It’s safe to say that whoever is running the Bates–Morse Mountain Conservation Area (and, nearby, the college’s Coastal Center at Shortridge) has a lot on their plate.

Any director of the site has “to have their eye on student learning, faculty engagement, and coastal research,” not to mention “what signage is needed to keep dogs off the beach,” says Darby Ray, who as head of Bates’ Harward Center supervised the conservation area director for a number of years.

Since 2008, that director has been Laura Sewall, who is retiring this summer, to be succeeded by marine scientist Caitlin Cleaver, who starts work on Aug. 16.

“Laura has been a tireless advocate for Bates–Morse Mountain,” says politics professor Áslaug Ásgeirsdóttir, an associate dean of the faculty who now oversees the area’s management. “She has been incredibly creative and enthusiastic about working with our faculty and students who do research there.”

With Seawall Beach in the distance, the Sprague river and marsh are shown from the summit of Morse Mountain. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

In its 600 acres located about an hour from campus on the Phippsburg peninsula, Bates–Morse Mountain incorporates two salt marshes, two rivers, a rare stand of dune pitch pines among its many trees, and the eponymous small mountain. Accessed through the conservation area but not part of it is Seawall Beach, a real beauty that’s the last undeveloped barrier beach in Maine.

Bates–Morse Mountain is owned by a nonprofit corporation, protected in perpetuity from new development, and managed by Bates under the eyes of The Nature Conservancy, which holds conservation easements on the area.

It’s valued by locals and tourists for its beauty, and by scientists, including several from Bates, as a place to observe how diverse ecosystems are responding to unprecedented natural change.

“Laura has, with great finesse and diplomacy, balanced the needs and interests” of those stakeholders, says Ray, and in doing so has given the research mission primacy at Bates–Morse Mountain.

Laura Sewall, who retires this summer as director of the Bates–Morse Mountain Conservation Area, observes the area from a small plane in June. (Brittney Lohmiller for Bates College)

A writer who holds a doctorate in visual psychology from Brown University, Sewall has deep family roots in the peninsula. A former professor at Prescott College in Arizona, she is the author of the book Sight and Sensibility: The Ecopsychology of Perception (1999), which her publisher describes as “the first definitive guide to the new field of ecopsychology.” She has also served as a lecturer in environmental studies at Bates.

Sewall’s retirement plans include more book work. She wants to finish a volume on perception that until now has been relegated to her spare time. In addition, encouraged by interest from an academic publisher, she’s working with Bates faculty and alumni on a compilation of research from Bates–Morse Mountain. That’s where we start our interview.

Who are the faculty taking part in the Bates–Morse Mountain book?

Don Dearborn and I are co-editors. Joe Hall, Mike Retelle, Bev Johnson, Brett Huggett, Dyk Eusden, Don, myself, and a few alums are all contributing chapters. There are three still to be written. Then we’ll meet at Shortridge to synthesize the climate understanding or awareness we’ve gotten from our individual observations and disciplines, so we can write a summary chapter that will make a strong statement about coastal climate adaptation.

Laura Sewall (center) and, to her left, former Bates–Morse Mountain director Judy Marden ’66, lead alumni and friends on a hike at the conservation area during Reunion 2019 in June. (Theophil Sylso/Bates College)

What attracted you to the Bates–Morse Mountain job?

Oh, boy, there is so much. One is the place itself, Morse Mountain. I live next door to it on what was my grandmother’s property, and in visiting her summer house from Arizona, I kept looking into the marsh and thinking, If only I could take care of the marsh with students. And so 10 years later, in 2008, my predecessor, Judy Marden ’66, said, “Laura, I’ve got a job for you.”

This was an opportunity like none I’d had for bringing a regional awareness to stewardship.

You’ve worked with Bates geologist Beverly Johnson and her students on measuring “blue carbon” — carbon stored in the marshes. It amounts to hundreds of tons each year.

I think the most important thing I’ve learned was how valuable the salt marshes are, including the degree of carbon storage.

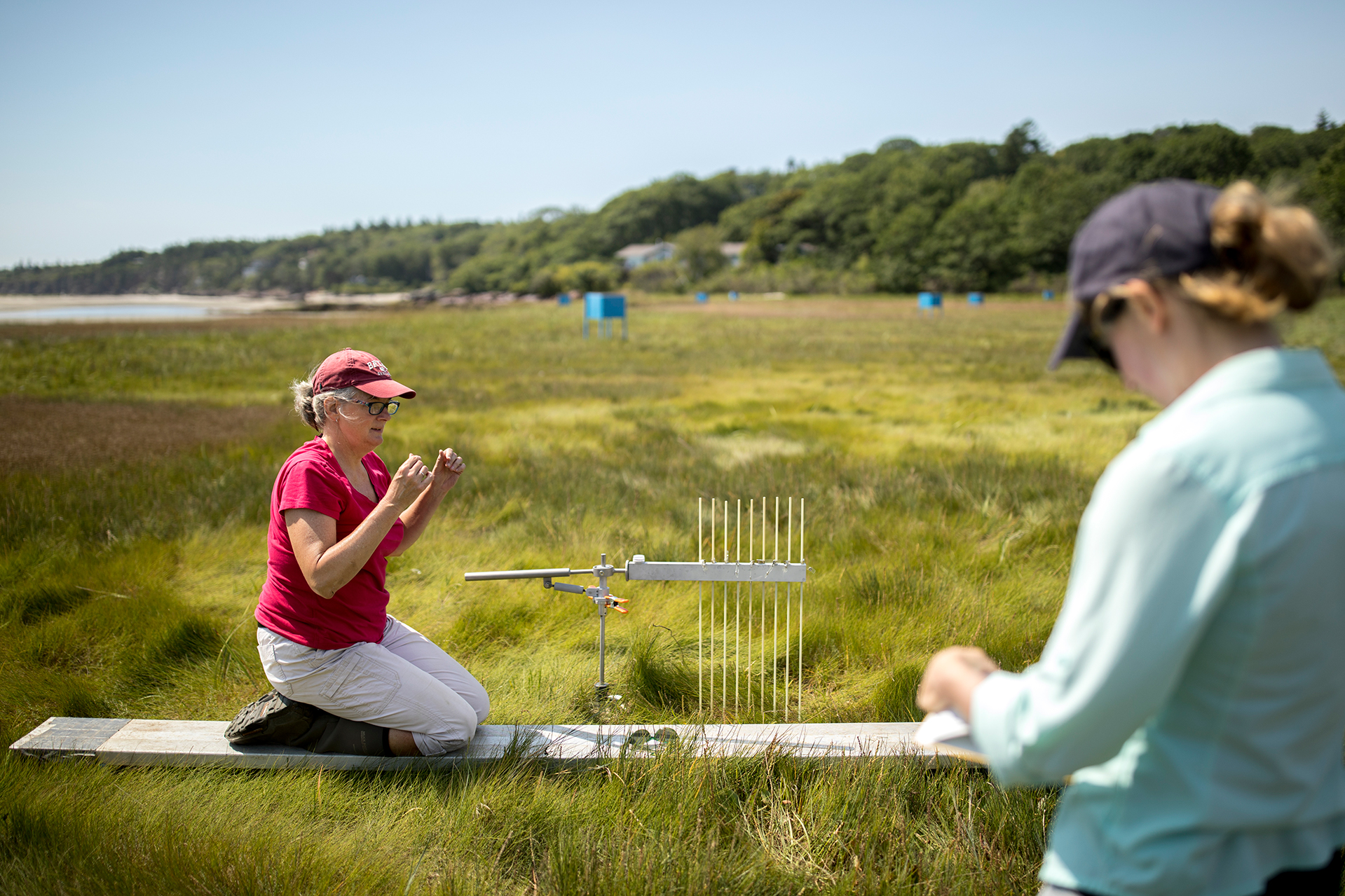

Professor of Geology Beverly Johnson uses a sediment elevation table to measure the height of the Sprague Marsh, part of the Bates–Morse Mountain Conservation Area, in August 2018. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Robert Costanza, an ecological economist who’s well-known for developing valuations for different ecosystem types, estimates that salt marshes are worth $194,000 per year per hectare because of ecosystem services, which include things like storm buffering, water filtration, fisheries support. That makes the Sprague Marsh, at 74 acres, worth $5.8 million per year. This doesn’t even include carbon storage.

You have a strong history of engaging Bates–Morse Mountain with initiatives or organizations that have similar interests.

In my first four or five years I attended a lot of meetings pertaining to coastal issues — professional conferences, and meetings with state agencies and environmental NGOs.

People saw that the director of the Bates–Morse Mountain Conservation Area was showing up, and so opportunities to engage in various projects opened up. And it made Bates more visible as a partner in environmental work in Maine.

This pitch pine dune woodland at Bates–Morse Mountain is a globally rare ecosystem and possesses a rare beauty, as well. (Laura Sewall/Bates College)

In fact, the Northeastern Coastal Stations Alliance was your brainchild — and one of the people who helped get it off the ground was your Bates–Morse Mountain successor, Caitlin Cleaver, who was then at the Hurricane Island Center.

That’s the partnership I’m probably most proud of. It’s a group of about a dozen stations, ranging from Shoals Marine Lab, on Appledore Island off Kittery, to the College of the Atlantic stations off Mount Desert.

It’s a loose, grassroots organization with a great mission. The idea is to collaborate on basic monitoring so that we can track changing conditions in the near-shore zone across the expanse of the Gulf of Maine.

What other accomplishments at Shortridge and Bates–Morse Mountain are you proud of?

The Shortridge Summer Residency for students has proven to be a solid use of the facility. They’ve done field research, and shared that work with the public and policy makers.

Seen in 2015, Professor of Geology Mike Retelle reviews time-lapse photography of beach erosion with Ian Hillenbrand ’17 and Nicole Cueli ’16 at the college’s Coastal Center at Shortridge, adjacent to Bates–Morse Mountain. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

They’ve done thesis work, been artists-in-residence, been interns for local land trusts. More than 60 students have done the residency since 2009. Shortridge has been busy overall — 560 Bates people used it during the last academic year.

Also, I’m really proud of the way the two gatekeepers, the caretaker, and I have coordinated our work and been a really good team.

How is rapid climate change affecting Bates–Morse Mountain?

It’s mostly about higher tides. So the causeway across Sprague Marsh floods more frequently than it used to — we now warn people that high tide may cover the causeway and they should expect to wait or wade.

There has also been quite a bit of erosion on the dune front along Seawall Beach — about 11 meters in the center of the beach since 1992. Mike Retelle has been tracking that. I’ve seen a lot of erosion up in the marsh.

The dune pitch pines are dying back. It would be hard to say without putting in wells to measure hydrology and salinity, but their root system is the closest to the seawater.

“People love Bates–Morse Mountain, and I think everyone who’s a stakeholder has felt Bates has taken good care of it.”

Some parts of the marsh are healthy and luxuriant, and in other areas you now see muddy patches among the vegetation — little hillocks of plant growth with mud around them. I’ve been told by a salt marsh researcher from the University of New Hampshire, David Burdick, that it’s an early sign of conversion to mudflats.

The Bates–Morse Mountain bylaws require us to let nature take its course. So we’re able to observe without interference — the hemlocks are slowly dying because of hemlock wooly adelgid, and we need to witness it.

Holding a hemlock branch infested with invasive and destructive hemlock woolly adelgids, Assistant Professor of Biology Brett Huggett observes hemlock trees during a Short Term 2015 field trip at Bates–Morse Mountain. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

I created a sign to educate visitors about the die-off. You walk up the mountain from the marsh and see a dying mess in the forest. It’s a visible sign of climate change, and it’s a teachable moment.

You’ve brought some of Beverly Johnson’s research techniques to the marsh near your own home — a sediment elevation table to measure changes in the level of the marsh surface, and a system for monitoring vegetation changes over time.

Bev and I installed the sediment elevation table right in front of my house in the Sprague Marsh, and I do a vegetation transect in that area every year. Both provide measures to help us predict the response of the marsh to sea level rise. We installed three additional SETs, along with vegetation transect sites, further up the marsh as well.

How has this job helped you make sense of your life?

I have always been purpose-driven. In my life, I chose every step along the way because I saw a more interesting purpose or a closer way to take care of some bit of the Earth.

Seen in December 2017, Isobel Curtis ’17 works on a project to establish forest survey plots at Bates–Morse Mountain. The project is part of a multi-group effort to monitor significant Maine ecosystems in the face of climate change. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

That’s what Bates–Morse Mountain has been — a great opportunity to take care of a place. This has given me the opportunity to satisfy that yearning.

It’s also been satisfying to feel that I’m of service to the community there. People love Bates–Morse Mountain, and I think everyone who’s a stakeholder has felt like Bates has taken good care of it during my tenure and Judy’s, too. That feels really good. A big part of that has been the opportunity to educate, too — both students and the public.

You have quite a family history in this region — your house is on property that once belonged to your great-great-grandparents. Did you know the conservation area well before you became director?

When I was teaching in Arizona, I would finish up in May and I’d come back here. In the early evenings, I’d ride my bike over the mountain, which was, of course, against the rules. I didn’t know that — I saw very few people and no one ever stopped me. I certainly knew Seawall Beach, and the Sprague Marsh from paddling into it, but that was about it.

One of two rivers within the Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area, the Morse River flows into the ocean near Popham Beach. (Brittney Lohmiller for Bates College)

Your great-great-grandmother, Emma Sewall, was one of Maine’s earliest female photographers. She photographed working people, including workers in the salt marshes.

My sister Abbie Sewall is also a photographer, and she took many of Emma’s glass plates and published them in a book, Message Through Time. Emma also wrote a little book, The Rivers and Marshes of Small Point, Maine. It’s funny to think that I’m simply following in her footsteps, like my sister — both of us carrying Emma’s work into this era.