Professor of Psychology Krista Aronson is a key figure in the creation of the Diverse BookFinder, a Bates resource that tracks how diversity is represented in thousands of children’s picture books.

She’s also the mother of two daughters. One daughter is in preschool. A teacher there recently told Aronson, “I actually knew you before I knew you” — and the connection was the Diverse BookFinder.

In Ohio, where the preschool teacher had lived previously, her son’s middle school had based a classroom project on the DBF, and even used a beta version of its Collection Analysis Tool to audit the children’s book holdings in the school library. “I was flattered and excited,” says Aronson. “And I love to hear new ideas and new spins on our work.”

The episode illustrates the success attained by the DBF, a resource that identifies what groups — among Black and Indigenous People and People of Color, as the DBF mission statement says — are represented in a given book and, importantly, what messages the book conveys about those groups.

The episode illustrates the success attained by the DBF, a resource that identifies what groups — among Black and Indigenous People and People of Color, as the DBF mission statement says — are represented in a given book and, importantly, what messages the book conveys about those groups.

Since its launch in 2017, the DBF has broadened the reading choices for countless children and parents, thanks to its powerful Search Tool for multicultural picture books. It has also helped nearly 200 libraries analyze their picture book collections, enlarged its own collection from 2,000 to 3,000 books, established a newsletter and social media channels, and made national headlines.

“We have thousands of people who on a regular basis pay attention to the work that we’re doing, which is really wonderful,” Aronson says.

The DBF website, which was redesigned a year ago, makes clear the accessibility of the resource for parents of young children, librarians, researchers, and folks in publishing. And new developments this fall promise to further the reach of the DBF and its goal of giving a richer view of diversity to the youngest readers.

In December, after months of pilot testing, the DBF will officially unveil its Collection Analysis Tool. Essentially, the CAT makes publicly accessible the engine that has powered the BookFinder right along: an analytical method that uses book-specific data, meticulously compiled from the DBF’s books by Aronson’s team, to assess how any children’s book collection represents different groups.

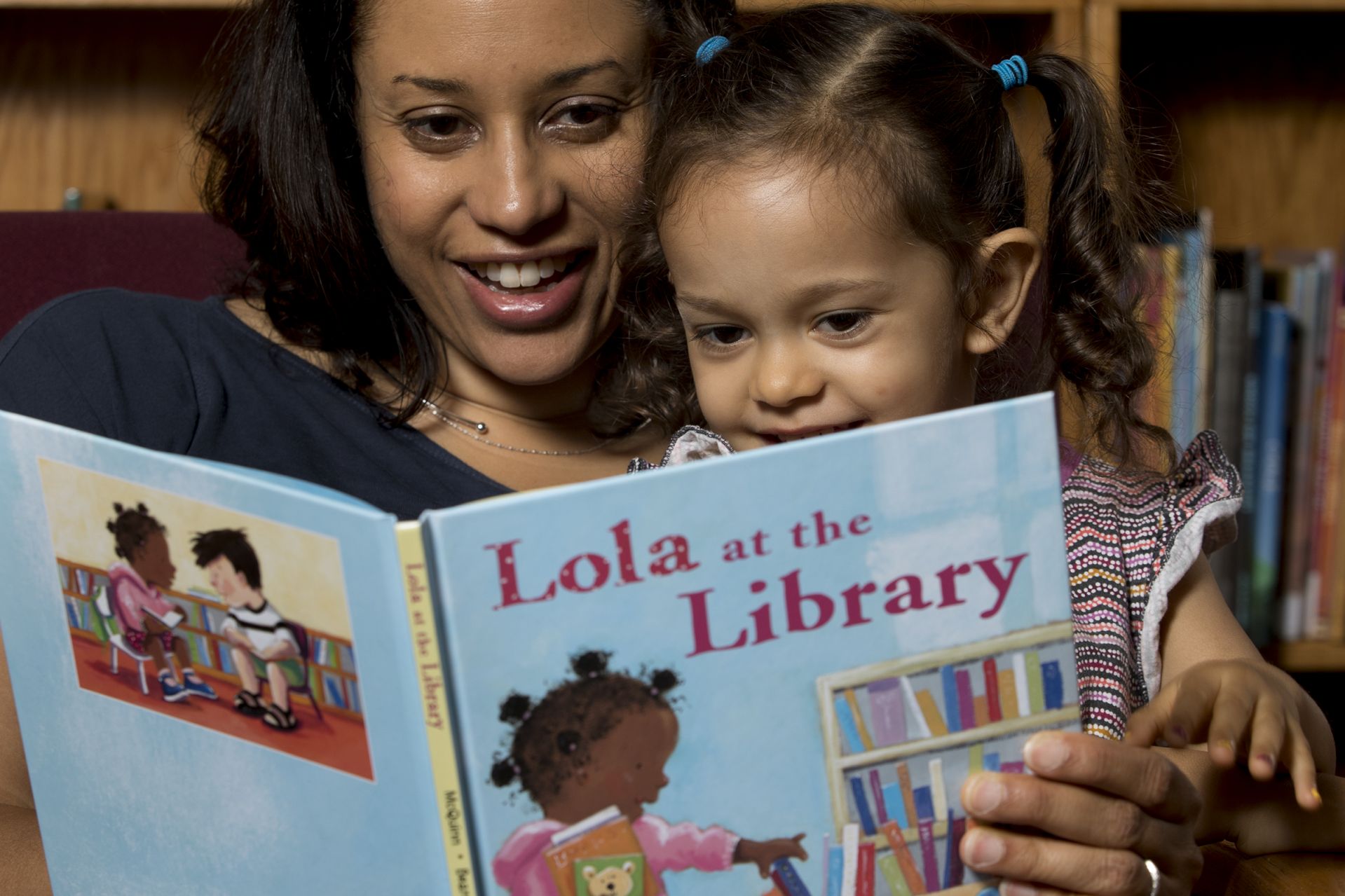

Professor of Psychology Krista Aronson reads in Ladd Library with her daughter Hope in 2017. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Moreover, the Diverse BookFinder team recently launched a program to help Maine libraries use the CAT to assess their children’s book collections for diversity — and, through a competitive grant process, provide successful applicants with $300 grants to buy books that will help balance those collections.

That effort has been made possible through a partnership with the Maine Humanities Council and a $50,000 grant from the Brooks Family Foundation of Portland, Maine. The grants will target underresourced libraries, as determined by number of librarians or collection budget relative to community size. (Mayo Street Arts, in Portland, and Lewiston’s Literacy Volunteers–Androscoggin will share $1,000 of the Brooks Family funds for development of their children’s libraries.)

Applying for the grant is a fairly straightforward process, says Aronson. First, a library needs to use the CAT, accessible via the DBF homepage, to analyze their picture book collection. (Creating an uploadable list of relevant ISBNs, or standardized book IDs, is the only tricky bit, she says, but there are tutorials online.)

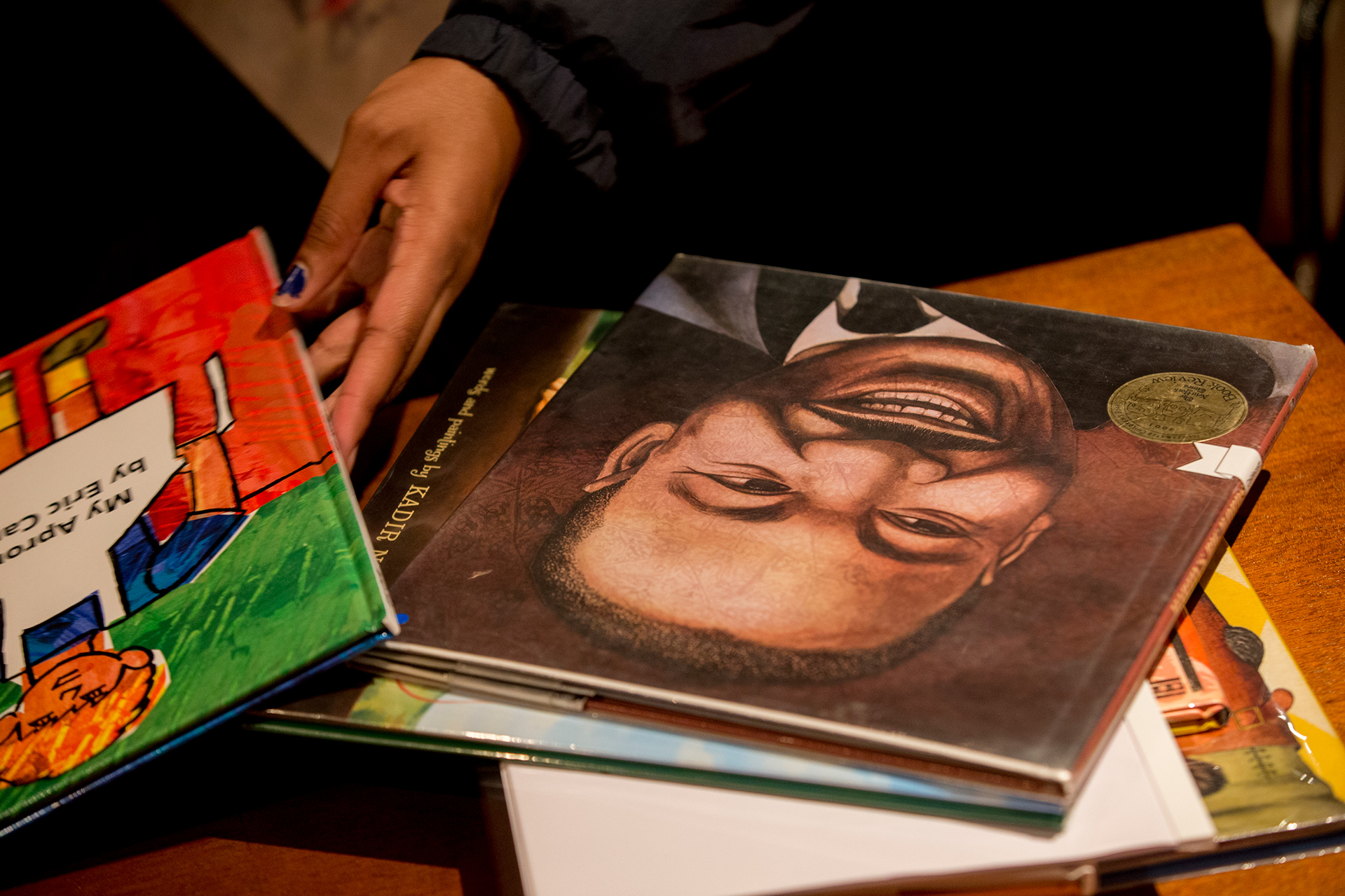

A selection of picture books at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Mass. Bates photographer Phyllis Graber Jensen took the photo during a Short Term 2017 visit to the museum by Krista Aronson and her students in a course related to the Diverse BookFinder. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“Within minutes, you’ll have your report,” she says. Then, to apply for the $300 grant, “you write 300 words or less about what you learned from your CAT report, and upload that and a list of books that you want to purchase.”

With the humanities council administering the application process, the program is accepting the first round of grant proposals now, with a Dec. 2 deadline. A second application period will begin during the winter.

“I hope that we can use the model that we’re creating with these funds to do something on the national level with additional support,” Aronson says. It’s one thing to raise consciousness and help librarians better understand their holdings, she explains, but ultimately there’s no better way to diversify a collection of children’s books than to help buy books.

To date, between beta testing and a soft launch earlier in the fall, about 195 libraries have used the CAT. The DBF team will start promoting the tool in December.

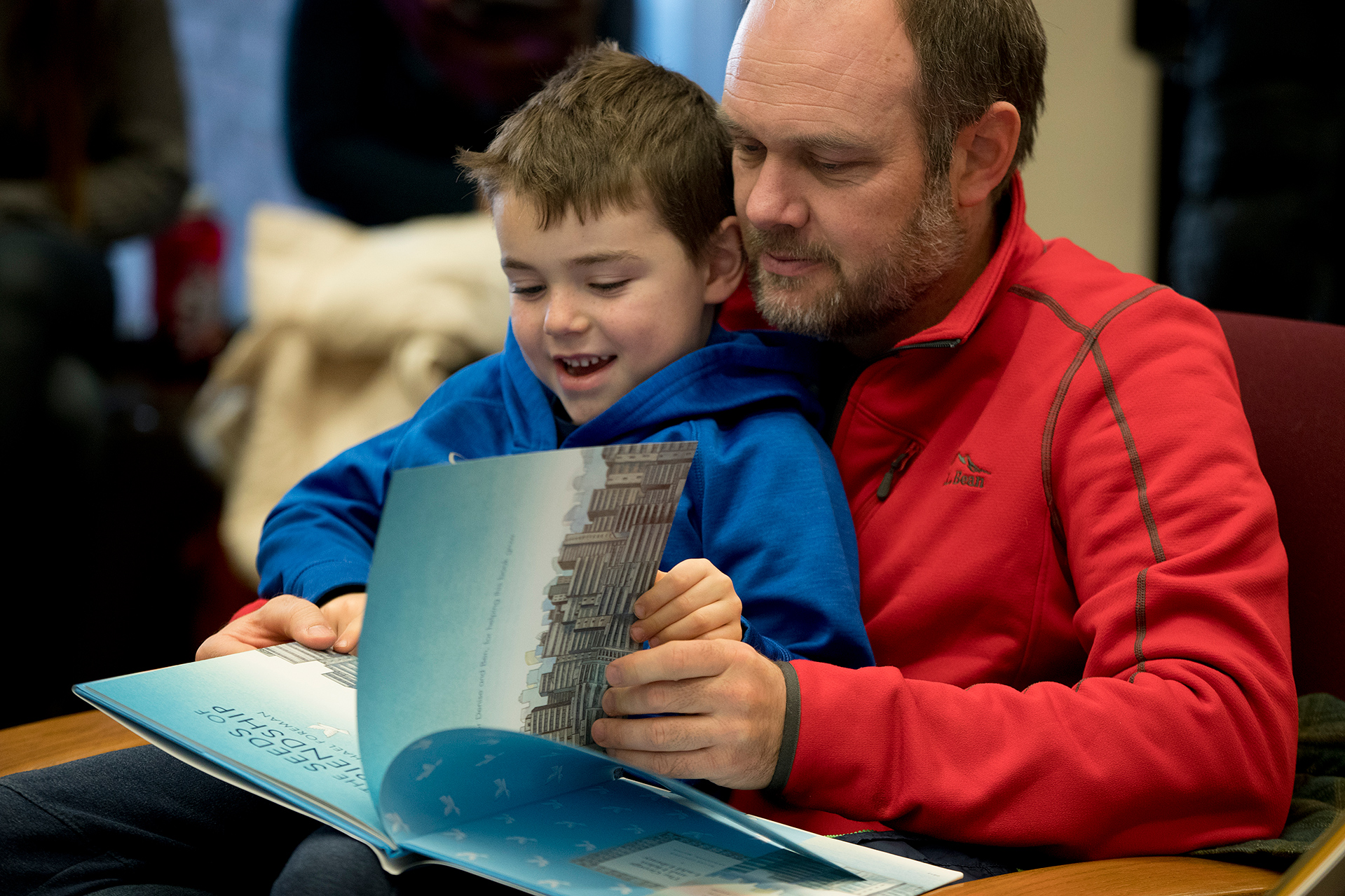

Matt Schlobohm ’00 reads a book with his son Avery, 6, in Ladd Library during a 2018 MLK Day workshop titled “Friends Across Difference.” The workshop used artmaking and picture books to explore cross-cultural relationship-building. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

One of the 195 is the Kennebunk Free Library in Kennebunk, Maine, which pilot-tested the CAT last spring. “It is so meaningful to see, with concrete numbers and graphs, how our collection represents all children,” says children’s librarian Maria Richardson. “It’s enabled me to develop our collection more mindfully.”

Among other results, the report prompted the library to expand its assortment of books about First/Native Nations/American Indian/Indigenous peoples, which had been underrepresented in its collection.

In fact, while the DBF is impressively inclusive in the attributes it measures, two sets are central to its workings. First, there are seven demographic categories (First/Native Nations being one of them). Then there are nine story types, which provide a lens for understanding what messages are conveyed about different demographic groups. Richardson, for one, has found the story types “extremely valuable,” she says. “I’ve started to use them when identifying books for purchase.”

Parents, like librarians, seeking diverse picture books find a robust helper in the DBF. Thanks to wide-ranging filters in the online Search Tool, you can tailor your search closely to your family’s circumstances. For instance, if you seek a book in the Folklore story type and the Asians/Pacific Islanders/Asian Americans demographic type — and you select Buddhism from the Religion category, too — the DBF will show you seven books. And even give you more information about each.

The Diverse BookFinder’s physical collection at Ladd Library in 2017. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

DBF project coordinator Andrea Breau is encouraged by the amount and kind of feedback she’s getting about the DBF from parents, via social media and directly from folks who sign out DBF books at Ladd. “We’ve heard from parents who have prepared for the arrival of a new baby by ‘registering’ for books they’ve found using our Search Tool’s filter functions to home in on their family’s own racial, cultural, and religious identifications,” she says.

“We’ve heard from those who follow our newsletter and blog posts to learn how they might use a picture book to discuss issues of race and racism that their children are currently facing at school. And, of course, there are those who follow us on social media to get book ideas when their creativity is running low or to keep up with what’s happening in the broader diverse books movement.”

Aronson points out that as soon as new books are added to the collection in Ladd Library, the DBF team (this year including sophomores Ojochenemi Maji and Isabella David)‚ codes them for the database. The website reflects this constant updating in a feature called Live Data Charts, which “are a first in the field,” Aronson points out. “And Bates is a part of it.”

For Aronson, the accessibility of the DBF data beyond academe satisfies another deeply felt goal. “It represents the translation of research-based academic data into something that’s useful and usable for the public. When you think about how we engage and share out with people, how we move out of strictly academic spaces and interact with people, that’s certainly a good way to do it,” she says.

“It’s really exciting.”