At the dedication of Olin Arts Center in 1986, the late Carl Benton Straub, then dean of the faculty, said that “none of us will ever know the countless moments of discovery and self-discovery which will occur in and around this place.”

We won’t know them all, but here are a few — images and sounds of artists and their art, musicians and their music, captured over three days in early February by Bates writers Emily McConville and Doug Hubley and photographers Phyllis Graber Jensen and Theophil Syslo.

The home of the Bates College Museum of Art, Olin Arts Center also houses the Department of Music and the Department of Art and Visual Culture.

Dedicated in 1986, the Olin Arts Center has been a home to art and artists, music and musicians, who “cut through pretense and presumption to fresh, new beginnings.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The building features classrooms and faculty offices; practice rooms for musicians and art studios including a ceramics studio and kiln room; a slide library of digital and film artwork and photographic darkrooms; and the signature 300-seat concert hall.

In the spaces of Olin, as Straub promised more than three decades ago, Bates artists and art, and musicians and music, will “cut through pretense and presumption to fresh, new beginnings.”

With that, we begin:

Wednesday, Feb. 5

Experimentation with Intent

If Bugs Bunny with his banjo or Bart Simpson with his skateboard seem so free and wild, the art that goes into their cartoon antics is anything but.

This is clear from watching Carolina González Valencia, assistant professor of art and visual culture, show a class in Olin 321 how an animated film is made.

8:48 a.m.

Michael Hogue ’20 of Chicago works on a project before joining his classmates for an animation course taught by Carolina González Valencia, assistant professor of art and visual culture. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

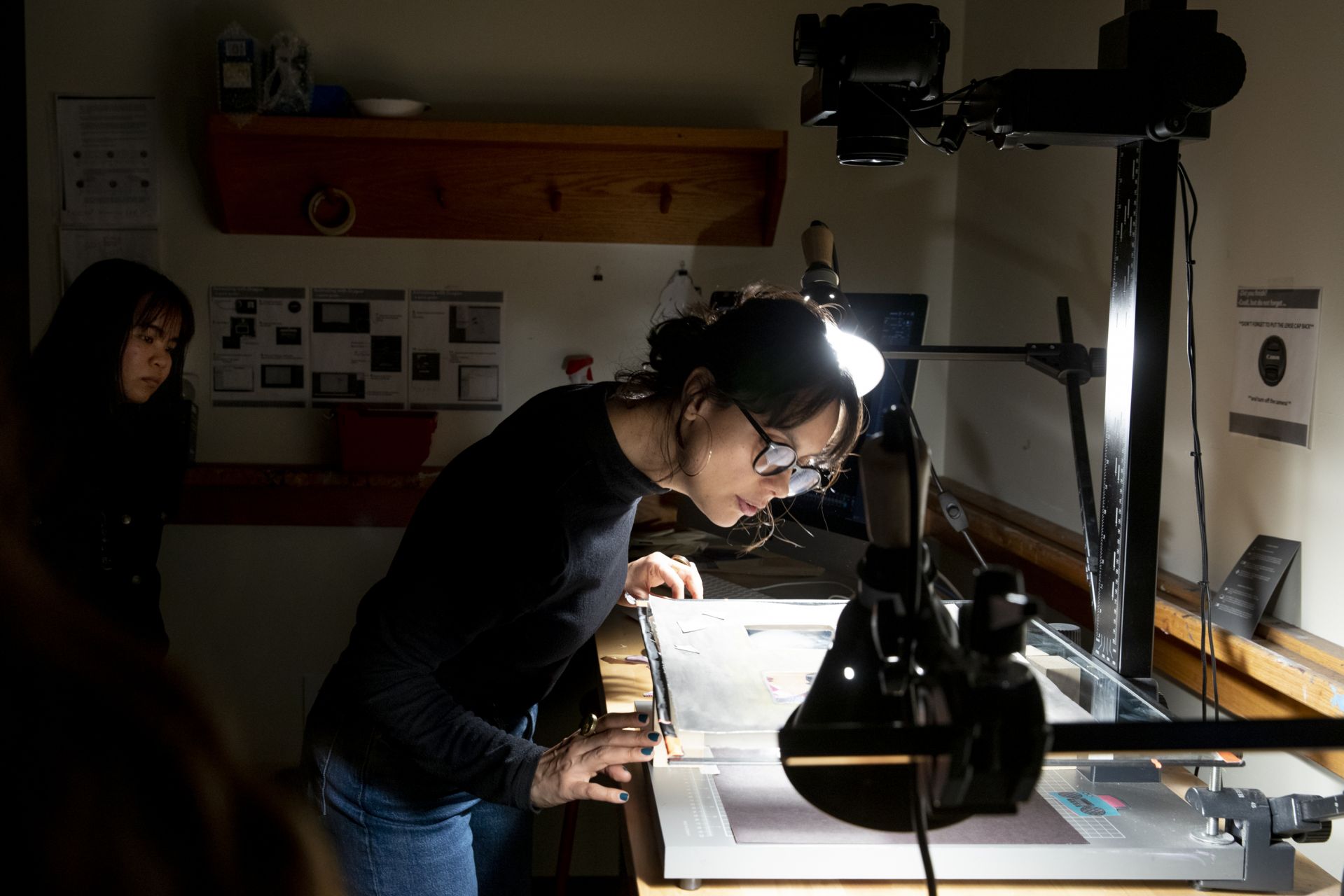

The course is “Animation II: Experimental Methods,” part of the animation track launched by the arts and visual culture department when González arrived in 2016. The animation lab, a former painting studio that still has a rail around the walls to support canvases, is tucked up under the sloping art center roof. The ceiling lamps are off.

Under the eyes of six students, González stands in a pool of light at an animation stand. At the bottom of the stand is a brightly lit baseboard marked with a grid, and at the top there’s a downward-aiming camera that can be moved up and down.

9:21 a.m.

Zhao Li ’21 of Guangzhou, China, watches the animated short film Recycled in Carolina González Valencia’s experimental animation class. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

González is demonstrating the use of cutouts and layers in a technique called under-camera animation. On the grid, she has created a scenario from a drawing of two open windows and a few cutouts — a banana, a paper plane, a dancer.

You know the drill: González snaps a few frames of the composition, which go into software called Dragon in an iMac. She moves something slightly and snaps a few more (the standard frame rate for animation is 24 per second). She creates illusions of distance by separating the visual planes with a sheet of glass, or by changing the camera height, or by substituting the paper plane with a smaller version.

9:23 a.m.

Carolina González Valencia, assistant professor of art and visual culture. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“When there are multiple things that I’m moving at different times, I like to keep a log,” González tells the students, who will soon be creating their own trial animations. In essence, her message is to bring the methods of science to this art form. Restrict the variables, she says. “Experiment with intention. Don’t move things in a random way.”

She plays back the frames she’s been recording, and a paper plane flies in one window and back out the other.

9:47 a.m.

‘One Really Cool Detail’

As they begin a visit at the Bates Museum of Art, education curator Anthony Shostak gives a class of seventh-graders from Lewiston Middle School two tasks as they take in the exhibition Miracles and and Glory Abound by Pittsburgh artist Vanessa German: Come up with at least one question about the art, and find “one really cool detail.”

There’s plenty to choose from. German’s work is immense, expansive, intricate. The middle schoolers are quick to point out the details, and their feelings about them. “That’s scary,” one observes about a pile of plaster baby legs adorning one sculpture. “There are keys everywhere,” says another.

10:55 a.m.

Lewiston Middle School student Michael Caron, 13, notices an unexpected part of a sculpture by Vanessa German: himself, reflected in one of the mirrors scattered throughout German’s exhibition at the Bates Museum of Art. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

This field trip is a kind of “field work,” says social studies teacher Jennifer Hudner. Later in the semester, the students will pick out a Lewiston landmark to personify. Hudner wants to show her charges that ordinary objects and structures can have great meaning.

“This” — Hudner gestures toward the whole exhibit — “has a lot of stories to tell.”

Museum education fellow Elizabeth Boyle gathers the students around the exhibit’s centerpiece, a sculpture of a boat and its passengers. The sculpture reimagines Emanuel Leutze’s iconic painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” depicting all of the boat’s passengers and the first U.S. president as Black women: “LaQuisha Washington Crossing the Day Aware.”

Boyle explains the characters in the sculpture — including a blue figure personifying water — and challenges the students to think about the importance of depicting Black women as part of a story from which they are often excluded.

Boyle says most tour groups catch recurring motifs like boxing gloves, keys, and mirrors. But German’s sculptures are so detailed, the symbolism so layered, that visitors often notice things before museum staff do.

Case in point: One student points out that LaQuisha Washington and the figure next to her look like a couple.

Practicing ‘Pathétique’

11:07 a.m.

The sounds of piano, a constant on Olin’s second floor, mix with that of a vacuum cleaner running on carpet. Alek Zelbo ’23 of New York City waits for a moment outside a practice room for his piano lesson to start.

Zelbo started piano about a year and a half ago, during a gap year before college. He took to the instrument so well that he hopes to major in music performance, as well as chemistry.

He’s on his way to reaching that goal — Bates students can take applied music lessons for credit — with the help of Chiharu Naruse, an accomplished pianist and piano instructor who studied under renowned Bates pianist Frank Glazer.

Vignettes from the Olin Arts Center practice rooms by Theophil Syslo.

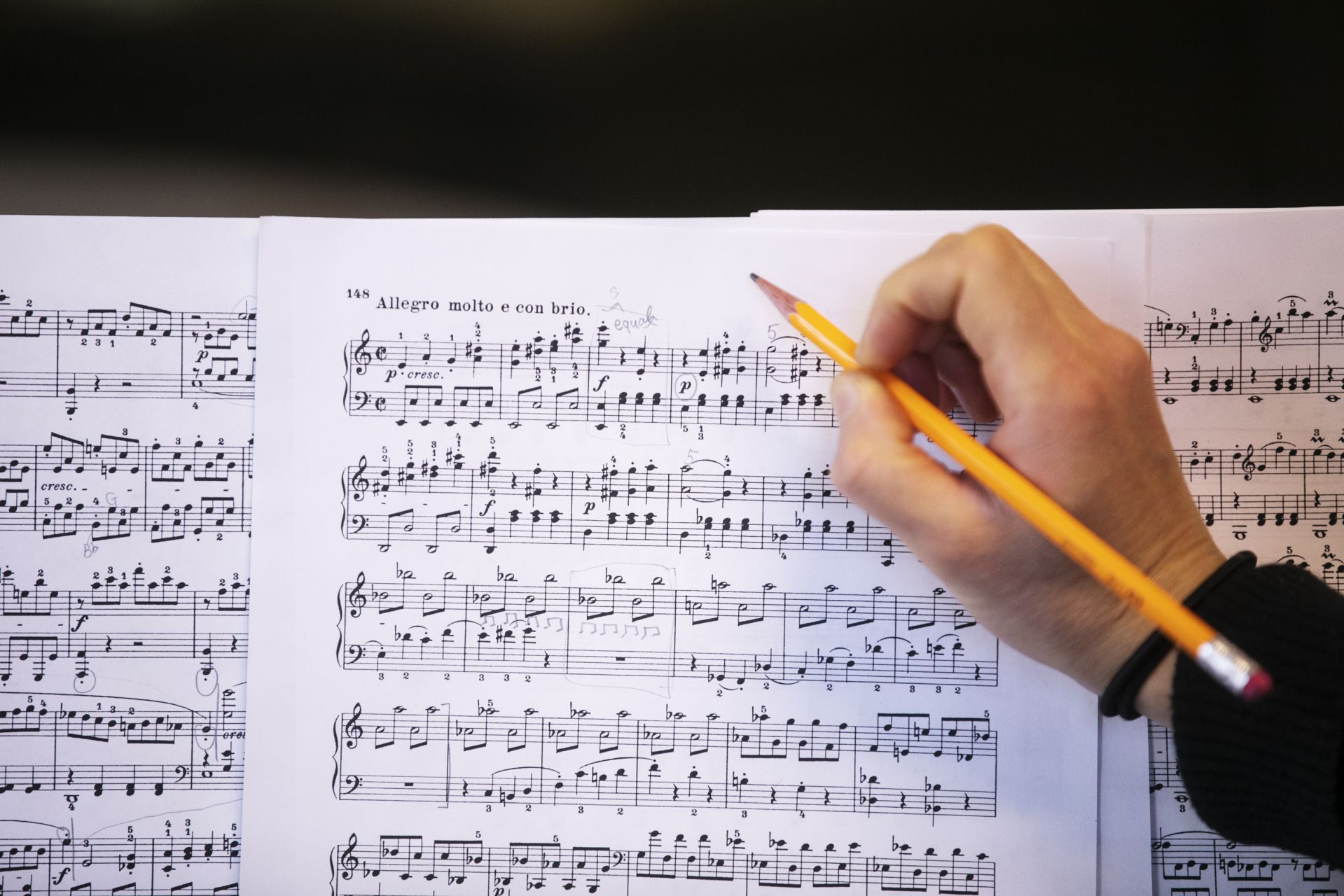

In the practice room, Zelbo runs through some scales before resuming a piece he’s been learning, Beethoven’s “Pathétique” sonata.

Naruse guides him through a section of the sonata, having him pay attention to volume, speed, and articulation — the clarity of touch. Both use pencils to make notes or tap out rhythms.

Several minutes into the lesson, Zelbo starts to play through several bars. “Yes!” says Naruse. “You can do it.”

11:16 a.m.

Alek Zelbo ’23 and piano instructor Chiharu Naruse use pencils to make notes and tap out rhythms. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

A Piece of the Puzzle

11:32 a.m.

Stay in the Olin Concert Hall for a week, and you see a revolving door of rehearsals; performances by students, outside artists, and artists in residence; and other events, with audiences of varying sizes.

Now, though, Olin is still and empty except for the hum of the auto scrubber, which custodian Bruce Audet uses to clean the stage about three times a week. He starts at an outer corner and works his way in; later he’ll need to move the piano that’s now in the middle of the stage.

Working in Olin is “like a puzzle, fitting everything together,” Audet says. There’s standard cleaning and maintenance, plus a carousel of events to set up and take down. Audet likes it that way.

He also likes being around students and employees, and the music and art they make.

‘Ohm’ in the Museum

The lower level of the Museum of Art is currently home to Ralph Meatyard: Stages for Being, an exhibition of the Kentucky photographer’s eerie, enigmatic images.

12:16 p.m.

Costume Shop Supervisor Carol Farrell performs a “downward dog” during lunchtime yoga in the Bates Museum of Art. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

It’s also the home of Wednesday lunchtime yoga for faculty and staff, including Costume Shop Supervisor Carol Farrell, Professor Emeritus of Mathematics David Haines, and custodian Mark Truitt. Surrounded by surreal black-and-white photos of children and adults in masks, yoga regulars roll out their mats.

Instructor Heidi Audet puts on some music, and the session begins. Roll shoulders. Straighten spine. Roll head, drop chin. Exhale — “hah!” Then cross legs, and, if you like, three rounds of ohm.

12:16 p.m.

Professor Emeritus of Mathematics David Haines, front, and custodian Mark Truitt reach up during lunchtime yoga in the Bates Museum of Art. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Duke’s Musical Dialogue

12:26 p.m.

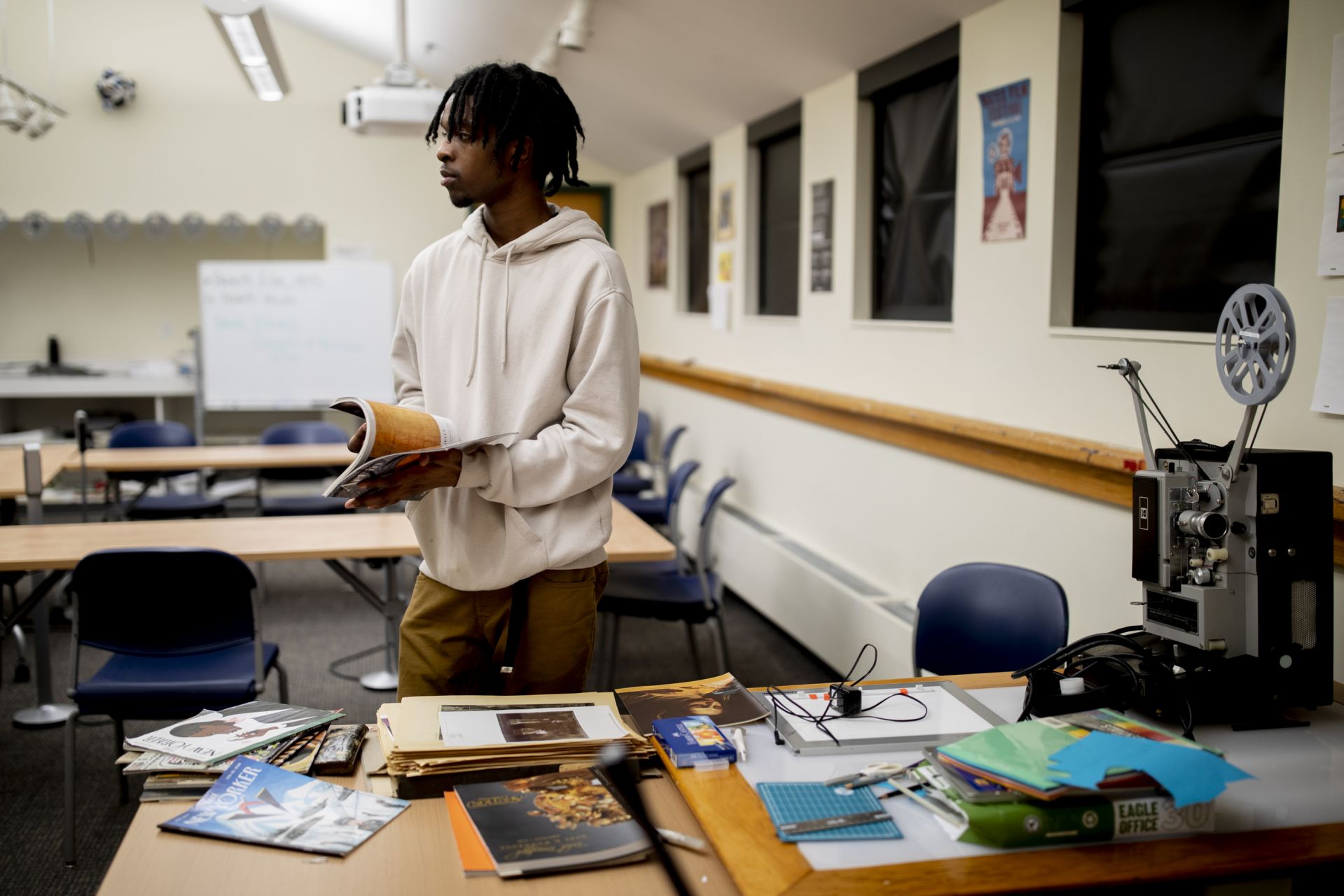

Olin 105 is set up as a small auditorium or movie theater. There are descending rows of seats, a raised stage with a piano on it, a sound booth in the back, and a wall-to-wall projection screen up front. Tucked away in a corner is an old overhead projector on a cart; nearby, a skateboard leans against the back wall.

In a course on the history of jazz, Associate Professor of Music Dale Chapman explains an upcoming writing assignment before starting a lecture on jazz in the Great Depression. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Associate Professor of Music Dale Chapman, teaching his jazz history course, is explaining how “exoticized, racialized” jazz performances gave way, during the Great Depression, to public dances, the audience becoming part of the entertainment instead of just watching it.

Emerging from this milieu was Duke Ellington, whose orchestra’s polished and sophisticated sound was thanks in no small part to trumpeter Cootie Williams.

Chapman plays a recording of “Concerto for Cootie,” an Ellington composition that gave Williams the spotlight.

Students in the class point out the dynamics of rhythm and loudness. Chapman adds that the piece contains internal harmonies, and that the rest of the band answers Williams’ melody — a musical dialogue, he says.

12:37 p.m.

Associate Professor of Music Dale Chapman discusses Duke Ellington’s “Concerto for Cootie.” (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

All Together Now

Wednesday afternoons are among the few times when the senior studios — rooms where studio art majors complete their thesis work — are full.

Seniors have 24-hour access to the building, and while each has times when they feel most productive and inspired, today’s the day when they meet together with Pamela Johnson, associate professor of art and visual culture, for their weekly thesis class.

E.B. Hall ’20 of Boise, Idaho, works on her pieces — grand sculptures and figurines made of donated clothes, Goodwill rejects, and even dryer lint — in a ground-floor room with wall-to-wall windows looking out on the field toward Russell Street.

A floor above, Mayele Alognon ’20 of Louisville, Ky., uses a wash technique to make semi-transparent figures on cardboard, many of them locked in embraces. “I’m juggling a lot with this idea that there are multiple authentic versions of self, rather than one objective version of oneself,” she says.

3:35 p.m.

E.B. Hall ’20 reflects on her senior thesis project — making sculptures and other artworks out of discarded items. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The studios are shared spaces, and among Alognon’s studio-mates is Philip Wu ’20 of New Taipei City, Taiwan, who across the room is using ink pens and brush markers to make intricate, dystopian cityscapes. Whereas Alognon likes to work in the afternoons (“I’m definitely with the light,” she says), Wu is more of a night owl, coming into the studio after dinner and working past midnight.

“I kind of like it to be quiet and peaceful,” he says. “That’s the environment I enjoy working in.”

“The energy’s always fluctuating.”

Alognon spends a lot of time in Olin, between the studio, her job at the front desk, and an independent study in animation. In the rhythms of the day, there’s “this friction between being a lot of noise in here and not a lot of noise,” she says.

“Sometimes it’s a really great place to concentrate on your own work and be by yourself, and sometimes there’s so much going on. The energy’s always fluctuating.”

It’s invariably nice, though, to come into the studio and see not only her own work, but that of her classmates. “It’s motivational to come in here and see what everyone else is working on. It makes you want to work harder and do better-quality and more work in general.”

Shedding Light

3:59 p.m.

As the late-afternoon light causes shadows to descend on the Olin lobby, Myron Beasley, associate professor of American studies, offers advice about summer jobs and art spaces to Ollie Penner ’22 of Pasadena, Calif., an art and American studies double-major.

Coming to Life

Live figure drawing starts at 6 p.m., and many artists arrive several minutes early. The nude model will pose on a small platform in Olin 259, with participants set up around her in a semi-circle — so where they place their easels will determine the angle at which they can draw her.

6:01 p.m.

A model poses during a weekly life drawing session in Olin Arts Center, sponsored by the Bates Museum of Art. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Sponsored by the Museum of Art, the three-hour session attracts both Bates students and community members — including noted landscape artist Joel Babb.

The model starts with a short five-minute pose. Using pencil or charcoal, the artists work quickly. Bodies take shape on paper within the first minute, followed by rough details and, for some artists, shadows.

6:16 p.m.

Landscape artist Joel Babb sketches quickly — the model’s first pose only lasts for five minutes. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

‘Got a Little Something’ to Play

7:24 p.m.

Tucked in a narrow room on the first floor, the 15 or so members of the Bates Steel Pan Orchestra play through “Got a Little Something.” It’s the ensemble’s first rehearsal of the semester. “Beautiful,” says director Duncan Hardy. “Wow.”

For the most part, each ensemble member is in charge of two steel pans, the Trinidadian percussion instruments. Made out of 55-gallon drums, the pans are marked along the rim with the note that will ring out if hit in that spot.

Watch the Bates Steel Pan Orchestra practice “Got a Little Something.”

It’s time to practice the next song, “Iron Have Me So,” and the room fills with the cacophony of musicians practicing their individual parts. Hardy circles the room giving instructions. Like steel pan music itself, the atmosphere of the rehearsal is lively, fun.

Bringing the group back together, Hardy has individual sections — high pans, low pans, bass — play parts of the song. Panners click their sticks as applause.

7:50 p.m.

From left, Sam Onion ’20 of Wayne, Maine, Emmy Daigle ’20 of Portland, Ore., and Steel Pan Orchestra director Duncan Hardy learn a new song. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Thursday, Feb. 6

Chipping Away

Alex Paton ’21 of Charlotte, Vt., breaks up snow and ice behind the outdoor soda kiln to make space for the kiln burners. This kiln creates a particular ceramic glaze.

2:25 p.m.

What Practice Is For

“We want the sound to be dense,” Alan Carr tells the low-end contingent — three trombonists and a euphonium player, plus a drummer — of the Bates Brass Ensemble. “Imagine the sound oozing through the wall, out under Russell Street.”

2:53 p.m.

Nick White ’21 of Brunswick, Maine, is one of three student trombonists in the Bates Brass ensemble. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Hidden in the back of Olin’s ground floor, the rehearsal room was built big but looks small, jammed with musical instruments. The musicians sit on folding chairs in a small clearing anchored at one end by two pianos. Carr, brass ensemble director and a trombonist himself, is conducting the students through an angular, propulsive passage from Martin Fondse’s “Low End HiFi.”

“There were four different E-naturals going on there,” observes Carr, unperturbed. This is what rehearsal is for, after all. When he adds his bass trombone to the ensemble, the sound densifies considerably. Trumpeters wander in or hang around, muttering in the hall. Drummer Christian Bradna ’20 of Guatemala City riffles his high-hat and pumps the kick drum.

2:54 p.m.

“How about we sing our parts?” Carr says. He claps the tempo, the men sing the dominant line, trombonist Alice Li ’21 of Bellevue, Wash. — despite her earlier claim that she’d forgotten the whole thing — negotiates an ornate counter-melody.

“Alice, that was perfect,” Carr says. He pauses. “Wouldn’t it be fun if we spontaneously sang like that during the concert?”

3:07 p.m.

Alan Carr, brass ensemble director, also plays bass trombone with the group. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Photograph Tasks

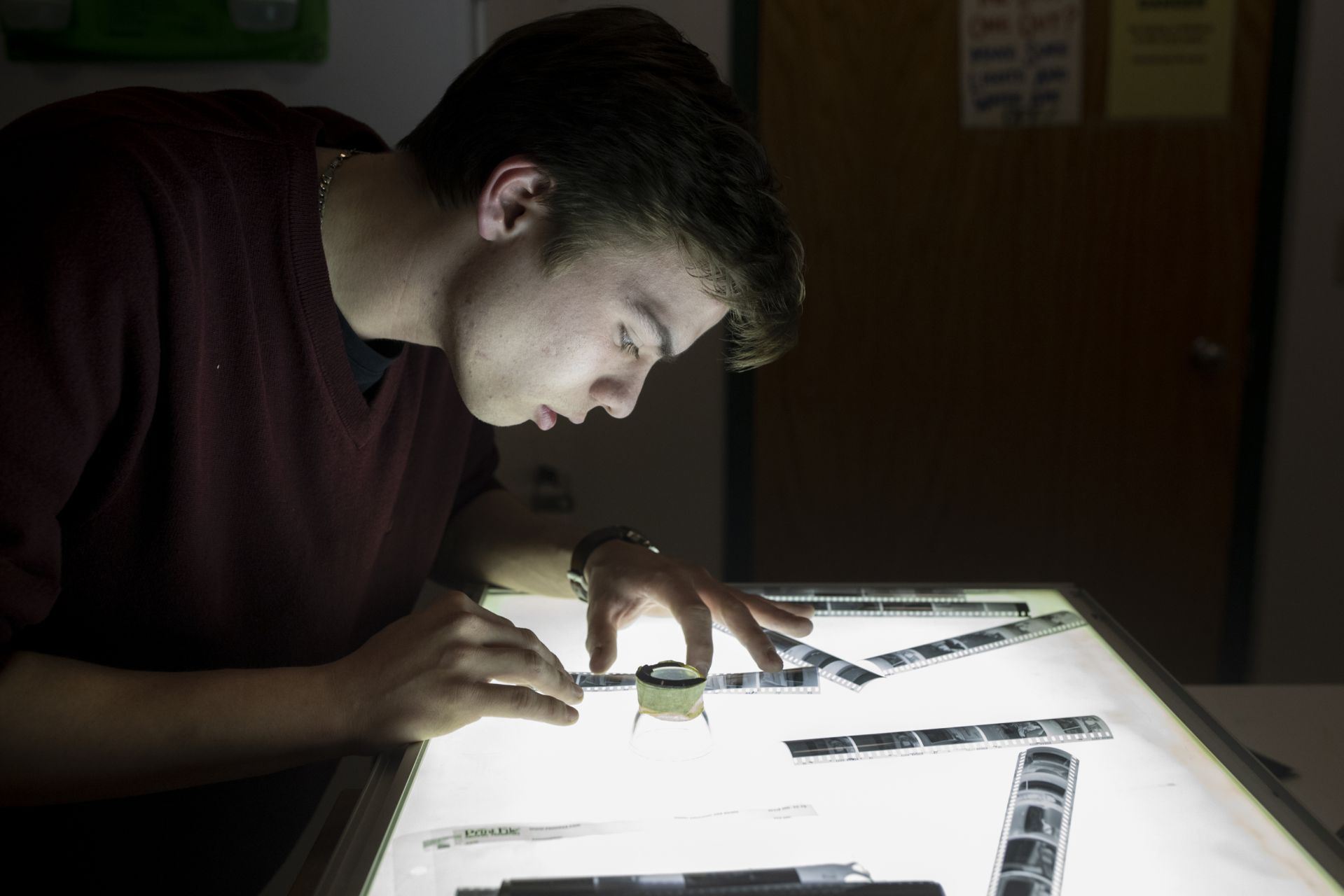

There’s an hour left in a three-hour photography course taught by Senior Lecturer in Art and Visual Culture Elke Morris; a special guest, Maine fine arts photographer Jack Montgomery, has offered to stick around and chat with students, including Jake Choi ’20 of Seoul.

3:19 p.m.

Otherwise, students in this upper-level class can consult with Morris about their assignment on photographing the human figure, or they can hang their finished work on the walls of the ground-floor hallway for the next day’s Arts Festival. The students scatter to their individual tasks.

Nick Charde ’22 of Concord, Mass., plans to showcase a series of photos he made during a gap year, mainly focusing on architecture. “I love the way a setting — the buildings, the trees, the people — comes together to form a composite,” he says.

3:23 p.m.

Cate Day ’20 of Montclair, N.J., talks with senior lecturer Elke Morris about her photography projects. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

An art and visual culture on the art history track, Charde has a class in Olin every day.

“I love the ambiance of this building,” he says. “You hear the pianos, people singing. It’s a good, cozy atmosphere. It’s away from the rest of campus, too, a nice alternative study spot.”

Johnny Loftus ’22 of Palo Alto, Calif., heads across the hall to the darkroom. The “film guy” in the class, he likes how film constrains his choice of settings and number of shots; his photos come out better in the end, he believes.

Loftus works late at night, sometimes coming in as the late-shift custodian is leaving. “You do your own thing in here,” he says — which helps his art.

3:26 p.m.

Johnny Loftus ’20 displays a binder of a classmate’s contact sheets in the Olin Arts Center darkroom. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

3:33 p.m.

Loftus uses a loupe to examine black-and-white negatives that he’s spread out on a light table in the Olin darkroom.

3:36 p.m.

Anna Gouveia ’22 of Jenkintown, Pa., hangs up her photo of a young boy in Lewiston’s twin city of Auburn. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I usually hear of it, and I’ll come.”

On evenings and weekends, when Alexandra Hood, the center’s operations supervisor, is away from the front desk of Olin, a battalion of capable student workers takes over. Sandia Taban ’22 of Changsu, China, likes the job because she gets to interact with lots of different people.

6:23 p.m.

Sandia Taban ’22 chats with Bates Communications employees during her shift at the front desk of Olin. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Among her duties: giving students keys to the ceramics room, helping people book concert tickets, scanning said tickets, answering prospective students’ questions. One time, a woman walked by the office, stopped, turned around, came in, and complimented the office plant. But Taban also has plenty of time to do schoolwork.

A nice side effect of working the front desk is that Taban is familiar with the arts calendar, so she goes to almost every concert. “Sometimes my friend will be in the choir, or my friend will be playing the violin in the orchestra,” she says. “I usually hear of it, and I’ll come.”

Percussion and Peace

Walking into the Bates Gamelan Ensemble rehearsal room, one feels a sense of tranquility. The wood and bronze of the Indonesian instruments cast a warm aura.

Even when the student and staff players are practicing individual parts of Sundanese songs all at once, the melodic percussion has, well, a nice ring to it.

6:36 p.m.

Nicole Recto ’21 of Laredo, Texas, plays kenong during the Bates Gamelan Ensemble rehearsal. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

6:37 p.m.

Of course, the group’s skill and practice really show when they master their individual sections, and are able to put it all together.

Watch a gamelan piece come together.

7:12 p.m.

It’s a familiar view to anyone who spends time in Olin Arts Center in winter: snowy Keigwin Amphitheater and an iced-over Lake Andrews.

Friday, Feb. 7

Handle with Care

“Our rule,” says Anthony Shostak of the Bates Museum of Art, “is that art objects are really safe when they’re not being handled.”

Fair enough. But inevitably, the museum’s Marsden Hartley drawings or pre-Columbian ceramics or Yvonne Jacquette prints, etc., actually do sometimes need to be handled. There’s a right way to do that and lots of wrong ways, and teaching the museum’s collection-management student interns right from wrong is an important part of their training.

1:19 p.m.

Anthony Shostak, education curator at the Bates College Museum of Art, shows intern Helen Pandey ’22 how artworks on paper are stored. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

This afternoon Shostak is giving that training to intern Helen Pandey ’22 of Nashville, Tenn., in the museum’s collection room, on Olin’s ground floor. Some precautions are self-evident.

For instance, gloves are worn to protect art from skin secretions, and they should be textured gloves for a good grip. Also, says Shostak, “If you have to cough or sneeze, definitely turn away.”

A so-called conveyance — in this case, a rolling table with an enclosed top — is used to, er, convey items from Point A to Point B. Three-dimensional objects like those old ceramics are swaddled in felt to protect them on the ride. Both hands are needed to carry an object, and don’t lift that ancient jug by the handle — it doesn’t need any more stress.

“Just be slow and crazily obsessive.”

Other art-handling tenets have a sort of “it takes a village” quality. Shostak always lets his co-workers know when he’s about to roll a loaded conveyance out of the collection room.

And if you’re up on the rolling ladder plucking a piece from an upper shelf, always hand the art down to a helper. Why? If you use both hands to hold the piece, you could stumble down the ladder. And if you use one hand to hold the railing, you won’t be using two hands to hold the piece.

“Whenever you’re moving art,” Shostak says, “just be slow and crazily obsessive.”

Encore, encore

4:46 p.m.

It’s the start of the Bates Arts Festival, a new student arts showcase and whirlwind of displays, demonstrations, workshops, and, of course, performances.

The senior art and visual culture majors are back in their studios together, showing friends and strangers what they’ve created. Students lead discussions of photography and poetry. The Bates circus club teaches curious passers-by how to juggle.

And the Olin Concert Hall features performances big and small, classical and modern, sung and spoken. The Robinson Players perform a song from their recent musical, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. The Crosstones bust out contemporary hits a cappella. The Bates Arts Festival is a showcase of student artistic creativity in its every manifestation — nurtured, in so many cases, in the Olin Arts Center.