It’s Friday afternoon, Jan. 10, and for professor Jane Costlow, a difficult moment.

She has just arrived at Pettengill Hall’s Perry Atrium, where an informal campus gathering will honor the memory of Carl Benton Straub, Costlow’s predecessor as the Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies. Straub died at age 83 in his Lewiston home on Nov. 15.

“Losing Carl is really hard,” she says. “He was just a dear, dear friend.”

A matted photograph provided guests with a glimpse of the young Carl Straub at the informal memorial gathering in Pettengill Hall’s Perry Atrium. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Costlow knew Straub for all of her 33 years at Bates, first as the dean of faculty who hired her, then as the faculty colleague who invited her to join the environmental studies program, and, ultimately, as a good friend and inspiration, if not quite a mentor.

“He was somebody I really treasured getting to talk with every couple of months,” she says. “I feel his absence, and as time goes by I’m going to feel it even more acutely. I need a Carl fix. I need to talk to Carl.”

And Straub thought so highly of Costlow that, before his death, he identified her as one of three individuals he wanted to eulogize him at his formal memorial service, to be held Oct. 10 in the Peter J. Gomes Chapel.

- Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College

- Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College

For Jane Costlow, the recent gathering for in memory of Carl Straub had pensive moments (left photo) and also laughter (right photo), where she’s flanked by Professor Emeritus of History Dennis Graflin, left, and David Das, her husband, right. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I’m really kind of glad I have a long time to think about what I want to say,” she says, “because it’s a daunting responsibility.” At the same time, “it also feels like a fabulous invitation from Carl to reflect on his life and what he gave to Bates.”

In Perry Atrium on that Friday afternoon in early January, Costlow was not among those who spoke about Straub, choosing instead to listen to others.

Though it was held for a sad reason, the gathering had moments of levity, notably recollections of Straub’s pointed observations about Bates life, everything from campus landscaping to the Commencement processional.

As a whole, the event was “a fabulous reminder of how much of a role Carl played at Bates and various other communities,” Costlow says. “He was a man of extraordinarily varied interests and friendships.”

Costlow, then professor of Russian and East Asian languages and literature, speaks with Straub and music professor Mary Hunter. The 2001 occasion marked Costlow’s appointment as the inaugural Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies. (Courtesy of Jane Costlow)

The gathering reflected that eclecticism, with friends attending from Bates; from the rural town of Sumner, where Straub owned property and made many friends; from the Shaker community, which he researched to understand that religious community’s connection to the land; from Maine environmental and arts organizations to which he belonged; and from the Lewiston-Auburn community where he lived.

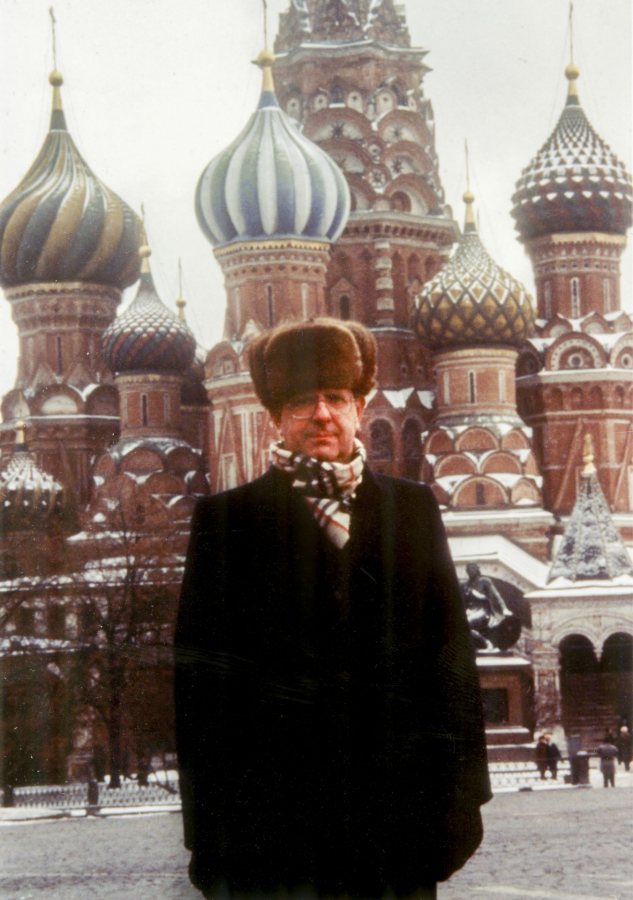

Costlow recalls that she and Straub hit it off from the start. Like her, he was fascinated by Russian culture, and because he traveled to Russia, the two had that point of connection. “There were a number of different things that we shared, interests that we had in common.”

Carl Straub, in an undated photograph, visits Moscow’s Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed, commonly known as St. Basil’s Cathedral. (Courtesy of the Carl Straub estate)

There were differences, too. In the classroom, Straub was a huge presence with a broad philosophical approach. “It was clear to me that I wasn’t going to be able to teach that way,” she recalls. “But it’s wonderful to have friends strikingly different from you.”

Straub’s being a larger-than-life Bates figure made it “almost too intimidating for him to be a mentor” to Costlow. Which made us wonder about the concept of mentoring: Who has mentored Costlow in her career? Who is a role model? And how is she mentoring younger faculty today?

You attended Duke as an undergraduate and Yale for graduate school. Who were your mentors or role models?

There were very few women as professors at Duke or Yale. For me, leaving high school meant leaving behind seeing women in the classroom, essentially. I went to a small high school in eastern North Carolina, where I also had African American teachers! None at Duke or Yale.

And when I was a graduate student in the mid-1980s, none of my professors, in the classroom, struck me as teaching how I would want to teach. They were world-famous, Ivy League scholars, and I don’t think they were that interested in what it would mean to teach at a liberal arts college like Bates.

Jane Costlow discusses her academic role models. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In that day and age, nobody got any training in being a teacher. It was, “Okay, here you are, here’s the deep end of the pool, now swim.” When I came to Bates, the people that I learned from were colleagues closest to my age, people like Georgia Nigro and Mary Rice-DeFosse.

And it was a very different age when it came to being a woman, having children, and staying at work.

I remember having a conversation in the library with Carole Taylor right after my first child was born. It had become impossible for me to write. And I was kind of freaking out because I was still untenured. She reassured me: “That’s completely natural. Don’t worry about it too much. You will be able to write again.” Those kind of short encounters made a huge difference to me.

And I remember potlucks for women on campus, staff and faculty, once a month, with those kinds of informal conversations — just debriefing, venting, and sharing. What was going on in class? What wasn’t going well?

Joyce Seligman, who founded the writing program at Bates, was extraordinary. It wasn’t that Joyce was mentoring or necessarily teaching us, although she had materials and insights about how to teach writing in the classroom. But she consistently gathered people together and created frameworks in which people could just share their experiences. Those were mentoring situations that for me were really, really helpful.

Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies Holly Ewing joins her environmental studies colleague Costlow on an afternoon walk. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Now that you’re a senior member of the faculty, how do you think of mentoring? Do you actively seek to mentor young faculty? How does that play out?

It’s somewhat informal. Occasionally somebody I know will seek me out, and we’ll have lunch or sit down and talk about a classroom situation, or balancing teaching, writing, and life activities — those kinds of things.

I think listening is the most important piece of mentoring, just being able to really give the person that you’re talking to a sense that they can say whatever is on their mind, in their heart, and to focus on listening to them, not giving advice too quickly.

Costlow greets Visiting Assistant Professor of Africana Cassandra Shepard in November. They share academic interests in issues around disasters: Shepard teaches about Hurricane Katrina, Costlow about the Chernobyl nuclear plant meltdown. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

But like anybody who’s been teaching for a while, I can make some concrete, tangible suggestions. And that’s certainly a form of mentoring, passing on what I’ve got in my bag of tricks. The language teachers at Bates have always been fabulous about doing that because language teachers think about that stuff: “Okay, how are we going to get our students to learn vocabulary? Well, here’s this bunch of stuff that you can do.”

Do you have an overriding philosophy for helping younger colleagues?

I want to just affirm people in being the teacher that they are. Early in my career at Bates, I had to come to terms with the fact that I was not going to be a teacher like the late Dick Williamson. His persona in the classroom was incredibly vibrant and big, with his amazing sense of humor and energy. I could not be Dick.

Costlow visits with Associate Professor of German Jakub Kazecki and Associate Professor of German Raluca Cernahoschi in Kazecki’s Roger Williams Hall office. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

But as I’ve matured as a teacher and become more experienced, I’ve realized that what’s important is to be the person that you can be. Let your personality become a persona in the classroom that works for you, and that makes you comfortable and makes other people comfortable.

And then you occasionally throw in a joke. Every once in a while I imitate a Russian babushka. And my students look at me like, “Oh my God, what has happened to her?” But it’s a moment of levity in the classroom.

Costlow meets in the Den with Emma Conover ’16, visiting campus to participate in a Purposeful Work panel about environmental careers. Conover works in the water program at Ceres, a sustainability-focused nonprofit. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The other night you moderated a Purposeful Work panel of alumni from the last 30-plus years whose careers are related to environmental work. Some of these alums you’ve known and mentored. What were your thoughts as you saw them addressing current Bates students in environmental studies?

It was wonderful to see former students who have made their way, in very different ways, into interesting and fulfilling work.

It’s wonderful to see how they’ve grown, since we knew them in our somewhat protected classrooms, to become flexible, resilient, creative, and imaginative — and then where they’ve gone with that after graduation.

Costlow moderates “Purposeful Work: Spotlight on Environmental Careers,” an alumni panel discussion in Commons. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The variety of things that they’re doing is really inspirational, and I was delighted to hear so many of them talk about the importance of storytelling and communication in their work. Everybody in every classroom at Bates is teaching these skills, and they’re clearly important once they’re out in these very different jobs and settings.