One hundred and one years ago, the build-up to the annual Bates-Bowdoin football game had disputes and divided loyalties — classic trappings of a historic rivalry.

And, for Bates fans, the 1898 game delivered what a rivalry game should, a victory and a hero, William Allen Saunders, the unlikely scorer of the game’s only touchdown.

Yet in 1898, the grid rivalry, now one of the nation’s longest-running, was just seven years old. And, at least from Bates’ perspective, the rivalry had gotten off to a slow start, with Bowdoin easily winning the first five editions by a combined score of 186 to 6.

Bates-Bowdoin Football, No. 122

The 2019 Bates-Bowdoin football game, No. 122 in the historic rivalry, is now history: See highlights from the Bobcats’ 30-5 victory at Garcelon Field on Nov. 2.

At the time, interest in college football was surging both nationally and in Maine. With questions of masculinity at the fore in late 19th-century society, the country’s college football fields — offering a far more violent version of the game than today’s — became popular proving grounds for the modern man.

Newspapers played up the game’s war-like violence. One pre-game headline in the Lewiston Evening Journal of the era proclaimed, “Bowdoin and Bates arrayed in the panoply of war at Brunswick.”

For the 1897 game, a year before Saunders’ star turn, Bates supporters filled the trolley for the 90-minute trip to Brunswick. At the station, the Bates contingent let loose their traditional cheer: “Boomalaka, boomalaka, Bates — boom, boom!”

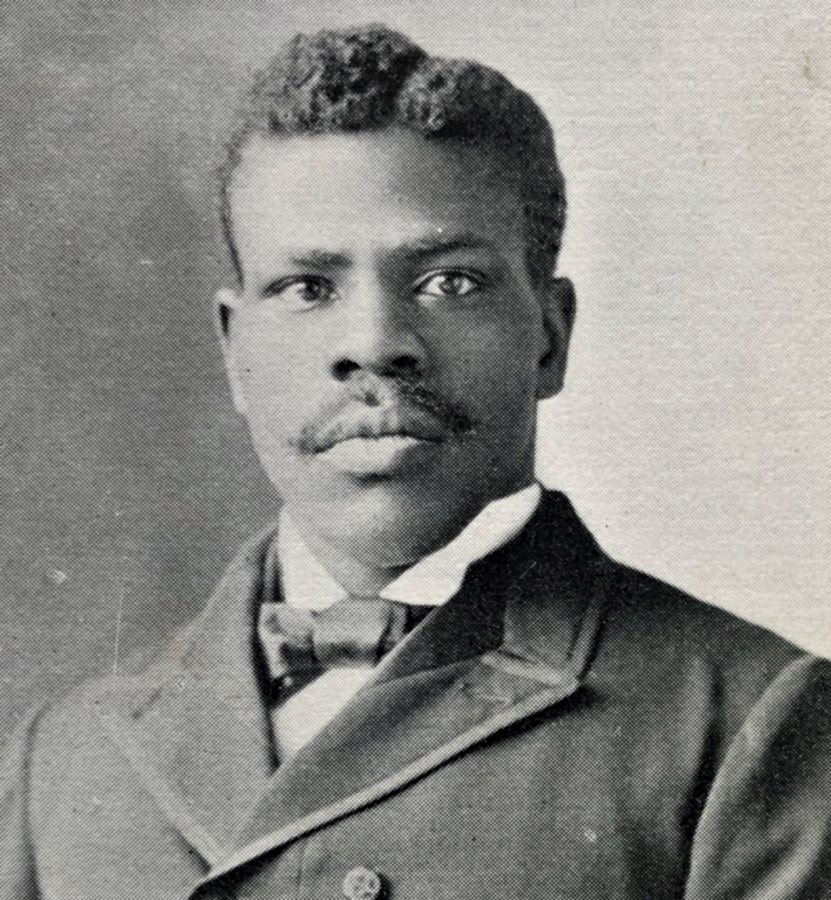

The Mirror yearbook photo of William Allen Saunders, Class of 1899, the hero of the Bates-Bowdoin game of 1898. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

And boom, like that, Bates won the game, securing its first title in the nascent Maine State Series competition, later to become the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin series when the University of Maine left the group in 1964.

Perhaps smarting from its first setback in the budding rivalry, Bowdoin in 1898 played hardball. Pointing to its “ability to draw a big crowd,” according to a Journal story two days before the Oct. 29 game, Bowdoin demanded a bigger share of the gate receipts before agreeing to travel to Lewiston.

“The people are coming, coming from everywhere.”

When the two schools reached a revenue agreement a day later, the Journal headline declared, “Foot Ball Peace Assured.” With the game on, the hype machine was on, 19th-century style.

“Everyone who knows the difference between a football and an egg will be on the grounds,” said the Journal, noting that anticipation for the game in Maine has “resembled the feeling throughout New England over the Yale-Harvard games.”

Yes, the paper said, “the people are coming, coming from everywhere.”

And they did, a throng of 2,500 attending the game on a foggy, drizzly day at Lee Park (Garcelon Field wouldn’t be completed for another year). A bygone city commons once located at the intersection of Sabattus Street and East Avenue, Lee Park was known mostly for hosting traveling circuses. It became a housing development in the early 1900s.

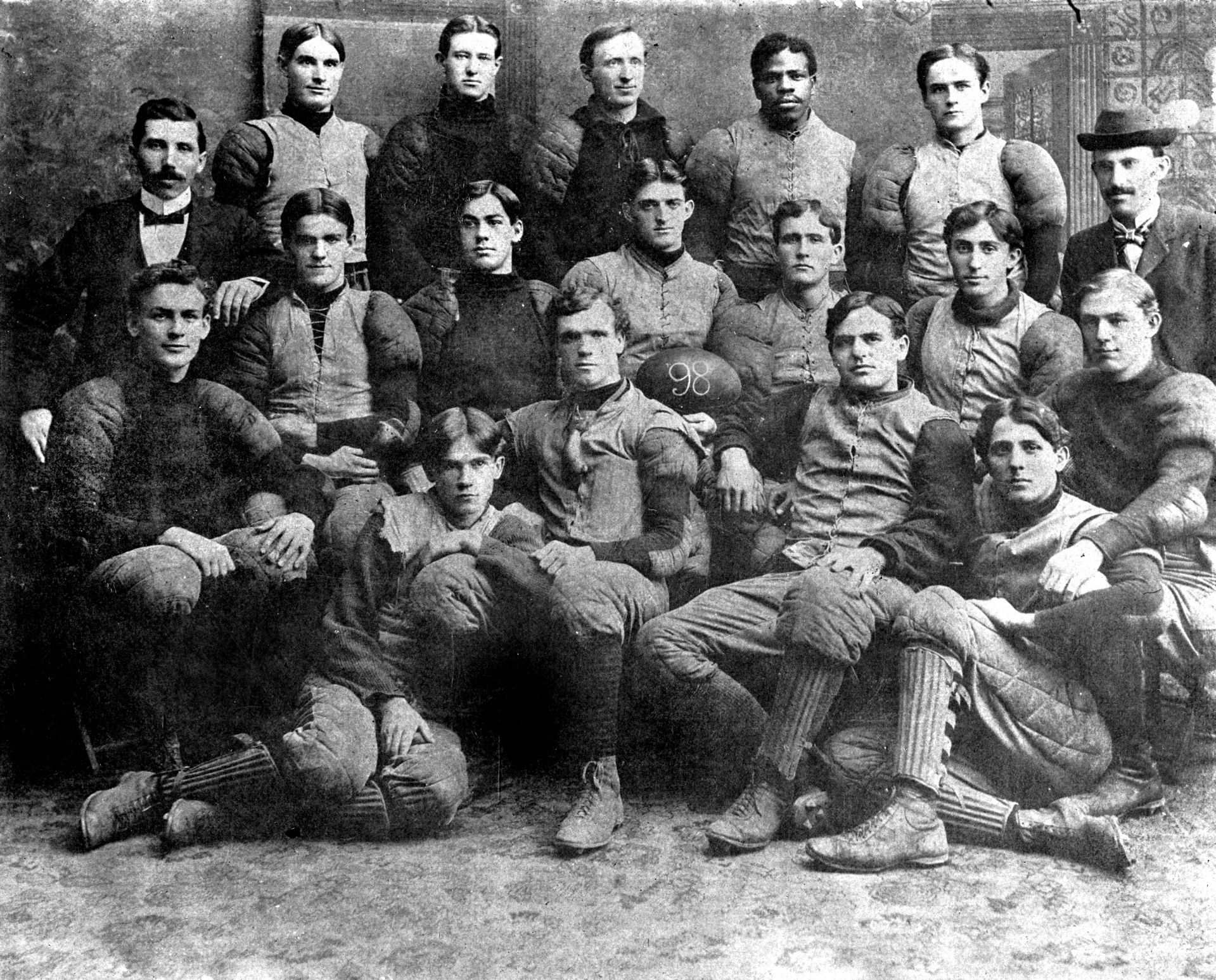

The undefeated 6-0 Bates football team of 1898 poses for a team photo. William Saunders, scorer of the winning touchdown vs. Bowdoin that year, is standing third from right. Team captain Nate Pulsifer, who made a key block on the winning play, is seated at center. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Bowdoin, considered the bigger and more physical of the two teams, entered the game with a 5-2 record, its only losses being to Ivy League powers Dartmouth and Harvard. Hardscrabble Bates, often called “the farmers” in media accounts, was 4-0, having beaten New Hampshire State College, the University of Maine (twice), and Phillips Exeter Academy.

(Winless Colby, meanwhile, wasn’t part of that year’s Colby-Bates-Bowdoin talk; its football team needed more “firmness in muscle before they can hope to cope successfully with Bates or Bowdoin,” noted the Journal.)

“A few of the young women…bolted outright from the Bates standard and bravely shook the black and white of the other side.”

You know a sports rivalry has arrived when it moves outside the sports media, and that’s what happened in 1898. On game day, the late edition of the Journal devoted its “Social World” column to the Bates-Bowdoin game, noting that “the young people were at Lee Park this afternoon.”

More than football — something tribal — was at stake, the column suggested.

“The raw October air brought the Bates color into the cheeks of the lassies,” the paper said, “but ’twas hard for some of them to be loyal to the garnet and white. A few of the young women…bolted outright from the Bates standard and bravely shook the black and white of the other side.” Ouch!

The 1898 game, a 6-0 victory for Bates, was “a nerve destroyer,” the Journal reported. The teams moved the ball, but had trouble scoring; the action drove the throng into a tizzy, and “police were unable to keep the crowd from swarming over the field at times,” reported the Bowdoin Orient student newspaper.

Midway through the first half, Bates’ William Allen Saunders, a senior from the South, ran for the game’s only touchdown.

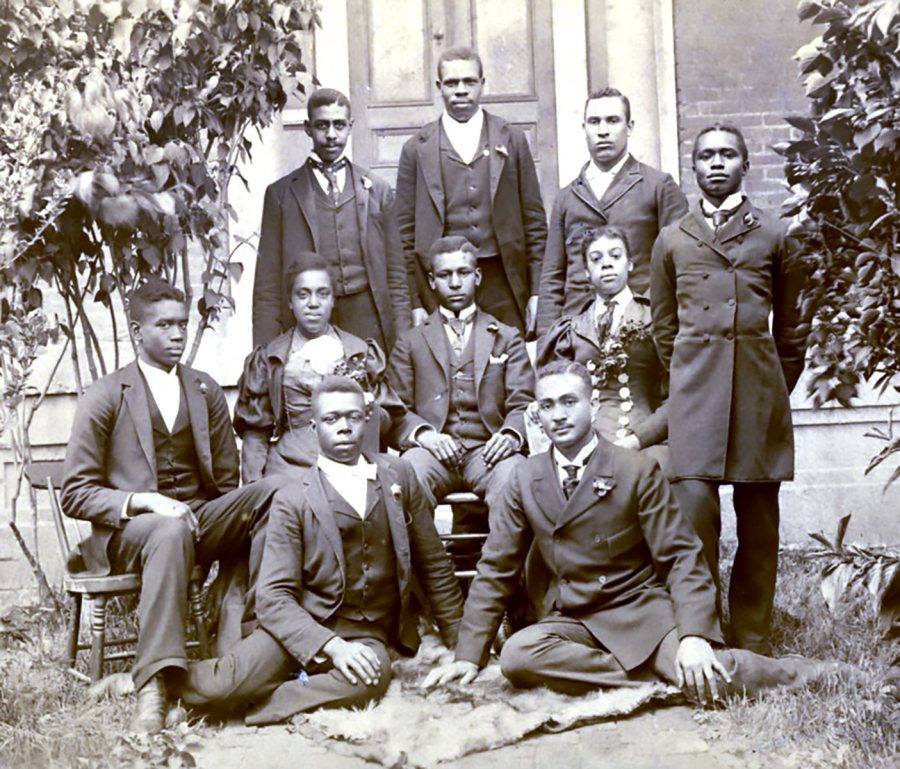

Born in Louisa Court House, Va., Saunders came to Bates after attending Storer School, later Storer College, in Harpers Ferry, W.Va., a historically black institution founded just after the Civil War with the help of Bates founder Oren Cheney. (Stella James also studied at Storer before she became the first African American woman to graduate from Bates, in 1897.)

Before matriculating at Bates, William Saunders (standing, second from left) attended Storer School, graduating with his fellow students in 1895. (Storer College Digital Photographs Collection / West Virginia and Regional History Center)

Besides football, Saunders competed in track and field at Bates, in the hammer and shot put. He also served as librarian of one of the literary societies, Eurosophia.

Following graduation, Saunders taught public school in Coaldale, W.Va., and served as a grade-school principal in Hagerstown, Md., before joining the faculty at Bluefield Colored Institute, now Bluefield State College.

He joined the faculty of Storer College in 1907, teaching math, natural sciences, religion, and Latin. He married Inez Johnson and they built a home near the Storer campus, which today is a bed and breakfast.

Saunders retired from Storer in 1951, and his date of death is unknown. A Bates oral history tells the story of a classmate, George Parsons, who visited Saunders in the 1950s, when both were in their 80s. Parsons wanted to take Saunders to dinner but Saunders demurred — no white restaurant in town would serve a black man.

Shortly after joining the faculty of Storer College, William Saunders (second from right, with clarinet) poses with the Storer College Cornet Band in 1908. (Storer College Digital Photographs Collection / West Virginia and Regional History Center)

While Saunders was the hero of the 1898 game, by today’s rules he would never have been a ball carrier. He was an offensive guard — a blocking position today.

Back then, the rules required only five players to be on the line of scrimmage at the start of a play, compared to seven today. That allowed more players to line up in the backfield. And that led to battering-ram formations, including the flying wedge, in which a big lineman, in this case Saunders, and several blockers would line up in the backfield and get a running start into the defense.

Known as a “guard-back” or “tackle-back” formation, it’s what made Saunders the hero of the Bates-Bowdoin game of 1898.

Indeed, football in the 1890s hardly resembled today’s game. With the forward pass still a few years away, the game was all about the ball carrier and his blockers bashing into the defense, time and again. In Bates-Bowdoin terms, the Journal described the “slap of canvas against canvas” as two sides crashed together.

“Time and again the giant guard, Saunders, went into the line and always for a gain,” said the Student. “Saunders played like a fiend,” reported the Journal. “It always took two men to bring him down.” (Though not big by today’s standards, Saunders, at 5-foot-10 and 173 pounds, was among the tallest and heaviest Bates players.)

This commemorative paperweight depicts William Saunders’ gate-winning touchdown vs. Bowdoin on Oct. 29, 1898. It was given to Bates by Bowdoin graduate Bruce MacDonald, grandson of Nate Pulsifer, captain of the 1898 football team and Saunders’ classmate who made a key block on the winning play. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Bates’ game-winning, 14-minute touchdown drive started at midfield. With a “steady humming between tackles and guards,” Bates advanced to the Bowdoin 20. The Bates captain, senior running back Nate Pulsifer, carried to the 10 for a first down.

Then came Saunders’ turn. He carried to the Bowdoin 4, and then, with Pulsifer and sophomore running back Frank Halliday leading the way, Saunders “went over the line for the first and only touchdown of the game.” (A commemorative paperweight, given to Bates by Pulsifer’s grandson, depicts the winning play and the huge crowd at Lee Park.)

The rest of the game, reported the Student, “abounded in runs, fumbles, plunges that seemed to be back-breakers, punts, and hard tackles” — but no more scoring. Bates’ defense held; it would allow just 11 points in its six wins in 1898.

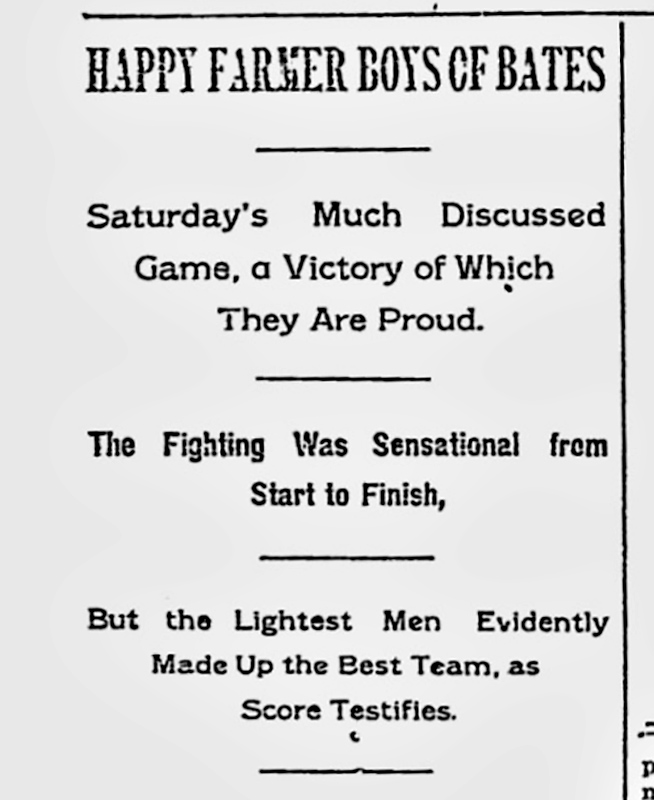

Two days after the Bates victory, headlines in the Lewiston Evening Journal on Oct. 31, 1898, gave kudos to the “happy farmer boys of Bates.”

The Bates victory was “universally admitted to be the greatest contest ever held between Maine colleges,” stated the Student.

The Journal agreed, saying the game was “the fiercest foot ball ever seen in this state” with a deserving winner: a “light, stocky, well-trained team that was playing a game of foot ball only excelled by the crack teams of the country.”

The victory kicked off a night of celebration at Bates, including boisterous rides around town on the local trolley. Known as the Figure Eight for the shape of its route around Lewiston and Auburn, it “was traveled with a liberal amount of fireworks and red fire on each car,” reported the Journal.

And there were victory songs aplenty, at Bowdoin’s expense, including a new one sung to the tune of “Marching Through Georgia,” with this verse:

The farmer boys at Bates have learned

The way to plough the ground,

As the headless birds at Bowdoin,

To their sorrow now have found.

Then with cheers and shouts of triumph

Let the atmosphere resound,

While the Bowdoin dudes are marching back to Brunswick.