Jane Costlow struggles to find words to convey how she’s feeling. “In a way,” she says, “I don’t know how I’m feeling.”

In her 34th and final year in the Bates classroom, Costlow, the college’s Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies, has seen her in-person teaching career end in a way neither she, nor anyone else for that matter, could have ever imagined.

On Friday, March 13, Bates suspended in-person classes, asking all 1,700 students — except those granted waivers through petition — to move off campus in preparation for remote learning, which began on March 23.

During her 34 years of teaching, Jane Costlow has taught “Catastrophes and Hope” six times. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Costlow is no stranger to catastrophic scenarios. A day before the announcement, she led a discussion in her course “Catastrophes and Hope,” which explores disaster narratives that may serve as “dire warnings, offer glimpses of hope, spur us to change our lives, or scare us into denial.”

During that Thursday class, Costlow led a discussion of author Svetlana Alexievich’s collection of oral histories of the Chernobyl disaster, Voices from Chernobyl. She asked the students to imagine that Alexievich was interviewing them, because that’s what the author does, she explains.

“She interviews ordinary people who have lived through extraordinary circumstances. And so I asked them to write a piece as though Alexievich had asked them, ‘What was it like to be at Bates in March of 2020?’”

The idea for the writing prompt comes from experience. “One of the wonderful and frustrating things about teaching is that you’re always being confronted with new situations and new configurations of students. You have to learn to think on your feet.”

Costlow lays out the course landscape for her “Catastrophes and Hope” students on the first day of the winter semester. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

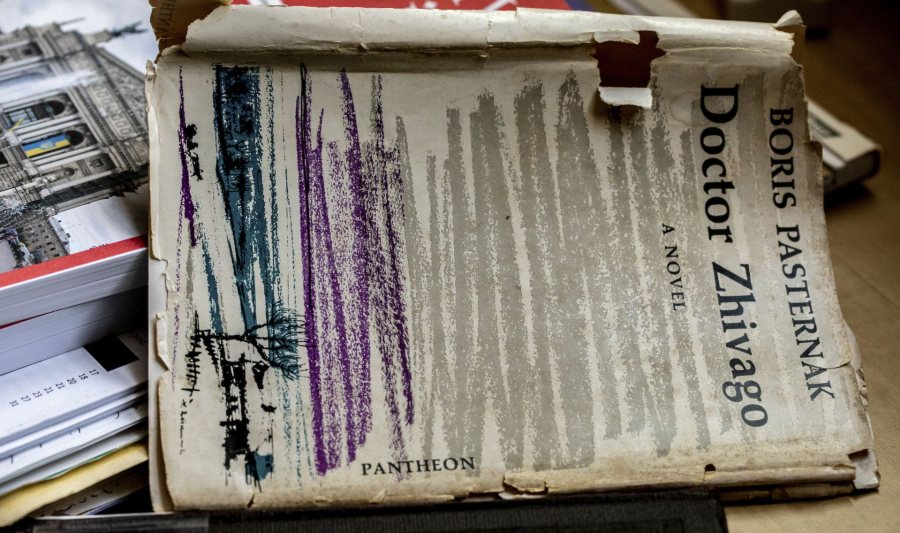

That last day in class, Costlow gave her students another, optional, writing assignment. Instead of a traditional paper, they could pretend to be a character in Doctor Zhivago offering written advice to the paper writer.

The novel’s fictional characters had “lived through profound psychological disruptions of revolution, civil war, displacement, separation from families, famine, and epidemic,” says Costlow, “people who have had the rug pulled out from under them really big time.”

Yet Costlow believes that the novel offers “profound examples of resilience and people’s will to live and continue.” That’s why she thought it would be interesting to see if some of the students would be willing to choose this alternative to a traditional paper.

A copy of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago sits on Jane Costlow’s desk. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The class accomplished, yet again, what Costlow has devoted her career to doing: giving her students insight, context, and understanding. She enjoyed the session immensely despite the circumstances.

But at home later that evening, knowing an announcement to close was imminent, Costlow finally reacted. “I felt really, really sad, because it hit me: ‘Oh, I’m never going to be in a classroom with students again.’ And I was just kind of overcome. It was the unexpectedness of it that made it really intense.”

Costlow has always known that humor can help calm roiled water; she reminds her students that “what makes human beings resilient in the long run is being able to tell jokes and share some kind of morbid humor with each other.” It’s part of what gets us through difficult situations, she says.

Although she kept the humor in mind on Friday after the closing announcement, Costlow found herself challenged in unprecedented ways, as students, some quite distraught, dropped by for goodbyes and reassurances.

At top, Costlow struggles with her emotions in her office with a student on the last day of classes. Above left and right, Costlow meets with Tommy Novick ’22 of New Canaan, Conn., and Ava Gulino ’20 of Wilmington, Del. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“It was excruciatingly difficult,” she said. “I just really wanted to go into my — I’ll call it a ‘maternal mode.’ I wanted to comfort them and hug them, but it was already kind of a situation where we weren’t supposed to do that. I felt powerless to care for them in a way I might normally have tried to care for them.”

But then a helpful realization kicked in.

Above left, Michelle Desjarlais ’22 of Albuquerque, N.M., also stopped by and received a social distancing–appropriate elbow bump from Costlow instead of a hug. Above right, Dianna Georges ’22 of Clifton, N.J., received Costlow’s reassurances that they would see each other again next year. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College) .

“There’s a continuity in my relationships with them as their adviser or their teacher.” In that role, she was able to calm and reassure them. “We’re not going to sit here and talk about your thesis, but we’re going to pick up and continue doing it online. The situation won’t be that different.”

And for those who weren’t seniors, she offered the consolation that although she won’t be teaching or advising them next fall, she will still be around to connect with them. “I’m not moving to the wilds of Russia. You will see me again.”

Those goodbyes remind her of a favorite Russian proverb: “Long, long goodbyes lead to too many tears.” It’s time to move on.

Costlow selected two volumes about Siberia, one about the people and the other about the formerly “forbidden territories,” for environmental studies major Tanner Stallbaumer ’20 of New York City. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

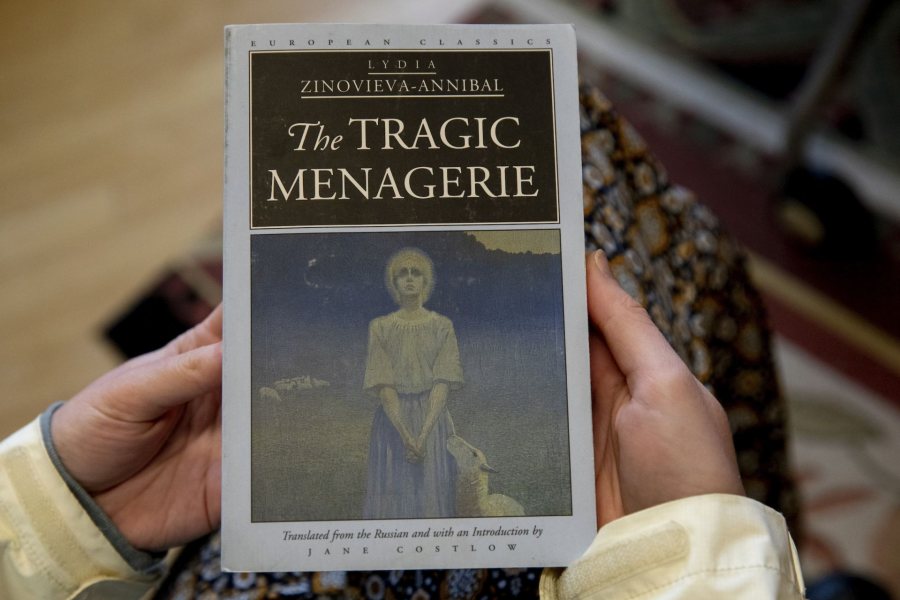

As her last campus semester evaporated in front of her, Costlow suddenly realized that she might lose the chance to engage in a traditional rite of faculty retirement: giving books from her office collection to students as gifts.

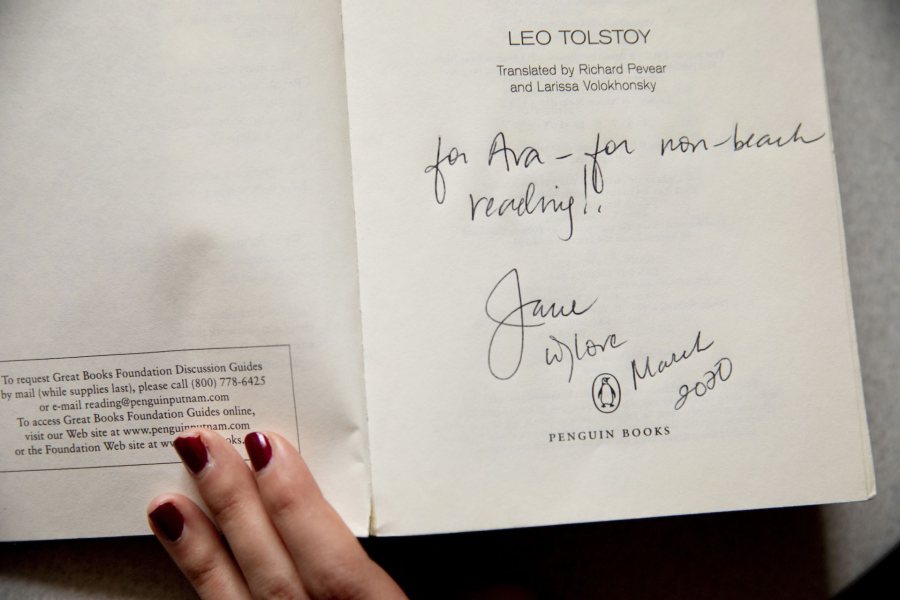

On that final Friday, one student left with two volumes about Siberia. Another received Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal’s The Tragic Menagerie, a book of Russian stories translated by Costlow herself. A third received a copy of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, inscribed by Costlow. “It’s a great time to dip into a fictional world that’s completely different,” Costlow said.

At top, Costlow’s sense of humor kicks in on March 13, 2020, as she suggests some reading, Roy Scranton’s We’re Doomed. Now What? Essays on War and Climate Change, for thesis advisee Ava Gulino ’20 of Wilmington, Del. Above left and right, Costlow pulled these volumes off her bookshelves and inscribed them for students as they dropped by her Hedge Hall office. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Now working from home in Auburn, Costlow has created a backdrop for Zoom meetings with students in her two winter-semester courses. Not a digital one, but a real one. There’s an antique pie safe — a tin bureau punctured with holes to keep the pastry aerated and bug-free, and a framed black-and-white drawing of a man with a hat, sketched 19 years ago by her son, Dinesh, then 12.

The Bates faculty had about 10 days to prepare — many for the first time in their academic careers — for remote teaching and learning. Costlow spent much of that week determining how to rearrange her syllabi, in part, by polling her students, 28 in one class, 35 in another, to get a sense of what their situations were.

Given Bates’ international student body, Costlow knew that “synchronous classes wouldn’t work because people are really all over the place.” She arrived at her approach through “a little bit of trial and error,” along with robust support from the college’s Information and Library Services.

Slowly, she felt less unsettled. She created short PowerPoint presentations to offer introductions and context for material. She’s divided the classes, including her course “Lives in Place,” into discussion groups of five and six students who discuss reading topics and then write blogs that are both responses to the readings and reports about their day-to-day experiences.

The blogs have been unexpectedly wonderful, she says, because there are some students who have opened up on the blogs, some of those who have been very quiet in class. “There’s an interesting way in which having a different medium of communication opens things up for certain students.”

In the midst of the second week of online teaching, she’s aware of what’s changed and what hasn’t. “I still have a stack of papers I have to grade. Right? I do need to sit here and read through them.” Yet reading their papers “is where I feel like I’ll encounter each student, personally.”

During a Zoom conversation, Jane Costlow describes how she felt when she realized she had just taught her last class in a Bates classroom. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

An unexpected benefit of remote teaching, says Costlow, is the opportunity “to get a little bit of a peek into their home lives.” To re-launch her classes, she asked students to create one-minute “re-introduction” videos about where they were and how they were feeling, and what they were experiencing.

“It was really great to see their faces and see where they are,” to be able to see their pets and their loved ones moving in the background. “That’s kind of cool. I think that you learn a little bit more about your students when you get a sense of them in the context of their family lives.”

But it’s also been clear that this new reality is, above all, stressful. Whatever their family’s circumstances, part of the stress results from “having gone off to college and become an independent adult. And then, suddenly, you’re back in high school mode, where you’re living in the house with the rest of your family.”

Remote teaching has presented entirely new challenges. A student asked her during a Zoom conference: “In your experience, has there been anything like this? Was it like 9/11?”

No, she told him. The pandemic feels very different to her “because of the time frame.” Sept. 11 was a series of events followed by shock and a subsequent “unfolding sequence of political disruptions and consequences.”

There was uncertainty after 9/11, but not interminable uncertainty of the kind we’re feeling now. We don’t have a sense of time.

As her students studied the Chernobyl disaster, they read an essay by the sociologist Kai Erikson, who describes what he calls a “new species of trouble” in the form of radioactivity and “toxic disasters.” Such events “don’t follow the law of plot,” Costlow says.

Costlow observes her “Catastrophes and Hope” students on the first day of the semester. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

With most disasters, such as floods or fires or hurricanes — the disasters that she lived through growing up on the coast of North Carolina — there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. “You know something’s coming. There’s confusion and complexity of whatever happens. Then the thing passes, followed by the aftermath.” Erikson’s conclusion, that toxic disasters don’t provide any sense of closure, resonated with Costlow’s students as they tried to make sense of COVID-19.

“There’s an amorphous sense of uncertainty about exactly what the disaster is and when, if ever, it was.” It certainly applied to Chernobyl, she says, but it also gave them language to consider for today’s pandemic. “Without the law of plot, there isn’t anything we can look forward to. I really can’t think of anything analogous to this in my own life,” she says.

People have been asking each other how they are doing, she concludes, and “we all kind of look at each other and say, ‘I have no idea.’ I mean, it’s kind of numbing. The structure of trying to do this semester is in some ways comforting, but I just can’t get over how strange and unsettling it is.”

She worries about her students, the college, and her colleagues. “It’s been very gratifying to see the extent to which faculty have reached out to each other online to try to provide advice, but also support for each other.”

But in the end, she says, “I don’t know. It just feels unreal.”