“Not all apologies are created equal,” says Ella Ross ’19.

The truth of that observation has become abundantly clear in the years since investigative reporting on movie producer Harvey Weinstein’s sexual misconduct kicked the #MeToo movement into high gear, initiating a sea change in how we talk about sexism, sexual harassment, and sexual assault.

The movement has resulted in the proliferation of public apologies by dozens in entertainment, media, business, and other fields who have admitted to misconduct.

As a Bates student, Ross joined Ceria Kurtz ’19, Talia Binns ’20, and Professor of Psychology Georgia Nigro to try to classify types of public apologies and determine what makes an apology effective.

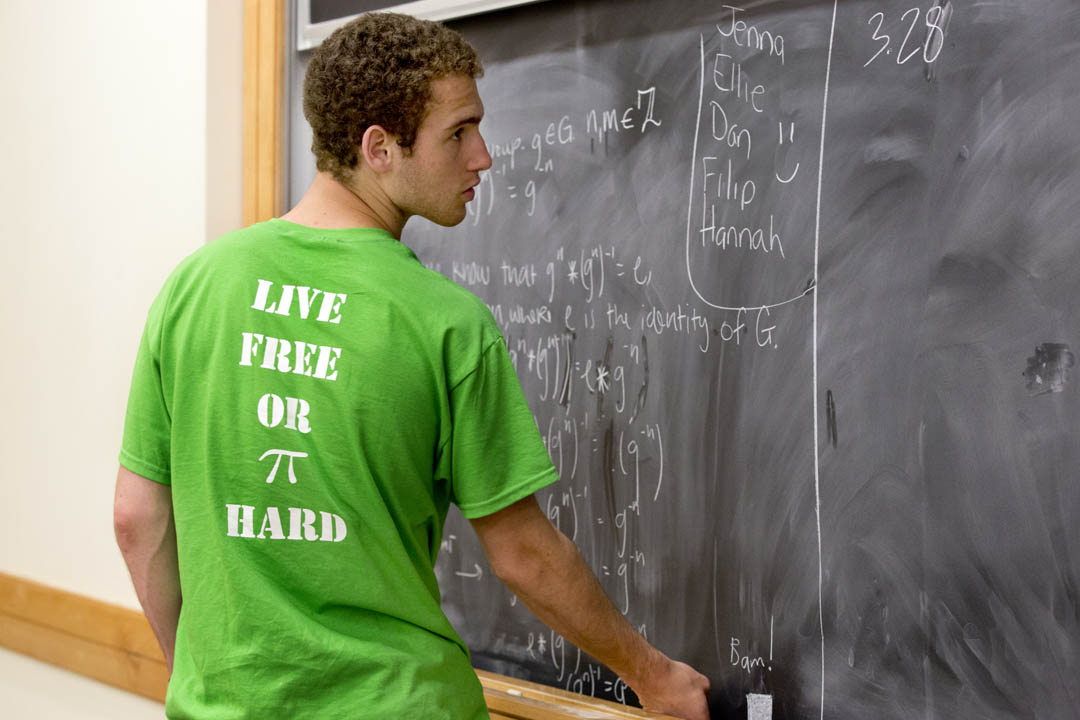

One effect of the #MeToo movement is a robust sample of public apologies for psychologists to analyze. (Wikimedia Commons)

The result of their independent research, “Apologies in the #MeToo moment,” was published last fall in the journal Psychology of Popular Media Culture.

“A good apology is a recognition of the ways in which you’ve harmed another person, with the emphasis being on the effects on the victim, not on how it’s impacted you as the offender,” says Ross, who is now the civic engagement fellow at the Harward Center for Community Partnerships.

To measure apologies, psychologists have identified several elements, classifying what apologizers say, the way they say it, and the concrete actions they take to repair the harm they’ve done.

In studying public apologies for sexual misconduct, the Bates researchers homed in on one subtle but important distinction: whether the apology is focused on the self, or on what they call the “self-other.”

A “self-focused” apology primarily expresses the feelings of the one saying sorry. In admitting wrongdoing, the apologizer might say, “I take responsibility for my actions,” and emphasize how badly he feels. “I am embarrassed and ashamed of my actions.”

Ella Ross ’19, a recent Bates graduate who now works in the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, talks with new students on Opening Day in August 2019. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

A “self-other focused” apology, on the other hand, takes the feelings of the victim into account. Instead of simply saying, “I did wrong,” the apologizer might say, “I did wrong, and as a result I caused people harm.” Moreover, the apologizer’s negative feelings would primarily focus on the victim. “I feel terrible that I caused you distress.”

The sample of apologies available to the Bates researchers shows the extent of the #MeToo movement and the entrenchment of sexual misconduct in many fields.

The news website Vox’s running list of people accused of misconduct contained 219 names as of June 2018, when Nigro and her students gathered the apologies they wanted to study (the list now stands at 262), but the researchers limited their study to 37 people in the fields of arts, entertainment, and media who had acknowledged or apologized for their actions.

“A good apology is a recognition of the ways in which you’ve harmed another person, with the emphasis being on the effects on the victim, not on how it’s impacted you as the offender.”

A key way psychologists evaluate apologies is by looking at how the apologizer plans to make amends with the people they harmed. In studying the 37 statements of apology, the Bates researchers had trouble finding actions that were self-other focused.

A person accused of misconduct might promise to go to counseling, or never harass anyone again — but could those actions repair the harm done to the victim?

“That was tricky,” Nigro said. “We spent a long time reading about, talking about, and never quite satisfied with the ‘action’ component, perhaps because there weren’t many actions that anybody took that were focused on the other person. The actions they took focused on themselves.”

In any case, many apologies that arose from the #MeToo movement had elements of both self-focus and self-other focus, though self-focus seemed to dominate.

Take one media figure’s apology for sexually harassing more than a dozen women over a couple of decades. American journalist Mark Halperin admitted that he was “part of the problem” of men harming women in the workplace and acknowledged the “fear and anxiety” he caused “women who were only seeking to do their jobs.”

According to the researchers’ classifications, one might see self-other focused acknowledgement of victims’ pain in Halperin’s apology, but also a self-focused explanation of Halperin’s own distress.

So which kind of apology — self-focused or self-other focused — is “better”? To find out, the Bates researchers wrote apologies of their own.

“You’ve got to do some reflection.”

They created a fictional but familiar situation in which a prominent film director is accused of sexually harassing several women. They wrote several apologies for the director to give to the women who accused him, similar in length and tone to the real ones they had already studied.

One of the director’s apologies was self-focused, one was self-other focused, one had elements of both types, and one added statements that were neither self- nor self-other focused, but rather seemed to justify or explain away the director’s conduct, such as, “I thought that the feelings I was pursuing were mutual.”

Nigro and her students then asked several dozen Bates students, as well as older adults on the Amazon crowdsourcing platform Mechanical Turk, to rate the quality of the apologies based on variables like perceived sincerity and willingness to accept the apology.

The types of apologies that most resonated with the participants differed according to age, gender, and whether the participant had identified as a prior victim of sexual assault. One thing, though, is clear: Apologies that focus only on the apologizer are not effective.

Talia Binns ’20, who helped run an experiment to determine how people perceive apologies, works on a ceramics project in Olin Arts Center. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“The sincerity of the apology, the willingness to accept it, the judgment that the accuser’s needs were met, and the sense of closure derived from the apology all fell short when an apology contained only the self-focused elements,” the researchers wrote in Psychology of Popular Media Culture.

For the Bates student researchers, parsing public apologies has informed both their academic careers and their personal lives. For her senior psychology thesis, Talia Binns looked further into how college-age men and women perceive apologies differently. She also understands “apologies in the media in such a different light,” she says. “I’m like, ‘That’s a bad apology.’”

Ross also parlayed her apology research into her senior thesis, creating a similar experiment in which she asked students to rate apologies related to an incident of sexual misconduct on a college campus.

Ross has also done more hands-on work on restorative justice, a system of justice prominent in some schools which focuses on rehabilitation and reconciliation. Because of her research with Georgia Nigro, she is better able to understand conflict and its aftermath.

Ceria Kurtz ’19, center, turns her tassel at Commencement in May 2019. Kurtz coauthored a study on the elements and efficacy of apologies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I know what questions to ask,” she says. “Was the person apologizing talking about how they affected another person, or were they talking about how they’re feeling? If they actually talked about just themselves and how it made them feel sad, I’m like, ‘That’s probably why the other person reacted so strongly against what they were saying.’”

Nigro emphasized that defining the elements of an apology is not the same as creating a formula for the perfect apology. “People need to learn from what they’ve done, but learning isn’t going to be so easy as, ‘I saw this thing in the news and now I know what to say,’” she says. “You’ve got to do some reflection.”

And in the media, on a college campus, or in a restorative justice setting, even a really good apology is only one part of making amends for wrongdoing.

“Sometimes the offender will just quickly jump to an apology because they’re ready to apologize,” Ross says. “They’re not taking into account the self-other aspect of it — ‘Does this person want to hear this? Are they in a place to receive it?’”