I became a cop on a lark.

In 1968, our class entered Bates through a shifting portal of immense social change. Already traumatized by the deaths of JFK in 1963, we lost Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy in April and June.

The week before we moved in at Bates, Chicago police beat war protestors senseless at the Democratic National Convention.

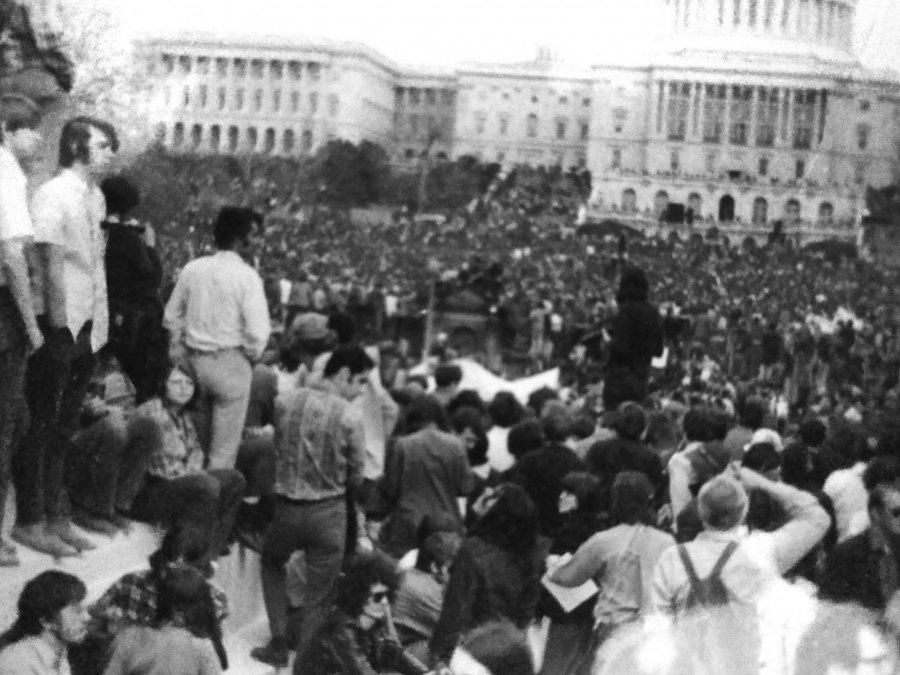

In April 1971, I marched against the Vietnam War with 500,000 others in Washington, ready to enroll in McGill University if my conscientious objector application was rejected. Fortunately, they called up men with draft numbers from 1 to 100; mine was 153.

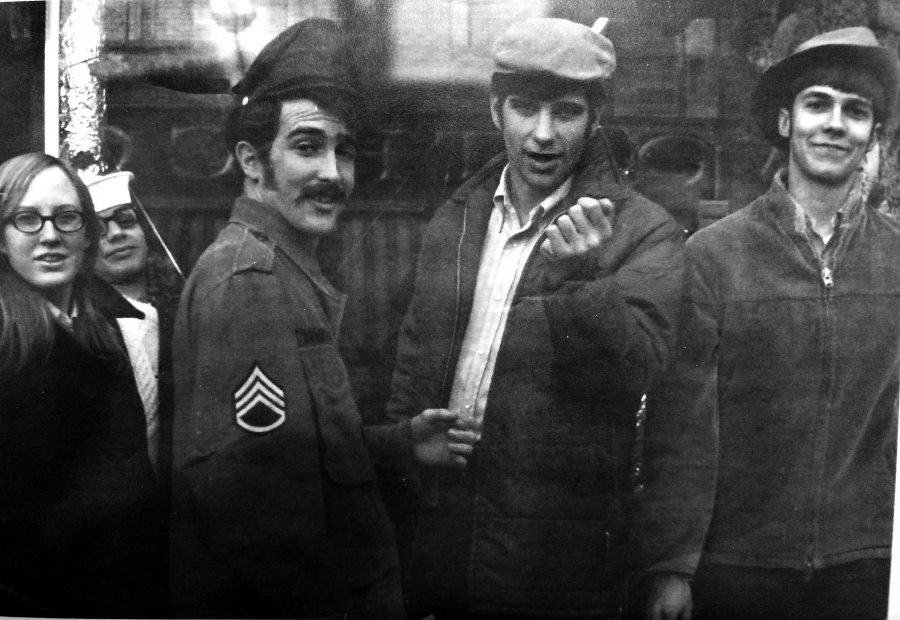

Circa 1969 downtown Lewiston, Mac Herrling ’72 (second from right) poses with, from left, Jackie Kopco ’71, an unidentified friend, Ted Barrows ’71, and Ned Ayers ’72. (Photograph courtesy of Mac Herrling)

I wrote my senior thesis on the Black Power movement after working and learning in Spanish Harlem during Short Term, where we witnessed first-hand the effects of our racist society on a community.

By the time of our graduation in 1972, we had replaced Shakespeare with experimental guerrilla theater; Haffenreffer with weed, speed, and LSD; wait-’til-marriage with free love; and Hair became a musical because none of us cut any of it anywhere on our body.

Back then, living on campus was like living in the Forbidden City. We ventured out for a draft at the Blue Goose, to cheer strippers at the Manoir Hotel, to pick up girls, and bum rides to concerts. We surfed for bohemian clothing at Goodwill and picked up posters and pipes at The Grand Orange.

But that was about it. On campus, maids cleaned the men’s rooms, workers served our food, and others secured the perimeters of our cocooned existence. We were clueless about life in downtown Lewiston and Little Canada.

Working as a Lewiston summer patrolman — my first job as a Bates graduate — seemed a good way to get clued in. Idealistically, I probably wanted to see “the Revolution” from street level before hitch-hiking the country or backpacking through Europe.

Mac Herrling took this photograph of protestors gathered on the National Mall during the historic April 1971 protest against the Vietnam War.

So it was that in the summer of ’72, the city of Lewiston hired five of us — me, Tom Carey ’73, and fellow new Bates graduates Jay Scherma, John Sninsky, and Gerard Williams — as temporary summer patrolmen.

Publishing a photo of us that June, the Lewiston Evening Journal reported that we were hired to “make it possible for the department to meet its commitments during the summer months, while regular members are taking vacations.” It was a time of tension over police pay, and some believed we were brought in to deny regular patrolmen summer overtime pay.

Our training also included spending time sitting in a small trailer with cannabis burning so we would know what it smelled like.

Our few days of “training” was a sign that my real education was about to accelerate. We chit-chatted with Deputy Chief Laurent Veilleux, watched antiquated police training films, and, for one afternoon, learned to shoot our Smith & Wesson .38 caliber revolvers at a local sand pit.

Sninsky, who had been my Bates roommate, recalled that our training also included spending time sitting in a small trailer with cannabis burning so we would know what it smelled like. Said Sninsky, “We just smiled!” Then they let us loose on the downtown streets like a litter of untrained puppies.

By 1972, it felt that the world was bypassing Lewiston. For a newly minted college graduate, his head stuffed with critical realism, Émile Durkheim, and the poems of Dylan Thomas, it was a rude awakening to live and work in Lewiston.

The mills that once pumped out textiles and shoes were becoming empty brick mausoleums. Lower Lisbon Street had become infamous, particularly after dark. Drugs were just arriving but everyone we met on the street after hours seemed to be drunk, trying to get drunk, or had passed out.

We arrested alkies and made them sleep it off. A staggering, bleeding man greeted me my first day on the job, so I learned about first aid, trauma care, veteran’s services, and social work all in one encounter. Abortion was illegal but domestic violence was not. I tended to women who were beaten and desperate to get away.

This photograph, published June 16, 1972, in the Lewiston Evening Journal, shows Deputy Chief Laurent Veilleux (left) instructing the police department’s summer patrolmen-in-training Tom Carey ’73, John Sninsky ’72, Gerard Williams ’72, Jay Scherma ’72, and Mac Herrling ’72.

We ignored prostitution being transacted at the bus terminal and happening in our midst. My fellow officers were not immune to misbehavior. One unfortunate patrolman kept his microphone open while he carried on a tryst in his cruiser.

We were paired up with regular officers, most of whom were professional and seemed to appreciate our help. Sninsky recalls following an officer into a bar to help break up a fight. “He said he was surprised that I followed him even though I was just a ‘college kid.’ I said that I wore the same blue uniform and it was my responsibility. I think he was impressed.”

We enjoyed the benefits — some illicit — of being peace officers: hot donuts fresh off the Country Kitchen bakery conveyor belt and free coffee and food from merchants. I found a new girlfriend by looking up her registration plate on the system after she drove ‘round and ‘round my downtown beat. It was a different time.

By October, my stint was over. I was ready to share newfound street epiphanies and a chastened revolutionary fervor on a larger stage. I worked as an inner-city journalist reporting on the lives of people similar to the ones I encountered on Canal Street and, after a career change, returned to Maine as a school social worker eager to listen to the broken and disheartened.

In the years since that summer, Lewiston has changed in unexpected and graceful ways, embracing a revival brought on partly by an influx of immigrants from African nations. But I can still get pickled eggs with my draft at The Goose. And Bates is an integral and important influence in the transformation.

I think I’ve changed, too, making my own peace with the chaos and upheaval of the early years. On a May night back in 1972, shortly before our graduation, my classmate Steve Hoad said, “The dogs of the past are nipping at our heels.” I’ve given them a good chase, befriended them, and let them pass me by. The present is enough.

And although I’m not a Mainer by birth, I am fitting in a bit more. As a school principal once said to me, “You’re pretty down-to-earth for a Bates guy.”

Maybe my improvident choice to be a fledgling cop has finally paid off.

Mac Herrling ’72 lives in Bradley, Maine.