It’s the day of Opening Convocation at Bates, Sept. 3, the official beginning of the 2019–20 academic year.

For professor Jane Costlow, the day marks the beginning of an ending. After 33 years at Bates, Costlow, the college’s Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies, has started her final year of teaching.

Costlow personifies a sea change in higher education and at Bates as baby-boomer professors retire from their institutions en masse. During the current decade, roughly a third of the Bates faculty will retire, leaving behind the life of the academy to which they’ve devoted much of their adult lives.

Costlow’s Final Year

Join us as we follow Jane Costlow — esteemed Bates teacher, scholar, and colleague — month by month during her 34th and final academic year.

When Costlow first arrived at Bates, in fall 1986, she joined the Russian department, teaching language and literature.

Jane Costlow arrives at her Hedge Hall office on Sept. 3, turning to smile at her next-door neighbor, Sonja Pieck, associate professor of environmental studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I remember a mild sense of panic,” she says, “because it was my first teaching job. I was really excited but I was also really kind of nervous.”

The excitement came from what she’d already learned about her new college during interviews. “I had wonderful interactions with people,” she says.

“I had a sense that students were down-to-earth. And I was meeting other faculty and I thought, ‘Wow, these are really cool people.'”

- Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College

- Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College

- Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College

Top left, Costlow and colleague Sonja Pieck trade notes about their summers. Top right, Costlow’s “Welcome back!!!” office-door message greets students. Above, Costlow throws on her academic gown before heading to Convocation. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

It’s time for Convocation, and with a casual ease Costlow dons her academic gown and a doctoral hood that she created herself. Its colors, black and “Yale blue,” signify her Yale degree in Slavic languages and literatures.

Adding a personal touch, she dons a straw hat that has been sitting atop a file cabinet since she wore it at Commencement last May.

Then she heads out.

After Convocation, Costlow takes a moment to catch up with friends Beverly Johnson, professor of geology, and Lynne Lewis, Elmer W. Campbell Professor of Economics. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Ever been on a treadmill at the gym when the speed suddenly goes up? That’s what a college campus feels like as summer turns to fall.

For any educator, “that’s a huge transition,” Costlow says of switching from summer mode, when professors can, distraction-free, dig deeply into their research, to the academic year and its multiple demands.

“You suddenly realize you’ll be in the classroom. You’ll have all these thesis students. In many ways, your time is not yours anymore,” she says. “But it’s always exciting to see your students, especially students returning from abroad.”

And it’s on Costlow’s mind that the rhythm of her life will change. “It’s just a little bit bittersweet to think, “Oh, well, this is the last time I’ll do this.”

After Convocation, Costlow prepares for the first session of her course “Lives in Place,” set for the next day, and awaits a senior environmental studies major en route to her office for an initial thesis meeting. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The day after Convocation is the first day of classes and Costlow’s first session for her course “Lives in Place.”

Presenting words and images of and by writers, filmmakers, and artists, the course examines the question “What does it mean to live sustainably in place?”

Proving that even a 33-year Bates veteran can make a mistake, Costlow makes a false step on the first day of her final year. Accustomed to teaching in a certain Hedge Hall classroom year after year, she arrives there only to see another Bates veteran, Dana Professor of Anthropology Loring Danforth, preparing for his class.

Checking her course schedule (for the first time, she abashedly admits), Costlow races across campus to the correct classroom, in Olin Arts Center.

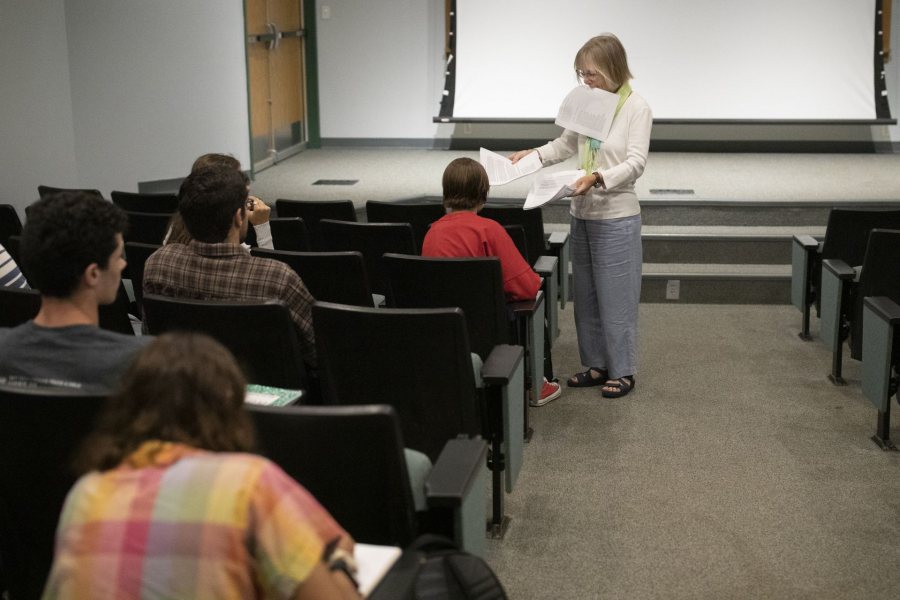

After a false start, Costlow arrives for her “Lives in Place” class in Olin Arts Center. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

On a day of last firsts, the location of the class offers something different: a full circle. In 1986, Costlow’s very first class was in Olin, then a brand-new building that hadn’t even been dedicated yet (it would happen that October).

Back in Olin again, Costlow introduces herself to the class and explains her career trajectory from the Russian department to the environmental studies program — a move inspired partly by her explorations of meaning and symbolism of Russian forests. Then she hands out the course syllabus.

The document opens with a drawing of Mount Katahdin by the American Modernist Marsden Hartley (whose artwork is a notable part of the Bates Museum of Art collection) and includes a quote from Aldo Leopold: “We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in.”

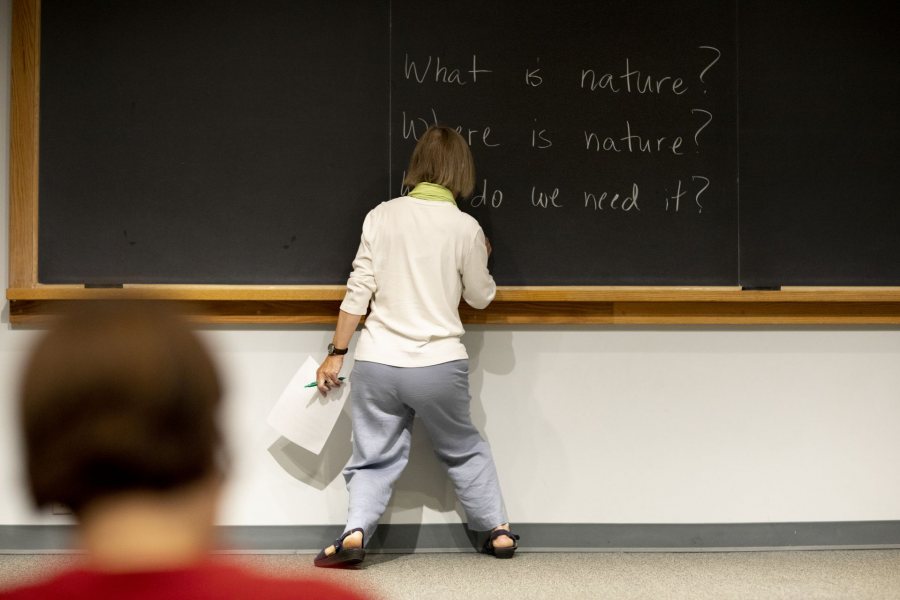

At top, Costlow distributes the syllabus for her course “Lives in Place.” Above left, she crouches to write the last of four opening-day prompts. Above right, she speaks to the class. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

After writing a few initial but essential questions on the blackboard, Costlow asks her students to break into small groups and discuss the questions:

What is nature? Where is nature? Why do we need it? What kinds of nature do we need?

Like many courses taught by longtime professors, “Lives in Place” has a durable framework that Costlow leans on year after year. On the other hand, “I always mix it up a little bit,” she says.

During the semester, her students will consider how “place comes to mean something important to people in different cultures and different places, and how people can be displaced from where they feel connected.”

Displacement has “long been a central and tragic aspect of modern human lives,” she adds. “And it seems to be becoming increasingly pressing as an issue.”

Jane Costlow shares her thoughts as the new academic year approaches. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

After class, Costlow heads back to her Hedge Hall office for a late-morning appointment with Jesse Saffeir ’20, an environmental studies major from Pownal, Maine.

Costlow reacts after Jesse Saffeir ’20 gives her a book of original poetry inspired by her Otis Fellowship experience in Maine. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Saffeir has returned to Bates after time away in different places: a winter semester in Iceland, followed by an Otis Fellowship from Bates over the summer, which she used to travel, experience, and consider the swaths of Maine land cleared for overhead electrical transmission towers.

A tangible result of her Otis Fellowship is a book of original poetry. She gives a copy to Costlow, who accepts it with warmth and joy, as Saffeir bows her head in appreciation.