Meet Alonzo Garcelon, the Anthony Fauci of his day.

We know Garcelon as the 19th-century Lewiston civic leader who persuaded Bates founder Oren Cheney to locate his new school in Lewiston. Garcelon later served as Maine governor. Garcelon Field is named for him.

But Garcelon was also a famed physician who saved the day in 1840 by taking quick action to stop a smallpox outbreak in Minot, a small town near Lewiston.

Dr. Fauci, the ubiquitous National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director, has told us about fighting the COVID-19 threat: “If it looks like you’re overreacting, you’re probably doing the right thing.”

It seems Garcelon had a bit of Fauci in him.

Alonzo Garcelon, seen later in life with his daughter on East Avenue in Lewiston,

drove his one-horse shay to see patients all around town. (Muskie Archives

and Special Collections Library)

In 1840, fresh out of medical school and called to help the citizens of Minot, Garcelon immediately quarantined the sick and exposed persons. He then set about creating a vaccine — from his own cows. He later urged Lewiston businesses and schools to bar attendance by anyone without a smallpox vaccination.

Just as communities worldwide have, for eons, confronted infectious diseases — and overcome them as communities working together — so too has the Bates community. Here are a few instances:

1885: “Puncturation” exercise

The November 1885 issue of The Bates Student noted one of the first times wide-scale vaccinations were administered on campus, likely for smallpox. That year’s inoculations were a source of humor for the student newspaper. “Vaccination exercises were held at the lower chapel,” which in those days was in Hathorn Hall. “The chief ceremony was a ‘puncturation’ exercise by the doctor.”

1903: “Careful attention to sewerage”

In his 1902–03 president’s report, George Colby Chase proudly reported that “probably no other college in the country maintains a higher record for health.”

Probably thinking about deadly waterborne diseases of the age, such as cholera and typhoid, he said that “the natural drainage [of the campus] is excellent, and careful attention has been given to sewerage.”

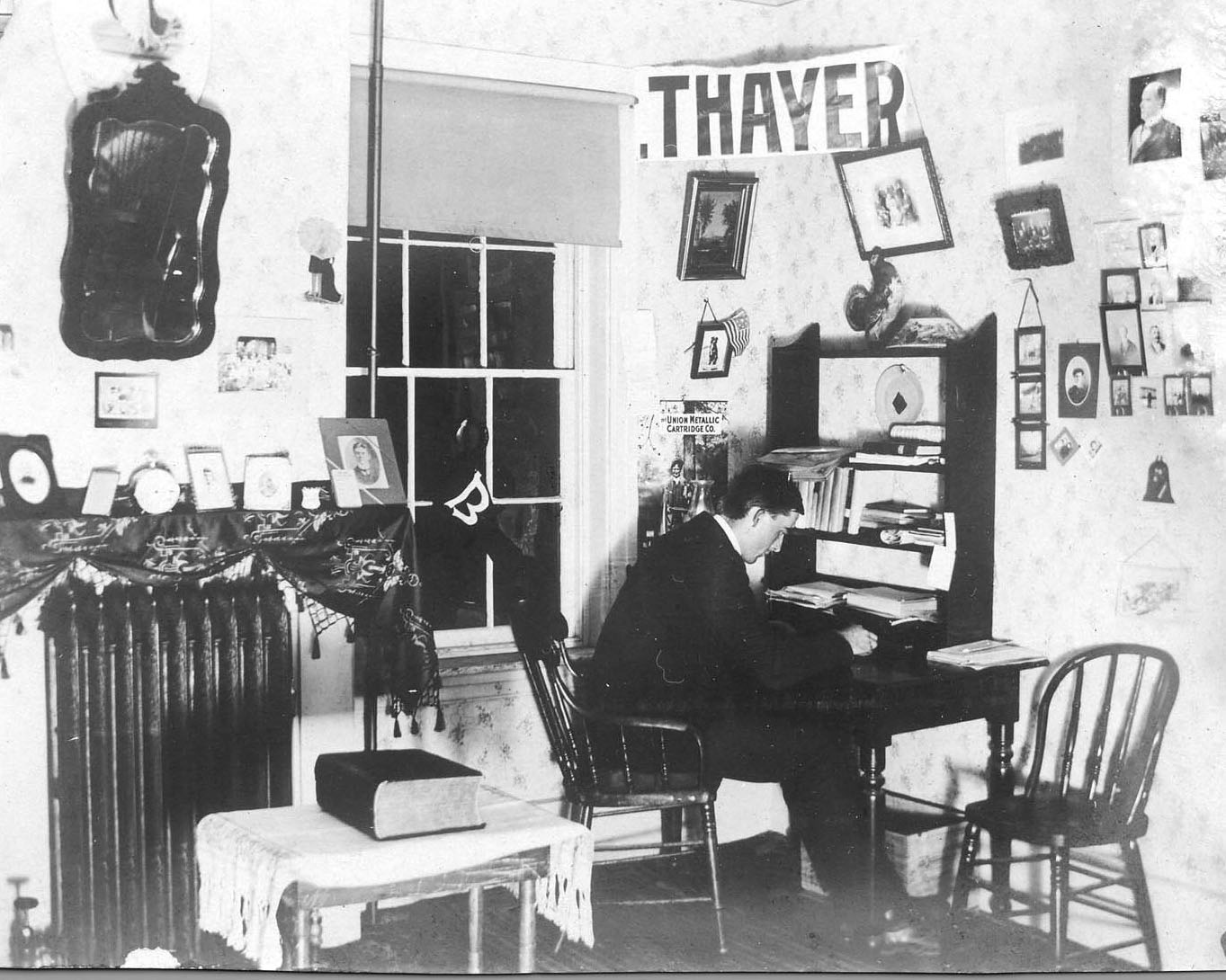

In 1903, Harold H. Thayer, Class of 1903, studies in his Parker Hall room. While the college was healthy, the young men in Parker could use “more watchful care,” said President Chase. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Yet there was room for improvement. “There has existed some danger of infectious diseases at times through the carelessness of the students occupying Parker Hall,” he reported.

“This fact, together with the temptations to disorder among inexperienced and thoughtless young men” — a set of curious euphemisms — “suggests the possible wisdom of a more watchful care over the Hall.”

1907: “Some outside institution”

Cheney House, then a women’s residence, was quarantined in 1907 for a time due to diphtheria, a bacterial illness now largely eliminated thanks to vaccines, which was “brought in by some outside institution,” the Student said.

Again, the college credited its excellent drainage and sewerage system with stopping the spread, though diphtheria is more of an airborne disease spread person-to-person by respiratory droplets.

Circa 1897, women of the Class of 1897 pose outside Cheney House: Mary Buzzell, Margaret Knowles, Emma Chase, Mabel Winn, Anna Snell, Caroline Cobb. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

1918: “The avoidance of crowds and careful cleansing”

The global 1918–19 influenza pandemic, which killed around 675,000 Americans and many millions worldwide, came in three waves, the deadliest being the second, in fall 1918.

The Bates Student, in its debut issue of the academic year, Oct. 18, 1918, reported the recent deaths of five alumni, four of them in the military.

Two died at Massachusetts hotspots later identified as the source of the deadly second wave. Army soldier Mellon Adams, Class of 1916, died at Camp Devens, an Army training facility west of Boston. Roland Purinton, Class of 1917, who died at a Boston hospital, was among 21,000 Navy personnel stationed in Boston.

“On the first Friday of the year, a case of influenza appeared. For weeks thereafter every energy was bent to securing proper care for the sick.”

In Maine, more than 2,500 people died in October 1918 alone. In Lewiston, most businesses and gathering places were shut down, and the campus was quarantined most of the month.

Even so, the flu hit campus hard that month. “On the first Friday of the year, a case of influenza appeared. For weeks thereafter every energy was bent to securing proper care for the sick,” said Chase in his 1918–19 president’s report.

Most of the cases, about 40, were among female students. Frye House, at 36 Frye St., and the top floor of Rand Hall, a women’s residence at the time, were turned over to the sick.

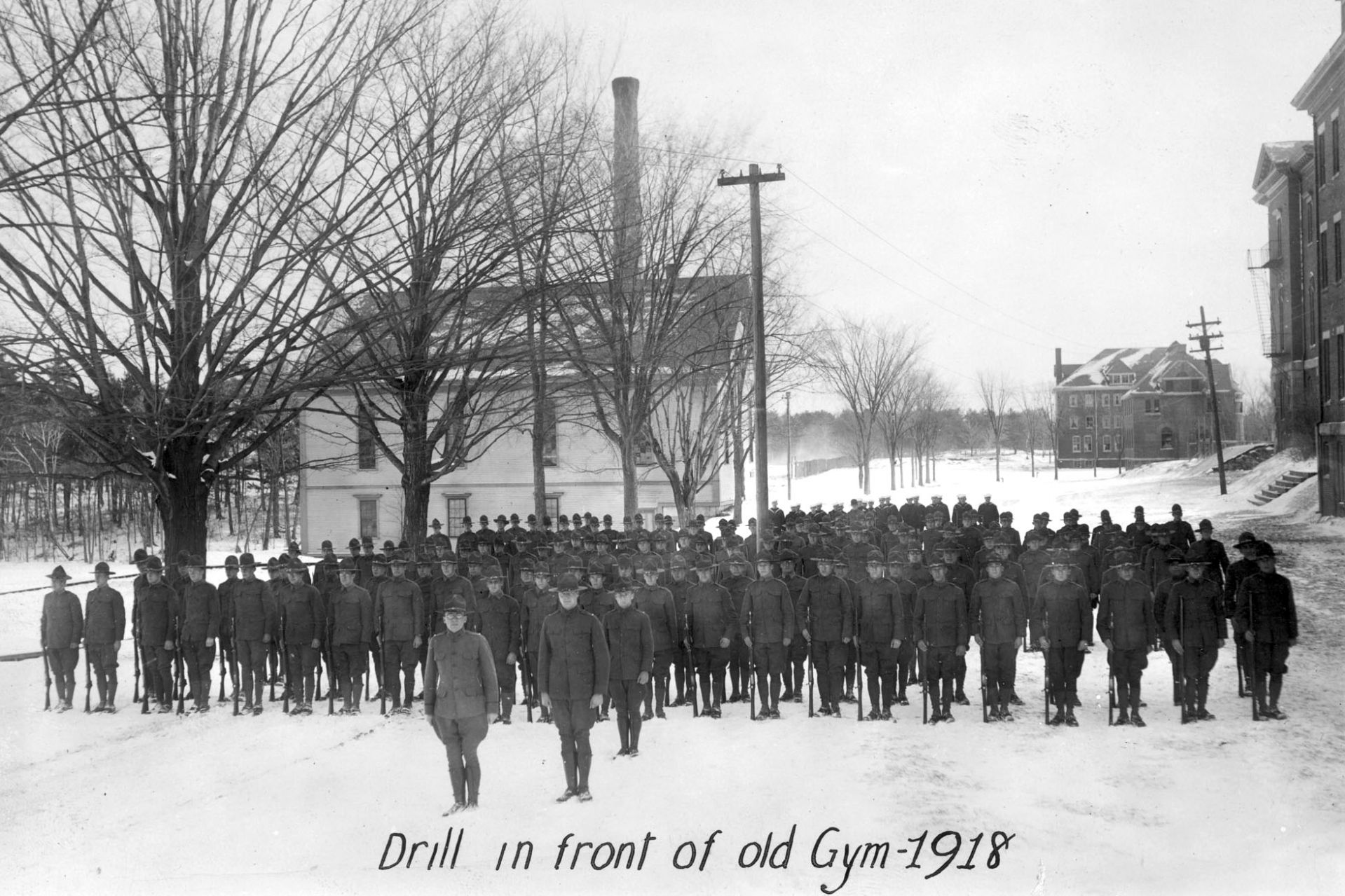

Perhaps helping prevent cases among men (dorms and many activities were single-sex in those days) was that many were part of the Student Army Training Corps, similar to today’s ROTC. About 150 male students, or about a third of the student body, were SATC trainees, and they lived life under strict Army command — and heightened protocols.

Members of the Student Army Training Corps go through drills in 1918 behind Hathorn Hall. The old wood-frame gym is at left. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Case in point: During the quarantine, obligatory chapel services for the men, presumably including those of SATC, were held outside, “in the open,” in front of Parker, rather than in the Chapel. The women had their services in the Chapel “as usual.”

For the SATC soldiers, Parker Hall was one of their “barracks.” The Student exhorted students to follow “rules laid down by the authorities and keep the barracks free from disease,” emphasizing that “the avoidance of crowds and careful cleansing — these are the best preventive that we have.”

There was a strong belief in the value of fresh air in fighting the flu spread, a view that has some medical support. In the Parker barracks, windows remained open all night. A student recalled a cold and windy morning with the windows “wide open, so that the above mentioned wind can sweep through the rooms in all its fury and thus keep colds and other ills away.”

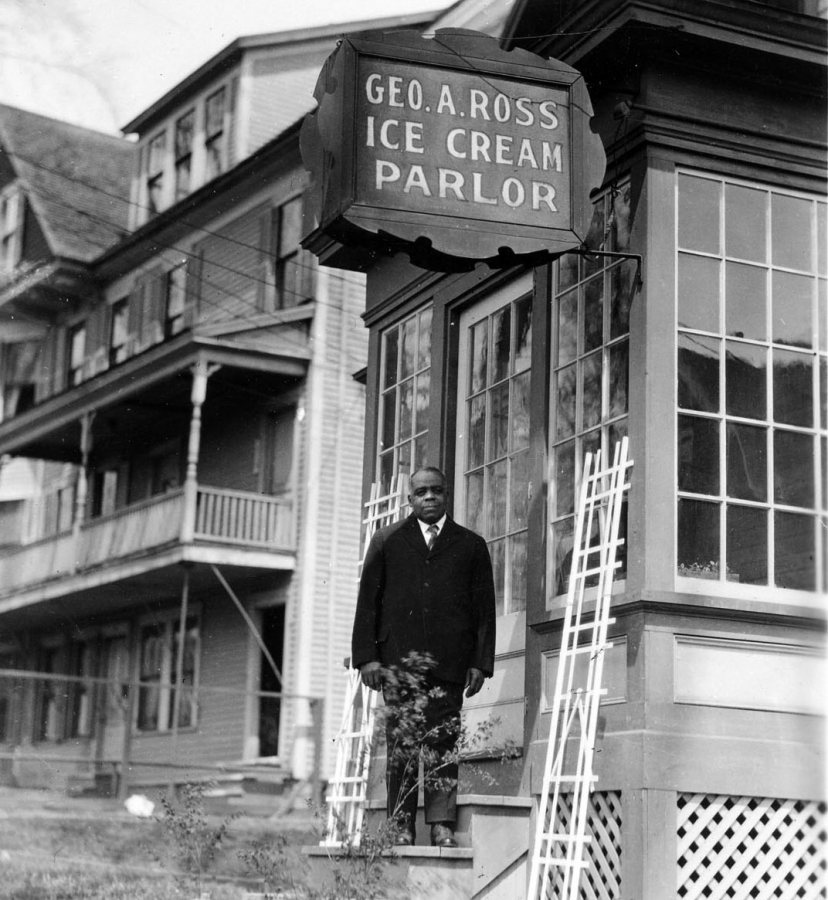

When the quarantine was lifted, in late October, two popular hangouts for students, the Quality Shop and the George Ross ice cream shop, “had a sudden boom in trade.” “The Qual” was at 145 College St., now Lewiston Variety. George Ross, Class of 1904, ran the famed ice cream parlor just west of campus on Elm Street.

When the 1918 campus quarantine was lifted, students flocked to their favorite off-campus spots, including the ice cream parlor run by George Ross, Class of 1904, on Elm Street. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“No one who was not helping in the crisis could realize the difficulties,” wrote Chase in his president’s report. “We shall never cease to be thankful that our ranks were not broken.”

“The quarantine has worked hardships on civilians and soldiers alike but results have been obtained,” the Student reported.

1923: “At a standstill’‘

Less well-known was a college-wide scarlet fever quarantine that lasted most of February 1923.

“College activities at a standstill,” headlined the Student, noting postponement of Winter Carnival as well as exams.

In the spirit of keeping the presses rolling, the paper published its Feb. 9 edition by means of telephone and mail correspondence with the local printer. Though students were not permitted to send letters home (lest they carry the strep bacteria), the editors promised that they did not violate the “safe and sane regulations” that had been imposed: “All copy, before passing through the mail, has been fumigated.”

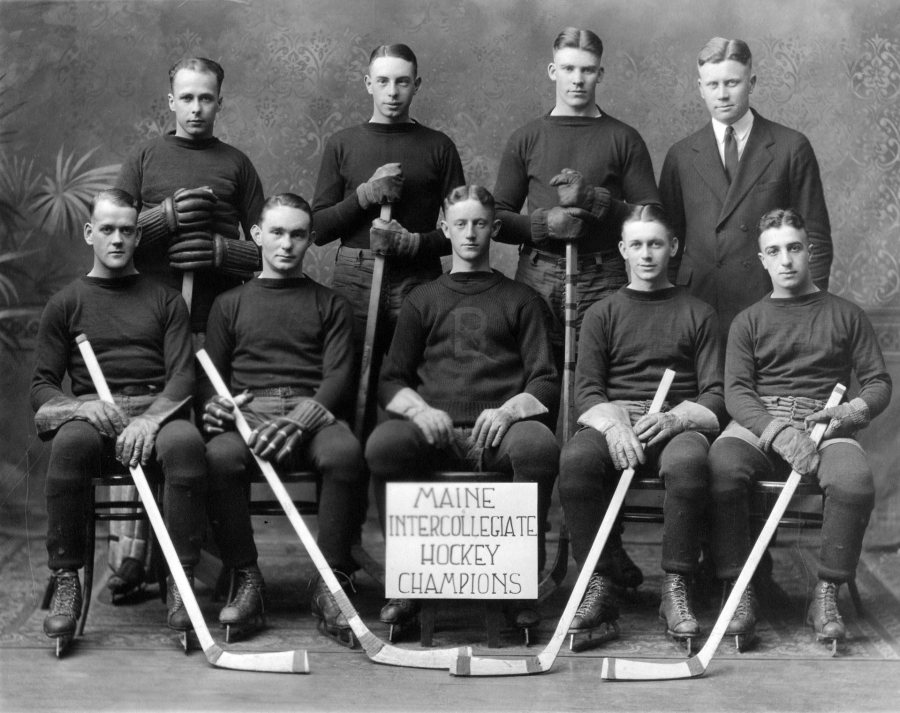

Bates was quarantined for most of February 1923 due to scarlet fever. All activities were halted — except varsity hockey, which won the state championships. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Several students tried to beat the quarantine by leaving for home. They didn’t get far. One was detained in Portsmouth, N.H., and put into solitary quarantine there for seven days.

“It is only to ward off a possible epidemic that the radical measures have been pursued,” the Student promised.

1929: “In cold blood”

Influenza roiled the country again in 1928–29, visiting the campus in January 1929.

In an editorial, the Student took direct aim at sick students who failed to self-isolate, possibly inflicting a mortal sickness on some other poor soul.

“The generous person who would give his all to a starving stranger is just selfish enough to give influenza to a friend whose system may not be able to stand the ravages of sickness,” said the Student. “He who kills this way is no better than the murderer who kills in cold blood.”

1957: “Clueless folly”

In October 1957, various small-college football games in the Northeast were canceled due to the 1957–58 influenza pandemic, including Bowdoin vs. Williams and Colby vs. Trinity.

“Bowdoin, with many flu casualties last week, played Amherst and lost 58-14. If the flu bug had been kind, this would have been a close game. At one time or another, the ‘bug’ affected about half of the 775 Bowdoin students,” reported the Student.

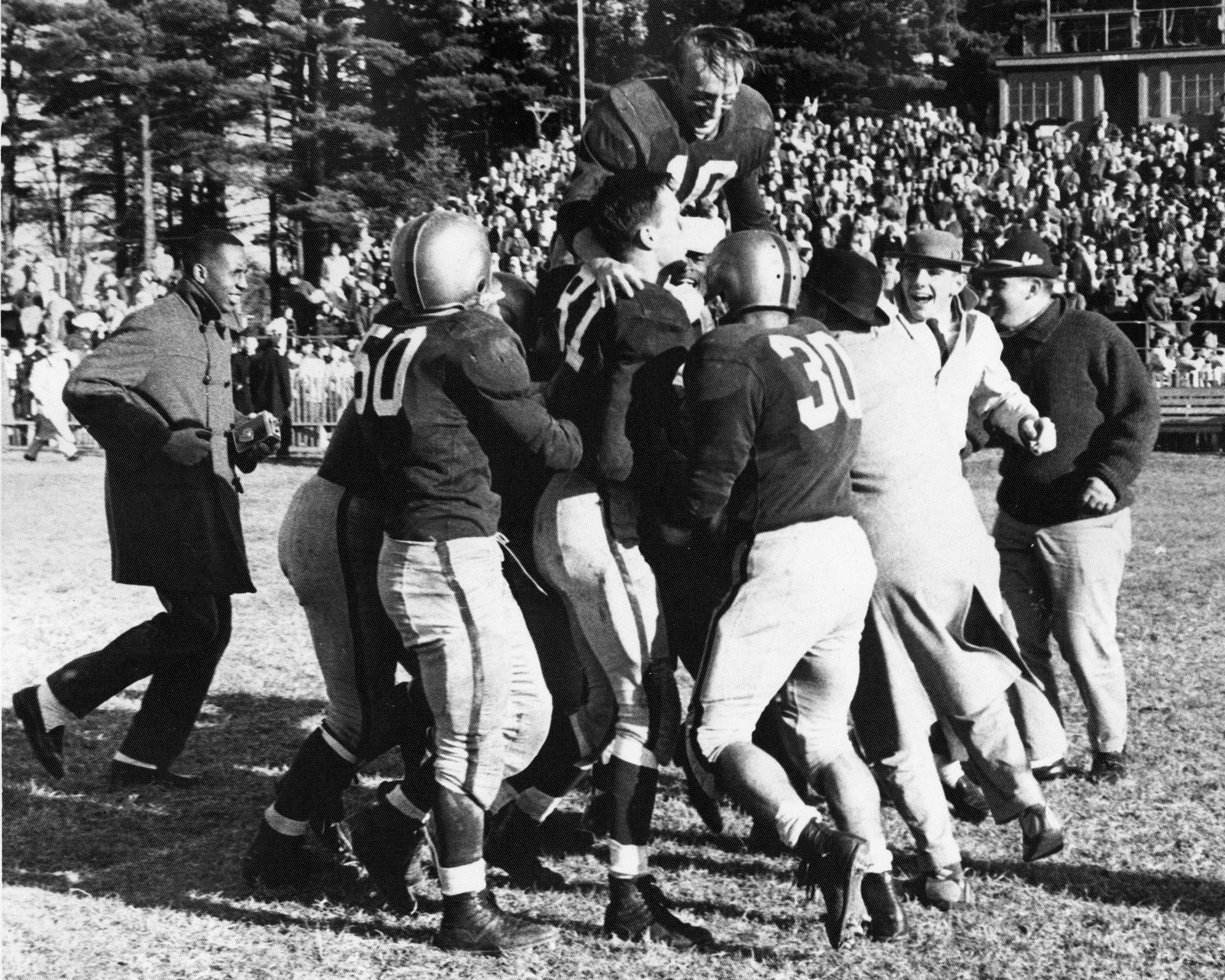

Mostly avoiding the flu, the Bates football team defeated the University of Maine on Oct. 26, 1957. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Bates avoided canceled games, and defeated the University of Maine on Homecoming, Oct. 26.

With about 40 Bates students suffering from flu-like symptoms, Bates physician Dr. Rudolf Haas deflected questions about whether they were afflicted with the specific H2N2 virus known as the Asian flu.

“The symptoms [of various influenzas] are all the same and it is almost impossible to tell the difference,” he told the Student. Haas was chief of staff and president of the medical staff at Central Maine Medical Center as well as the college physician from 1947 to 1973.

Students were reminded that they were “permitted — and even requested — to leave a class if illness or a ‘coughing fit’ should overcome them,” noted the Student.

In a recent essay in City Journal, Clark Whelton ’59 compared his recollections of the pandemic — which he experienced at Bates and which killed some 116,000 Americans — to what’s transpiring now.

“I look back and wonder if an oblivious America faced the 1957 plague with a kind of clueless folly,” writes Whelton, a former mayoral speechwriter in New York City. “In short, why weren’t we more afraid?”

1980s: Bubbling up

Once in common use to describe students’ obliviousness to the world beyond Bates, “Bates Bubble” is less-heard today, perhaps as students and Bates have become more integrated into the Lewiston community.

It’s germaine to note the germinal history of the term “the Bates Bubble.” It was coined in the 1980s by students who were likely aware of (if not still scarred by) the iconic 1970s made-for-TV movie, The Boy in the Plastic Bubble, starring John Travolta as a severely immunodeficient teenager.

2009: All mixed up

The 2009 pandemic of H1N1 or “swine flu” visited Bates in the fall. During the peak of the outbreak, 97 new cases were reported over a two-day period in October.

(During the outbreak, Bates counted those who had “influenza-like illness,” a term that, in lieu of testing, describes illness that may or may not specifically be influenza. After the first three confirmed H1N1 cases, anyone exhibiting symptoms was treated using standard protocols.)

During an H1N1 vaccine clinic in October 2009, Miljan Zecevic ’10 receives his vaccine injection. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

The total number of cases of ILI at Bates topped 280, or about 16 percent of the campus student body.

The sudden spike in cases in October caught the attention of Bates faculty members Meredith Greer (mathematics) and Karen Palin (biology).

In their published research, they found that two large vaccine clinics at Bates, held on Oct. 10 and 15 in Chase Lounge, may have played a part in the spread on campus.

Serving about 1,000 students, the clinics certainly followed social-distancing protocols. But they had an unintended consequence, the researchers believe, by influencing student traffic patterns on campus.

On the days of the clinics, they say, students altered their movements enough that they came into contact not with more students on those days, but with different students. The mingling created what epidemiologists call a “mixing event” — a potent gathering of virus vectors.

(The Air Force Academy also had an H1N1 outbreak in 2009; their mixing event was a July 4 party where new students, basic cadet trainees, socialized with members outside their own squadrons.)

Hosting the clinics may have “facilitat[ed] the spread of H1N1 in unexpected and unknown ways,” the authors say.