For children and their caregivers, there’s a session with books and activities designed to engage our youngest citizens with the topic of race and racism.

In a career-preparation presentation, Bates alumni will discuss how their identities — as defined by gender, race, sexual orientation, faith, and so on — have informed their choices of industry, organization, geography, and professional activities.

A visiting scholar will describe his campus’s reaction, including a book burning, to a visit by a Latinx author.

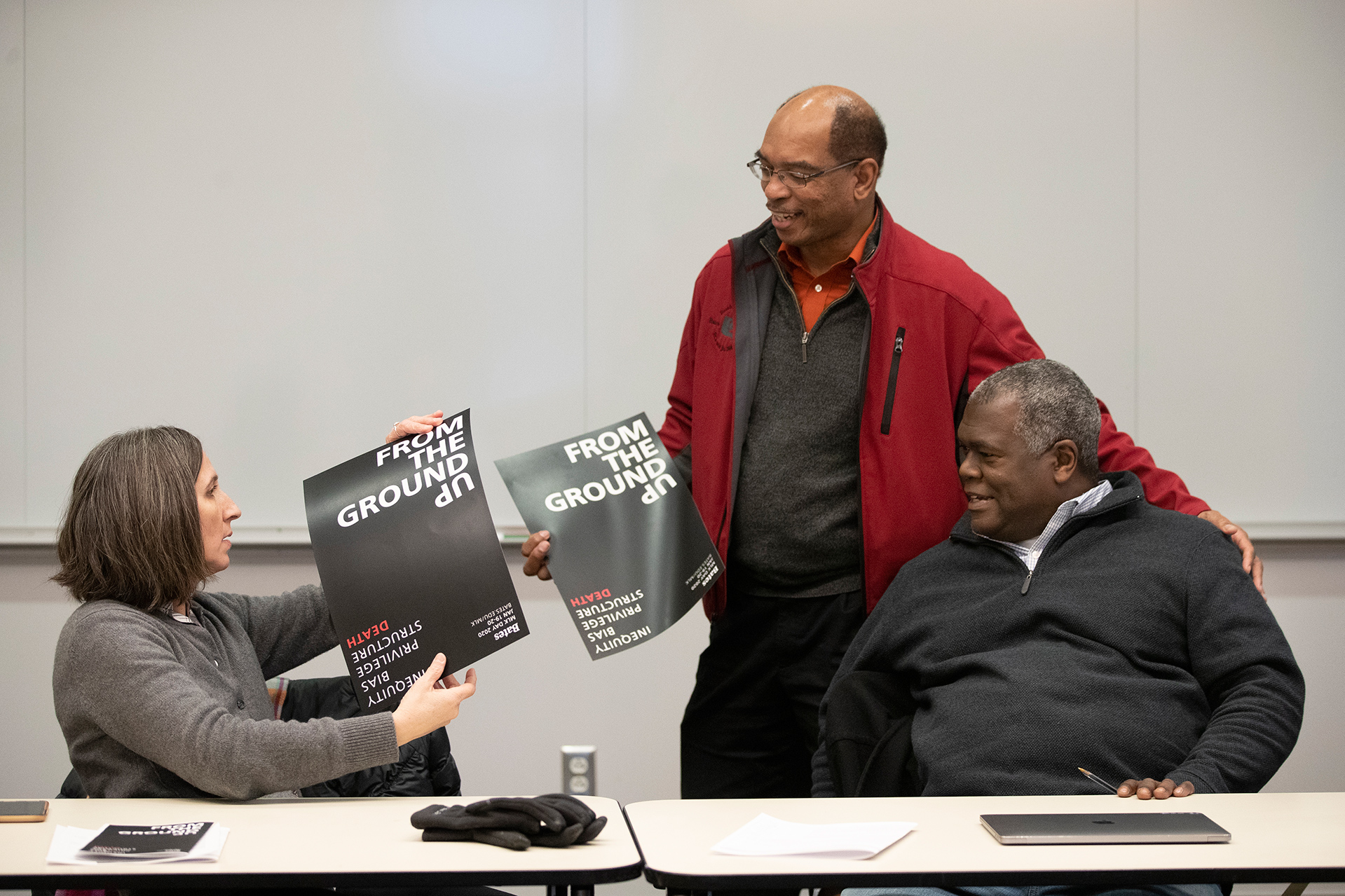

As Bates prepares to observe Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2020, those are a few of the presentations hewing close to the theme for this year’s programming: “From the Ground Up: Inequity, Bias, Privilege, Structure, Death.”

Beginning Sunday afternoon and concluding with an evening performance by the students of Sankofa on MLK Day itself, Jan. 20, Bates’ annual tribute to the moral legacy of the great civil rights leader stands out for its scope, thoughtfulness, and integrity.

2020 MLK Day Schedule at Bates

Bates’ distinctive celebration of MLK Day, from Sunday afternoon through Monday evening, includes the suspension of all classes on Monday to make way for programming to discuss, teach, and reflect on the MLK Day theme.

Offering this year’s keynote address is Jennifer Lynn Eberhardt, author of the 2019 book Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do. A 2014 MacArthur “genius grant” recipient and a psychology professor at Stanford, Eberhardt has conducted research revealing the disturbing extent to which racial imagery and judgments suffuse U.S. culture and society.

Sunday’s MLK Day programming includes the annual Sunday evening interfaith service, this year with the Rev. Dr. Theon Johnson III as homilist. On Monday, following Eberhardt’s 9 a.m. address, three sessions of concurrent workshops, panels, and presentations will feature faculty, students, and community members, plus an art exhibit, virtual reality experiences, and films.

An annual favorite, the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays, Class of 1920, Debate between students from Morehouse College and Bates takes place Monday afternoon, and the Sankofa production, Invisible Women, begins at 8 p.m.

In crafting the theme for this year’s programming, the MLK Day Committee at Bates sought to show that the work of undoing racism takes place on multiple planes, from the individual to the institutional to the national. From ground level, says committee co-chair and Associate Professor of Philosophy Susan Stark, “we need to build upward, reforming ourselves, reforming systems, all the way up to the ways nations interact.”

And given the depth to which “racism is infused into many systems in the United States, from healthcare to housing to criminal justice,” Stark says, we can’t forget “that the consequence of racism in those systems is often death.”

In her keynote, Eberhardt will review her work on Biased. MLK Day Committee co-chair Michael Sargent, associate professor of psychology, was a strong advocate for engaging the Stanford professor.

“I was excited about hosting a keynote speaker who does empirical work within the social sciences, and in social psychology specifically, as a way of demonstrating the potential relevance of that kind of work to struggles for social justice,” Sargent says.

He points to a 2014 study by Eberhardt and Stanford colleague Rebecca Hetey that demonstrated a distressing phenomenon. In the guise of a petition drive seeking support for criminal justice reform, they asked for signatures on one of two petitions — one illustrated with a photo set showing a high proportion of black people said to be prison inmates or one with a smaller proportion of black people.

“One might expect that seeing a disproportionately black prison population might lead people to be more supportive of reform,” says Sargent, “because they’re seeing the consequences, arguably, of highly punitive policies that have often led to that outcome.

“But what Hetey and Eberhardt found, interestingly and I think counter-intuitively, was the opposite.” Exposure to the petition representing a blacker prison population “did not lead to more support for reform, it actually led to less support,” he explains. Eberhardt and Hetey argue that a preponderance of black faces heightened concerns about crime and thus a desire for a more punitive criminal justice system.

If that came to pass, says Sargent, “you can imagine that those very policies that contribute to disproportionately black and brown carceral populations may actually enjoy not less but more support, as whites become more aware of who’s in those populations. So it’s a potentially vicious cycle.”

In devising this year’s MLK Day theme, “something that was really important for the committee was that it connect with Eberhardt’s work — so especially ‘bias,’ as well ‘privilege’ and ‘inequity,’” Stark says.

“And then also to have words that moved us toward thinking about racism as a system.” And systemic racism, she adds, has the “often underrecognized consequence for black and brown people that they live with more suffering and pain than their white counterparts, they experience more problems in healthcare — and they die younger.”

The MLK Day workshop sessions total more than two dozen. While all relate to the theme in one way or another, some exemplify it especially well. For instance, Stark says, one session — “Using K-3 Picture Books to Address Race and Racism With Children” — taps Bates’ unique Diverse BookFinder project, notably its 3,000-plus collection of picture books, for readings and hands-on activities with children and their caregivers.

“Children begin to manifest implicit bias” — unconscious prejudice that affects behavior — “around age 4 or 5,” Stark says. So exposure to children’s books that reflect real-world diversity “might make a difference in how they approach the world. And I think that is really from the ground up because it’s the youngest people.”

Sargent points to a presentation by Chad Posick, a criminologist at Georgia Southern University, that examines an incident involving a reading, by a Latinx author, that provoked a burning of her novel and subsequent counterprotests. The episode not only raises issues of white supremacy and free speech, but shows how they pertain across levels of analysis and impact, from the individual to the institutional.

And, Sargent adds, “I see Posick’s willingness to travel from Georgia to participate as a testament to how much he enjoys and finds engaging what we’re doing here on MLK Day.”

The Bates workshops examine social justice issues relating to Lewiston, to Maine, to the nation, and even to the world, in the case of the “Environmental Justice Mapathon” that will show how mapping technology can improve humanitarian responses to natural catastrophes.

Attendees can also undertake a practical exercise to counter racist attitudes, and see two plays, one written by Bates Lecturer in Theater Cliff Odle, depicting anti-slavery initiatives undertaken by black Colonial Americans. And they can hear about the practical and ethical issues encountered by Bates students who have served as translators for clients in the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project.

The workshops will invoke a variety of historic figures, from Dr. King to Gandhi to author James Baldwin. Media presentations will include films and two virtual reality experiences, including one by a Lewiston resident who documented his return to the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya.

The day will even feature a career-preparation component, thanks to the college’s Center for Purposeful Work, whose programming guides students in harmonizing their values, strengths, and post-Bates direction. In “Identity in the Workplace: How Does Who I Am Inform Where (and How) I Work?” Bates alumni will reveal how they have navigated their identities along their professional paths.

The panel, Sargent says, will encourage students to constructively consider identity as they ponder their course beyond college, “so they can align themselves with the kind of workplace that is going to actually facilitate their thriving.”