In the early 1990s, Bates professor Thomas Wenzel began to think that the traditional approach to teaching chemistry — lectures and what he calls “recipe-based” laboratory assignments — was missing something.

For instance, students that Wenzel expected to thrive in his courses scored poorly on exams. Yet, in contrast, the students he hired to perform hands-on research in his Bates lab were highly engaged with the material.

“It seemed that the learning that happened in the research work was so much deeper and so much longer-lasting,” Wenzel says. “I realized I needed to make my instructional laboratories more research-like in their approach.”

So in his courses, Wenzel started putting students in groups to puzzle through questions and calculations. He framed his lab assignments as solving problems instead of following recipes. His students engaged more robustly with the material, and exam scores went up.

Dana Professor of Chemistry Tom Wenzel, who will retire in 2020, has been honored with the establishment of a student research fund in his name and an achievement award from the American Chemical Society. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Those simple steps began a pedagogical evolution that has made Wenzel, now the college’s Dana Professor of Chemistry, a national leader in the teaching of chemistry — including pioneering work to create open-access course materials — as well as a model for involving students in research and a prolific researcher.

And at the start of his last year of teaching before retirement from Bates in 2020, Wenzel received two major honors that recognize his contributions to his field and to the lives of his students.

“It’s hard to imagine a more gratifying way to end my career.”

In August, the American Chemical Society awarded him its 2019 George C. Pimentel Award for “outstanding contributions to chemical education.”

Soon thereafter, one of Wenzel’s former students paid tribute to his mentor by establishing the Thomas J. Wenzel Endowed Fund for Undergraduate Chemistry Research, to support students conducting summer research on campus.

“It’s hard to imagine a more gratifying way to end my career,” Wenzel says of the two career honors.

+A Few Wenzel Awards

Since joining the Bates faculty in 1981, Tom Wenzel has produced 181 scholarly publications: 96 on research activities (refereed); 35 on educational activities (refereed); and 50 others, many of which have to do with efforts to promote undergraduate research. His external grants for research and education total more than $3.75 million.

Wenzel’s honors have included:

- 2020: American Chemical Society National Award, the George C. Pimentel Award in Chemical Education

- 2016: American Chemical Society Fellow

- 2010: American Chemical Society National Award for Research at an Undergraduate Institution

- 2003–05 and 1990–91: Camille and Henry Dreyfus Scholar

- 2002: Council on Undergraduate Research Fellows Award (the first chemist so recognized)

- 1999: J. Calvin Giddings Excellence in Education Award from the Analytical Division of the American Chemical Society

- 1997: Carnegie Foundation College Professor of the Year for the state of Maine

Rachel Austin, who taught at Bates from 1995 to 2015, saw firsthand how Wenzel transformed chemistry education.

“Tom has expanded the notion of ‘learning through doing’ to the teaching of chemistry at all levels of the undergraduate curriculum,” says Austin, who is the Diana T. and P. Roy Vagelos Professor of Chemistry at Barnard College and who nominated Wenzel for the Pimentel award.

She adds, “He was well ahead of the wide-scale recognition of the value of inquiry-based learning” in chemistry.

In this summer 2005 image of Tom Wenzel’s typically active research lab, Wenzel (left) and post-graduate research fellow Catherine Dignam (second from left) work with student researchers: from left, Matt Chodomel ’06, Shawna-Kaye Lester ’08, and Monique Brown ’07. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Complementing Wenzel’s accomplishments in chemistry education are his research achievements. He has published extensively on chirality, a molecular phenomenon that parallels “handedness” in humans.

He develops techniques to identify molecules that are mirror images of each other but can have different reactive effects — for example, one form of the drug thalidomide reduces morning sickness, but its mirror image was responsible for birth defects in the 1950s and 60s.

Along the way, Wenzel has become a pioneer in bringing undergraduates into his research lab. Some 128 students — 80 of them women — have worked in his lab since he joined the Bates faculty. Throughout his career, Austin says, Wenzel has been “an active proponent for the involvement of women and minorities in science.”

“One of my approaches was to start hiring first-year students out of my general chemistry core course into my research laboratory,” he says, “as a way to provide them a more realistic experience of what it meant to actually do chemistry.”

In addition to his publications on pedagogy, Wenzel has published some 40 articles on undergraduate research, been involved with the national Council on Undergraduate Research, and, in 2010, won the American Chemical Society Research at an Undergraduate Institution Award.

A nationally recognized advocate for undergraduate research, Tom Wenzel (third from right) poses with some of his students in 2015 at the International Chirality Conference. Wenzel chaired the 2015 event, the premier conference in his research field, and Bates was the only undergrad school represented. Back row, from left, William Patton ’15, Mira Carey-Hatch ’14, Yolanda Rodriguez ’15, Tom Wenzel, Alison Dowey ’15. Front row, from left, Tayla Duarte ’17, Cira Mollings Puentes ’16, Caroline Holme ’16, Brielle Dalvano ’16, and Anna Berenson ’16.

Of Wenzel’s 96 published research articles, 67 have had Bates student co-authors. One of those authors was Jim Weissman ’84, who says he always wanted to study chemistry, but his sophomore classes were a “rocky road.”

Wenzel both encouraged Weissman to stick with the major and helped him as he caught up with course work. Then he hired Weissman to work in his lab.

Wenzel “touched the lives of a lot of chemistry majors.”

For his senior thesis, Weissman studied methods for detecting pharmaceuticals and pollutants and, along with Wenzel and three fellow students, co-authored an article, “Lanthanide ions as luminescent chromophores for liquid chromatographic detection.”

Wenzel “had a unique style, and he touched the lives of a lot of chemistry majors,” Weissman says. “Had he not been at Bates, those opportunities that I had would not have been realized.”

That influence is sharply evident in the paper that Weissman coauthored. His fellow authors, Elsie DiBella ’85, Maureen J. Joseph ’83, and Joshua R. Schultz ’83, all earned doctoral degrees. They’ve all forged careers in biotech, as has Weissman, who is now chief operating officer at Dicerna Pharmaceuticals.

Early in this semester, Weissman and his wife, Kyoko Oba Weissman, donated $100,000 to Bates to establish the Thomas J. Wenzel Endowed Fund for Undergraduate Chemistry Research, which provides scholarships for students to conduct summer chemistry or biochemistry research on campus.

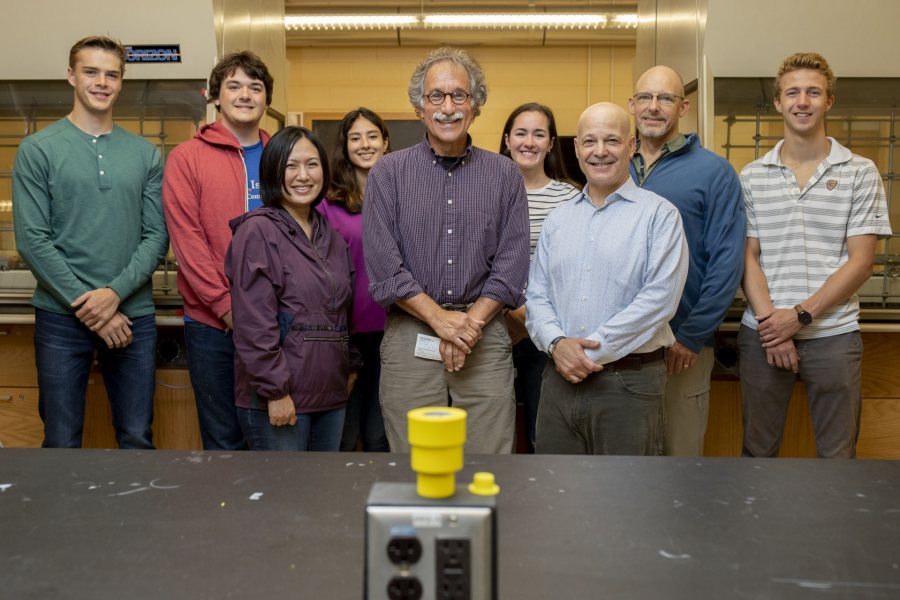

Tom Wenzel (center) is flanked by donors Jim Weissman ’84 and Kyoko Weissman as they celebrate the establishment in September of the Thomas J. Wenzel Endowed Fund for Undergraduate Chemistry Research. Joining them in Dana Chemistry Hall are, from left, Jake O’Hara ’21, Nick Jones ’20, Shanzeh Rauf ’21, Maddie Murphy ’20, Associate Professor of Chemistry Matt Côté, and Owen Bailey ’22. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In September, Wenzel and the Weissmans, who were on campus bringing their son back to Bates for his sophomore year, hand-delivered a $100,000 check to fund the endowment and gathered with chemistry students to celebrate the fund’s establishment.

“If I could only highlight one thing about my whole career, it would be engaging undergraduates in meaningful research,” Wenzel says.

“That a former student of mine gave money to the college to provide summer support for future undergraduates — forever — I truly don’t think there could be any more meaningful honor to me than that.”

Thomas Wenzel and Jim Weissman ’84 reconnect in a laboratory in Dana Chemistry Hall in September. Weissman, a chemistry major who was mentored by Wenzel and is now chief operating officer at Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, established with his wife an endowed fund in Wenzel’s name. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)