage of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings — a research project they hope to publish together.

The relationship has meant a lot to her, Sullivan says. “To have somebody who has known me throughout the entire four years, academically and a little bit outside the academics, has been a very comforting experience.” Even after Bates, “I know that she’ll really be there for me.”