The racial bias that causes people to associate African Americans with crime, as social psychologist Jennifer Lynn Eberhardt explained to a Bates audience this week, even infects very young children — including, at one point, her own son.

Eberhardt recounted an episode on a flight several years ago, when her son was 5. Spotting another African American passenger, the youngster exclaimed that the man looked like his father. To an adult eye, Eberhardt told the Bates listeners, there was no resemblance.

And then Eberhardt’s son said, “I hope that guy doesn’t rob the plane.”

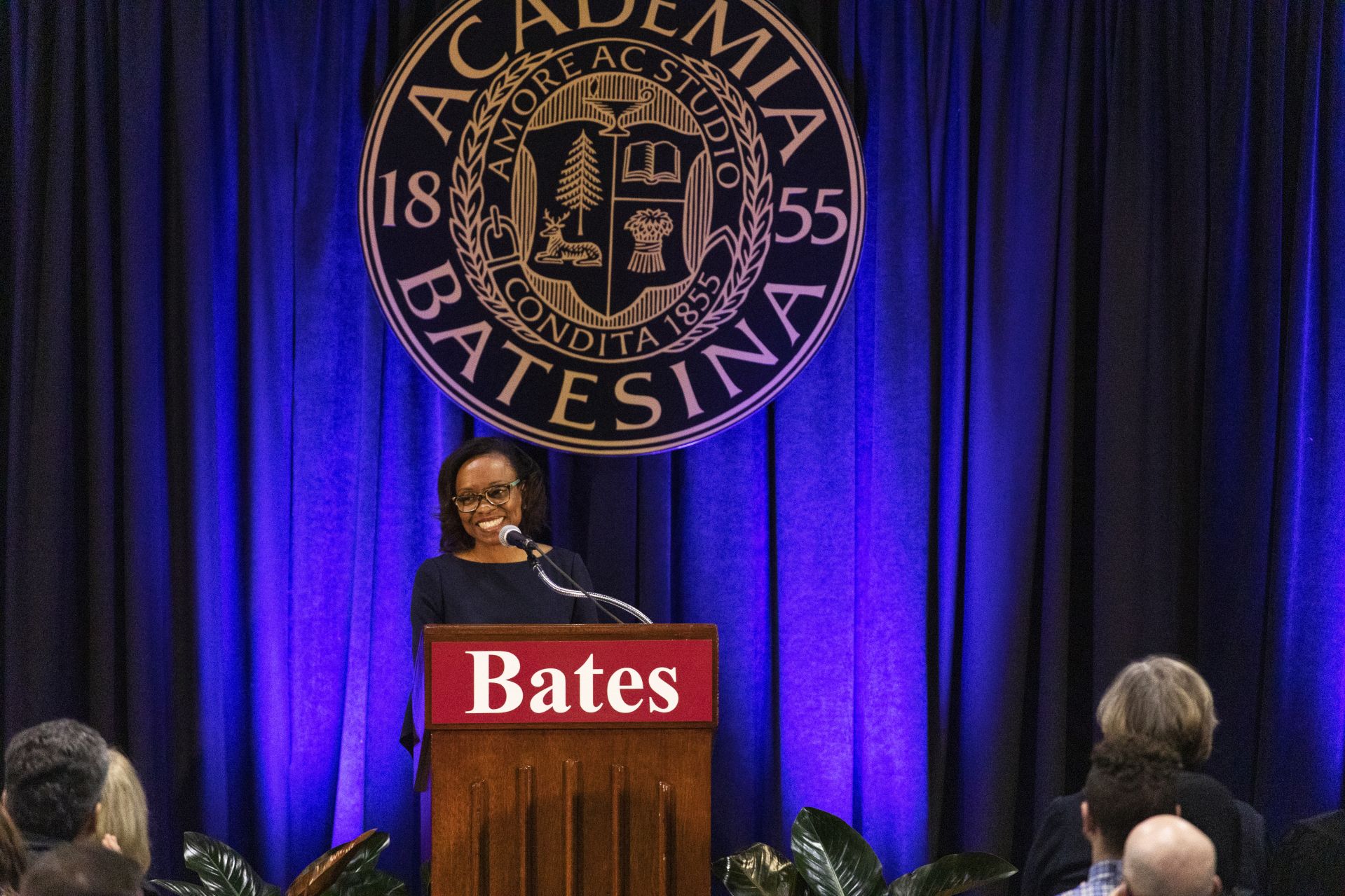

Jennifer Lynn Eberhardt, a social psychologist at Stanford University, delivers the keynote address in Alumni Gymnasium during the college’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance on Jan. 20, 2020. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“Why would you say that? You know Daddy wouldn’t rob a plane,” she retorted. “And he looked at me with this really sad face and he said, ‘I don’t know why I said that. I don’t know why I was thinking that.’”

So even 5-year-olds are already “caught in the grip” of the black-crime association, Eberhardt said Monday during a Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote address that was often sobering, at times poignant, yet ultimately uplifting. A social psychologist at Stanford and a MacArthur “genius grant” recipient, Eberhardt came to Bates to summarize research from her 2019 book Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do.

With about 700 listeners filling Alumni Gym (the traditional Gomes Chapel venue being unavailable due to ongoing restoration) Eberhardt’s lecture made a powerful beginning to a day of intensive Bates programming exploring the legacy and lessons of the civil rights icon.

Complete video of the MLK Day keynote at Bates College on Jan. 20, 2020.

The gathering began with welcoming remarks from college President Clayton Spencer and Alexandria Onuoha ’20 of Malden, Mass.

Introducing Eberhardt was Associate Professor of Psychology Michael Sargent, a co-chair of the MLK Day Planning Committee and, like Eberhardt, a social psychologist. Tapping the college’s mission statement, he gave a nod to that text’s language about the “transformative power of our differences” — but focused listeners’ attention on the words that come next, the call to cultivate “intellectual discovery and informed civic action.”

“When our words signal a commitment to social justice,” Sargent said, “there is a danger that by themselves, those words amount to nothing more than empty gestures. But informed civic action can give those words meaning.” By engaging with rich opportunities on MLK Day to explore well-informed civic action, “you will follow in the footsteps of Dr. King.”

Eberhardt explained that bias often isn’t subject to the rule of the conscious mind; instead, bias causes trouble and inflicts pain in defiance of our good intentions. Inviting her listeners on a “tour of empirical studies,” her own and others’, she devoted much of her talk to examples of how racial disparities evoke bias within a variety of systems — e.g., criminal justice, education, the economy.

Those research findings were sobering enough that the second part of the talk, dedicated to behaviors that we can learn to disrupt bias, provided a welcome sense of hope and encouragement.

In black-white relations, a powerful engine of bias is the profound association that people make between African Americans and crime. One of Eberhardt’s research projects, from 2004, involved three groups of participants, all of whom were shown what seemed to be flashes of light on a computer screen.

The MLK Day keynote address on Jan. 20 drew a full crowd to Alumni Gymnasium. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

For two of the groups, the flashes were actually images of faces that came and went too quickly for conscious recognition — a form of so-called subliminal priming. One group was exposed to black faces, one group to whites, and the third saw no faces at all.

Next, all participants viewed images of objects that were unrecognizable at first and incrementally became identifiable. The researchers tracked where in the series participants were able to name each object.

When the images depicted harmless items, such as cameras or staplers, the subliminal priming didn’t affect the participants’ ability to make out the objects. But when the images showed objects closely tied to crime, such as guns, the participants who’d been primed with black faces identified those objects much earlier in the series.

Eberhardt turned next to a 2007 study by researchers led by Joshua Correll. In this “Shoot, Don’t Shoot” project, subjects watched images of people holding either guns or harmless objects. They were directed to push a “shoot” button if they saw a gun, and a “don’t shoot” button if the object was harmless. (The Bates audience got a quick opportunity to try this exercise, slapping their right thighs for “shoot” and their left for “don’t shoot.”)

Correll’s participants “found, on average, that people were faster to shoot a black person holding a gun than a white person holding a gun,” Eberhardt said. “They also found that study participants were more likely to mistakenly shoot a black person who held no gun than they were to mistakenly shoot a white person.”

Bias often isn’t subject to the rule of the conscious mind, Stanford psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt told her audience on Jan. 20. Instead, bias causes trouble and inflicts pain in defiance of our good intentions.(Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

In schools, the black-crime association manifests, among other ways, as disparities in disciplinary action. Eberhardt cited studies demonstrating that teachers tend to expect more trouble from black boys, in particular, even at the preschool level.

“Black students are more than three times as likely to be suspended or expelled than white students,” she said. “And close to 70 percent of those black students who were pushed out of school end up in the criminal justice system at some point in their lives.”

She continued, “It starts early, and it has real implications for the mental well-being of black students and for their ability to achieve in school. Over time those students worry about how they might be treated in school environments. And those concerns can influence their day-to-day interactions with teachers and also their identity as learners.”

Meanwhile, even 17 years after an MIT study called out employers’ preference for white- over black-sounding names on resumes, job-seekers of color still must “whiten” their resumes — reduce a tell-tale name to an initial or omit college activities tied to racial identity — in hopes of evading such bias.

Despite this heavy burden of evidence of bias, there’s cause for hope. “I want to argue here that, although racial bias can touch our lives in so many ways,” Eberhardt said, “we’re not doomed to be under its grip.”

Instead, there are ways to maneuver through or overcome the circumstances, such as situations where people react reflexively, that can unleash bias. One tool is simply to introduce “friction” into a situation: slow people down so they can actually consider their responses.

The tech company Nextdoor, whose social media platform is intended to strengthen neighborly bonds, found that some people, instead, used the platform for racial profiling — reporting, say, that a black man was present in their all-white neighborhood. Eberhardt was among researchers who advised Nextdoor in developing a response.

Mahad Abdi Mohamed ’17, whose work in the Lewiston-Auburn area serves adults and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities, talks with Jennifer Lynn Eberhardt following her keynote address on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

While the tech world typically strives for less friction in its products, she explained, Nextdoor instead added apparatus that slowed the reporting feature, even if it might hurt business.

The company created a three-item checklist in the reporting mechanism. “The first item was asking people to state the behavior,” Eberhardt said. “It couldn’t be the person’s social category. It couldn’t be a black man. It had to be somebody who was actually engaged in suspicious behavior.” The second item asked for a description of the features, not the social category, of the individual being reported.

“And then the third item on the checklist was to define what racial profiling was,” Eberhardt said. “That one was interesting to me,” because a lot of the users “didn’t know what the definition of profiling was, nor that they were engaging in it.

“So they defined it. And then they also said that this is a behavior that’s prohibited on the platform.” And the checklist worked: “By introducing friction, they were able to reduce profiling by over 75 percent on their platform.”

Similarly, in the realm of school discipline, encouraging teachers to slow down and actually think about why a student might be acting out has proven effective, halving suspension rates in one study. Moreover, having just a single teacher go through that exercise caused students to view “their teachers in general as more respectful, and they trusted them more.”

Toward the end of her MLK Day address, Eberhardt quoted King: “Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” We have effective tools, she said, to counteract bias, to mend broken relationships from the ground up, “in our own individual lives.

“And our institutions — our police departments, our schools, our corporations — can use these same tools to make sure that everyone in the system can thrive and reach their potential.”

She said, “There’s a lot of power in just the simple things.”