It’s disparity day in Judge John Beliveau’s weekly law gathering on campus, and on this Thursday in February, about a dozen Bates students and staff members have read up on Supreme Court cases dealing with discrimination.

Beliveau, an active retired judge with the Maine District Court in Lewiston, asks one student in the Commons meeting room to explain Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 case that ordered schools to desegregate.

Another describes Korematsu v. United States, in which the Supreme Court upheld Japanese internment during World War II — widely regarded as one of the court’s worst decisions.

John Beliveau, an active retired judge with the Maine District Court in Lewiston, talks with students about Supreme Court decisions on search and seizure. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Beliveau peppers the presenters with questions: Who brought the case? How did it work its way up the courts? What was the court’s opinion? Were there any dissents?

To the side, his assistant, Ashley Koman ’22 of Burlington, Mass., clicks through a PowerPoint that illustrates each case with photos and quotations.

This Socratic method of questioning is typical of a first-year law school class, but these students don’t have to be interested in becoming lawyers to benefit from Beliveau’s decades of legal knowledge.

“The law should be accessible,” says Koman. “Judge B always says that everyone should take a class about this, to know your basic rights.”

John Beliveau chats in his chambers at the Maine District Court in Lewiston. An active retired judge, he still hears cases and often relies on Bates students like Ashley Koman ’22, left, as interns. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The lunchtime program, “A Judge’s Perspective on the Law,” arose in 2015 as a way for Associate Professor of Sociology Michael Rocque to add a legal dimension to one of his sociology courses.

Beliveau, an active retired judge for the Maine District Court in Lewiston, was the perfect volunteer. “Judge B” to students and courthouse employees alike, his legal career spans decades. He has worked closely with several Bates student courthouse interns and has long been involved with the Bates track and field program as a volunteer assistant coach and official.

“With my experience over 40 years, what can I do for young college students?” Beliveau says. “What can I teach them? What can I tell them about my experiences?”

The cases and statutes that Beliveau walks his weekly audience through encompass both the daily life of a Bates student and the social and legal forces that shape American society. There are lessons on landmark civil rights cases, state alcohol and drug laws, search and seizure, and voting laws in Maine.

A gavel rests on a plaque commemorating one of John Beliveau’s second jobs: mayor of Lewiston, in 1969 and 1970. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“We will go into current events,” Beliveau says. “We talked about impeachment, gun control, the First Amendment. We spent time on impeachment, because it was the thing.”

In the lunchtime sessions as in his courtroom, Bates students are “like my right hand,” Beliveau says. Koman helps the judge communicate with students and makes suggestions for the order of lessons — “easy” stuff like civil rights comes first, and then, once the group has gotten to know and trust each other, more-fraught topics like abortion and the death penalty

Koman is also an intern at the district courthouse on Lewiston’s Lisbon Street, primarily acting as a court reporter on family cases. It was attending Beliveau’s lunchtime meetings last spring that inspired Koman to get involved at the courthouse in the first place.

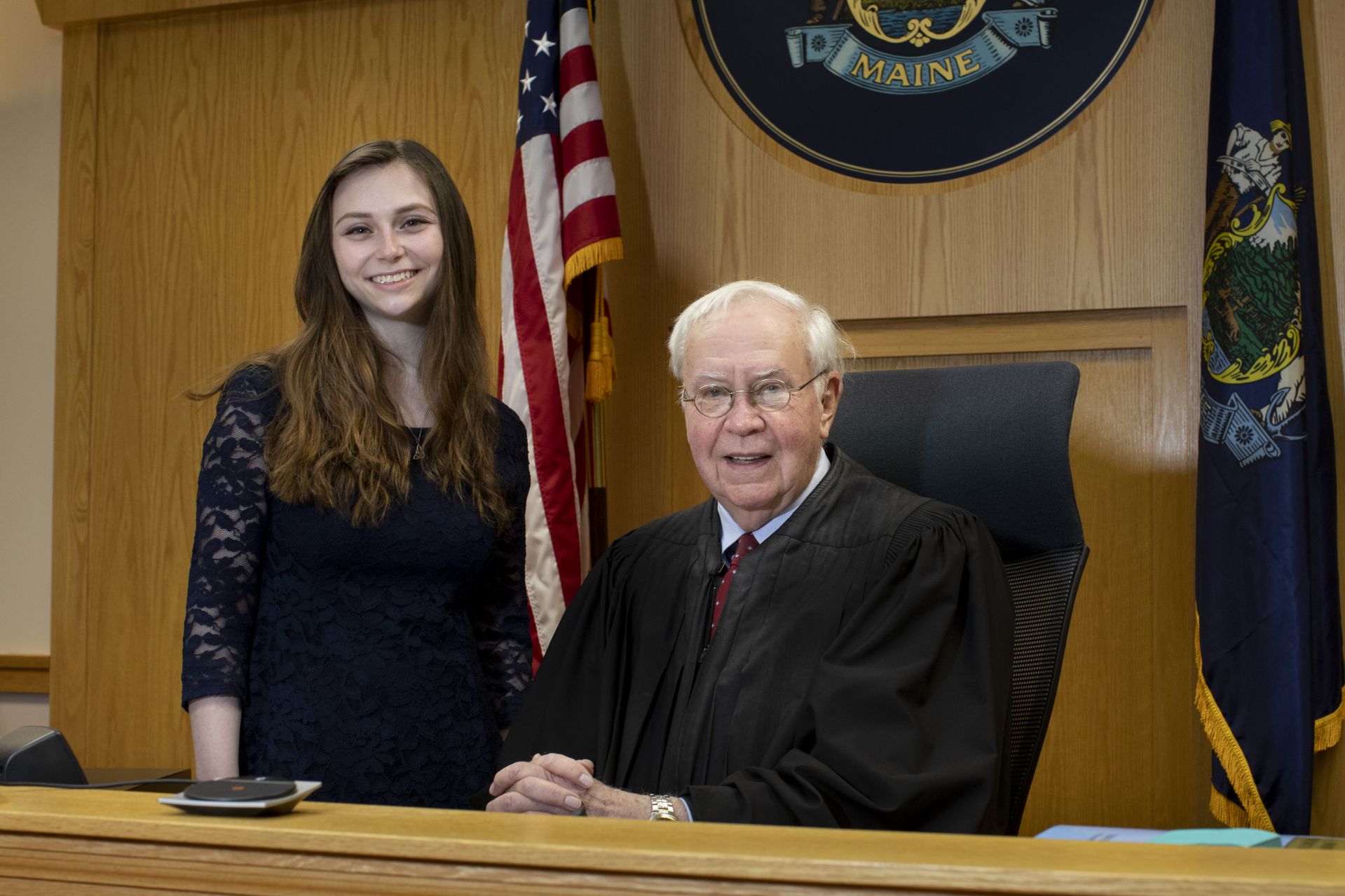

John Beliveau poses with with student intern and teaching assistant Ashley Koman ’22 of Burlington, Mass., in his Lisbon Street courthouse, where she records various hearings. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I took notes on everything,” she said. “I found it so fascinating. I used to read case briefs before class, eating breakfast, and it was the most enjoyable part of my morning each week.”

Though the seminar is still affiliated with Rocque’s sociology courses — his students can go to the gatherings and write a paper about them if they’d like — anyone on campus is free to attend.

“It’s important to know your fundamental rights,” Koman says. The offering is a “unique experience to study with a judge and a great, no-pressure way to be introduced to law in case it’s something you want to do.”